Misti Traya enjoys a conversation with the doyenne of food writers…

Clarissa Dickson Wright once likened taking a call from Elizabeth David to “answering the phone to God.” Prue Leith, who won David’s kitchen table at auction, also compared her to the celestial. “I used to take her en primeur vegetables. It felt like an offering to a goddess.” Considering this, it is not unreasonable to liken David’s writings to The Book of Common Prayer. Her recipes and writings are our liturgy. If we follow them, we bask in her grace.

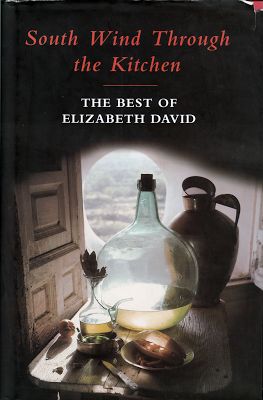

The first time I read one of David’s books, I was nine weeks pregnant and on holiday in the Languedoc. One morning, between bouts of being ill, I found a copy of South Wind Through the Kitchen: The Best of Elizabeth David in the house library. At first glance, it appeared to be nothing more than the posthumously published greatest hits of a writer that I, as an American, did not know. After devouring it, I realized it’s a touching eulogy compiled by those who loved her. Each piece was selected by someone close to David. Most contributors included a personal post script.

From page one, I felt like I had entered conversation with a friend. Though I now know many food writers have likened Mrs. David to the divine, at the time I didn’t have any preconceived notions. I found her accessible, human, and wry. Her prose entertained me and her loved ones’ anecdotes endeared her to me. I also identified with her as she wrote about the same thing I did since leaving Los Angeles for London five years ago – flavours from faraway shores. Elizabeth David was no distant goddess; she was a kindred spirit.

Many food writers begin their careers when they leave the land of their birth. For Mrs. David, it was not leaving home but returning to it that inspired her. From 1939 to 1945, she lived in Marseille, Antibes, Corsica, Sicily, Yugoslavia, Athens, Cairo, and Delhi. When she returned to England, she was greeted with grey skies and food rations. Imagine her horror at having to trade fresh fish and ripe mango for SPAM and powdered eggs. No wonder she chose to ruminate on the flavours of years past.

South Wind Through the Kitchen is a surprisingly emotional read and not just in your first trimester. While it contains recipes from France, The Mediterranean, and The Levant, the book is really a collection of Mrs. David’s memories of those places. When she was first published in 1950, the transportive quality of her prose took readers out of dreary post-War London and deposited them on sunny sands. Today, her words still resonate. In deepest winter if I can’t find my way back to the warm shores of the West Coast, I read her essays with a cup of hot tea and immediately my insides begin to thaw.

Mrs. David née Gwynne was the daughter of landed gentry and attended many a debutante ball where it was assumed she would meet a husband, if not the man of her dreams. When this didn’t happen, she spent a year abroad that changed her life. In the 1930s whilst studying history and literature in Paris, young David lived with a food conscious family that loved to cook. Upon returning to England, she wrote “forgotten were the Sorbonne professors and the yards of Racine learnt by heart . . . what had stuck was the taste for a kind of food quite ideally unlike anything I had known before. Ever since I have been trying to catch up with those lost days when perhaps I should have been profitably employed watching Leontine in her kitchen.”

The title South Wind Through the Kitchen came from an essay David published in 1964. It is a reference to South Wind, a novel by her much loved friend, Norman Douglas. He reinforced what Leontine practiced and instilled in David an appreciation for simplicity that is omnipresent in her writing. “Good cooking is honest, sincere and simple and by this I do not mean to imply that you will find in this, or indeed in any other book the secret of turning out first class food in a few minutes with no trouble. Good food is always a trouble and its preparation should be regarded as a labour of love.” I think of this whenever I eat her daube de boeuf provençale. Lucky for me, it is a dish my husband loves to cook and yes, it makes me feel loved.

Docteur Édouard de Pomiane was another hero of David’s who championed simple food. He invented gastrotechnology and was known for his disdain of haute cuisine. David wrote about him in an essay called Pomiane, Master of the Unsacrosanct. This piece includes a recipe for Tomates à la Crème, a dish de Pomiane credited to his Polish mother despite the French name. Only three ingredients are required: butter, tomatoes, and thick cream. It’s laughably simple. A child could make it. Yet the marriage of these basic flavours yields a dish that is equal parts sophisticated and subtle. Therein lies the magic Mrs. David prized.

About her love for De Pomiane, David wrote, “This is the best kind of cookery writing. It is courageous, courteous, adult. It is creative in the true sense of that ill-used word, creative because it invites the reader to use his own critical and inventive facilities, sends him out to make discoveries, form his own opinions, observe things for himself, instead of slavishly accepting what the books tell him.” This is just what I love about her.

David found extravagance in wasting nothing. She taught readers how to use everything. Per her suggestion that “Beautifully flavoured pork dripping is a wonderful fat in which to fry bread or little whole potatoes,” my fridge is now full of small ceramic dishes–each one holding a different kind of dripping that I top up like a sherry solera. Even her most decadent desserts like chocolate chinchilla are thrifty. “This is a splendid – and cheap- recipe for using up egg whites left from the making of mayonnaise, béarnaise, or other egg-yolk based sauces.” Despite her upper-class upbringing, David’s ethos was waste not, want not. Especially when it came to drink.

One of David’s most famous pieces, Ladies’ Halves, is about her dissatisfaction with wine waiters and their presumptions about ladies who lunch. Her peeve was that waiters always brought her half-bottles when she really wanted a whole. She comically wrote about about being told off by a steward on a rattling train. “A bottle, madam? A whole bottle? Do you know how large a whole bottle is?” David was the kind of woman who knew exactly how large a whole bottle of chablis was. That’s why she wanted it.

In another wine related anecdote, April Boyes who chose an essay of David’s called Oriental Picnics included a funny story about her friend. “String was a vital part of Elizabeth’s picnic equipment, and so the bottle of wine was lowered into the pool, and attached to the shrub. . . At the end of the morning we returned to the square and set out rugs and cushions, a tablecloth, and then the picnic. Fortunately the wine was still in place, nicely chilled.” I like to think Ms. Boyes continued David’s tradition of taking string on picnics in memory of her friend. Even if she didn’t, I do.

Sometimes, for some people, food and memory blur. When this happens feelings can develop flavours. Sabrina Harcourt-Smith recalled an afternoon at her Aunt Liza’s in the early 1960s. “She was preparing scallops with butter and breadcrumbs on her large kitchen table. These were the Coquilles St. Jacques à la Bretonne which she had recently described in the shellfish chapter of French Provincial Cooking. As she arranged the scallops in their shells, her little black cat sat on the table and patted her arm impatiently until she said, ‘oh all right, Squeaker,’ and indulgently gave her one scallop, followed by another.” When I read this I wondered if scallops always reminded Ms. Harcourt-Smith of Squeaker and Aunt Liza much the way cinnamon toast reminds me of the first day of school. My mother always made cinnamon toast for me at the start of the school year. This year I found myself doing the same for my daughter.

Not only did David share her best recipes with her readers, but she also introduced them to colourful characters they may have otherwise never met. Among the brightest was Colonel Kenney-Herbert, an officer in the Madras Cavalry, who wrote about cooking and living under the Raj in British India during the 1890s. Upon returning to England, he opened a cooking school on Sloane Street. Other favourites include David’s Greek friends, Christo and Yannaki, who were her neighbours when she lived in the Aegean. They loved “picklies” (piccalilli) and Christmas cake which she made for them in exchange for fresh fruit, vegetables, and the use of their donkey for transportation.

Part of what makes David’s tales so intriguing is not just the delicious food she consumes or the vibrant characters, but the way she sets the stage. She had the eye of an art historian and could describe venues like Old Master paintings. Of the dawn’s early light on the Venetian fishmongers’ stalls she wrote:

It makes every separate vegetable and fruit and fish luminous with a life of its own, with unnaturally heightened colours and clear stencilled outlines. Here the cabbages are cobalt blue, the beetroots deep rose, the lettuces clear pure green, sharp as glass.

On 20 May 1992, David suffered a massive stroke. She died two days later early in the morning, having enjoyed a good bottle of chablis and some caviar brought to her by friends. She was seventy-eight years old. On 28 May, she was buried at her family church, St. Peter ad Vincula in Folkington. As tribute to her, someone placed a loaf of bread and a brown paper bag of herbs amongst the lilies, blue irises, and violets at her funeral. In September of that year, a memorial service was held for her at St. Martin-in-the-Fields. Across the street, there is a portrait of her by John Stanton Ward in the National Portrait Gallery. Mrs. David’s service was fittingly followed by a memorial picnic in the Nash Room at the Institute of Contemporary Arts. I like to think that even though the bottles of wine were in ice buckets somebody still brought string. Elizabeth David said “There are people who take the heart out of you, and there are people who put it back.” For post-war Britain and this American ex-pat, Mrs. David did and does just that.

That was a great read! I too have spent many a happy winter’s evening tucked up in bed with the wind howling outside reading ‘Italian Food’ and ‘French Provincial Cooking’ and imagining the sunshine! As well as being sparing with her ingredients list, she also had a good mid-century-style frugality with words, which I have always admired

Adam Gopnik wrote*:

“There are two schools of good writing about food: the mock epic and the mystical microcosmic. The mock epic A. J. Liebling[**], Calvin Trillin, the French writer Robert Courtine, and any good restaurant critic) is essentially comic and treats the small ambitions of the greedy eater as though they were big and noble, spoofing the idea of the heroic while raising the minor subject to at least temporary greatness. The mystical microcosmic, of which Elizabeth David and M. F. K. Fisher are the masters, is essentially poetic, and turns every remembered recipe into a meditation on hunger and the transience of its fulfillment.

“The two styles can’t be mixed. If we are reading, say, about Liebling’s quest for the secret of how rascasse are used in bouillabaisse, we don’t want to be stopped to consider the melancholy lives of the remote fishermen who seek them out. And if we are reading David’s or Fisher’s sad thoughts on the love that got away on the plate that time forgot, we would hate to find, on the next page, the writer handing out peppy stars in modish kitchens. (The same thing is true of sportswriting: we go to it for either W. C. Heinz’s tears or Jim Murray’s jokes, Gary Smith’s epics or Roy Blount, Jr.’s yarns, which suggests that, with the minor arts, our approach is classical and depends on unity of tone.)”

Some of us might just coincidentally be in the midst of reading A. J. Liebling’s ‘Between Meals’ and wondering skeptically whether Elizabeth David’s writing might be our cup of tea. We might even have some of Liebling’s and Trillin’s books on our shelves but not any of David’s and Fisher’s. Is it because most readers of food writing might be divided into two schools as well: those who enjoy the comic more than the mystical and those the mystical more than the comic? Or maybe the division is those who enjoy mainly or only eating and those who enjoy both eating and cooking? (I’m wondering only about whether most readers might be so divided. I have no doubt there are some readers who contain multitudes and enjoy both schools of writing equally.)

================================

* http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2005/04/04/dining-out-3

** http://thedabbler.co.uk/2012/05/greens-heroes-of-slang-16-a-j-liebling/