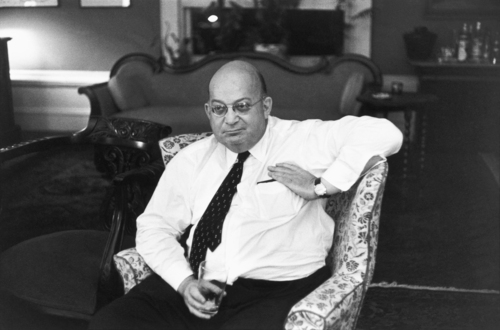

Today’s hero of slang is “a literary, literate fat man” who loved food and French girls’ legs…

I can write better than anybody who can write faster than me;

and I can write faster than anybody who can write better than me.

He should have lived hereafter, but instead, born in that annus mirabilis of 1904 (too young for the first one, too old for the second) he was gone in 1963 when Muhammad Ali – what a match-up that would have made – could still be called Cassius Clay. He was a literary, literate fat man, like Samuel Johnson and Cyril Connolly and in his case the surplus poundage saw him off. He was a Jew – far from self-hating but simply self-ignoring (and was there ever man less willing to submit himself to the laws of kashrut?) – who wrote for the arch-WASP New Yorker, an American never happier than in Paris, a pampered Ivy League drop-out (expelled, actually, when he preferred lie-ins to chapel) who found himself writing the best boxing coverage since his own hero Pearce Egan, and – one incongruity further – covering US troops in World War II, a conflict whose quartermasters were unable to find him a sufficiently capacious uniform. His love-life – there was a schizophrenic wife, though he allegedly found a final four years’ happiness elsewhere – floundered, and he wrote lyrically of French girls’ legs. He also wrote of Broadway, of its old-timers, its conmen and its strugglers, and of the food of every menu – and there seemed an endless supply – that he came to sample.

Food was so important, and he sympathetically noted the sparse commons meted out to pugs on their managers’ orders. For himself he preferred excess. He had, so he claimed, tricked his father into sending him to Paris in 1926 by inventing a forthcoming marriage to an ageing, possibly pregnant widow. He was given $200 a month – not vast but the exchange rate was remarkably kind – and spent a year of bliss. He made sporadic appearances at the Sorbonne, walked the right bank streets (‘I was often alone but seldom lonely’) – Hemingway and Co. were self-aggrandizing across the river but Liebling was too young for that fast company and, though he never set fiction to platen, dare I suggest a far superior artist than them all. Mainly he ate, and remembered it all in the wonderful Between Meals, which concentration of the primacy of knife and fork indicates the man’s priorities. (A small sample can be found at http://nyti.ms/K6sTCR). When he returned in 1944 the great yet cheap restaurants that had informed his palate were gone and he mourned them even as he celebrated Liberation.

Food impinged on other worlds. Thus his assessment of Proust, that consumer of madeleines: ‘In the light of what Proust wrote with so mild a stimulus, it is the world’s loss that he did not have a heartier appetite. On a dozen Gardiner’s Island oysters, a bowl of clam chowder, a peck of steamers, some bay scallops, three sautéed soft-shelled crabs, a few ears of fresh picked corn, a thin swordfish steak of generous area, a pair of lobsters, and a Long Island Duck, he might have written a masterpiece.’

Back in New York he tried for a job on Pulitzer’s New York World, which involved hiring a sandwich-man to parade a sign demanding ‘Hire Joe Liebling’. The job came, though through other, simpler methods, and lasted until the paper was gobbled up. Meanwhile Liebling began perfecting his art, which in 1935 took him to the New Yorker. Here, along with his friend Joe Mitchell, another newspaperman and another still worth reading, he produced pieces that transmuted love for and knowledge of the city into would now be termed the higher journalism. The ‘new journalism’ would wait 30 years for its christening, but Liebling and Mitchell were surely its chief progenitors. For 28 years at the magazine he wrote fast, high and wide, and above all with enjoyment; passers by his room would see him chortling with pleasure as he pulled successive sheets from the typewriter.

Unlike Mencken, an older contemporary and another glorious prose stylist (and trencherman), Liebling is rarely if ever cruel. He prefers the subtle implications of irony to Mencken’s brimstone savagery. His topics drew on what his hero Egan would have termed the ‘sporting’ world, which as well as actual sportsmen – jockeys, prizefighters, the ancillary world of both – meant that of gamblers and chancers of every hue, of criminals (mainly minor) and above all of those who, legitimately or otherwise, struggled to make a buck. His greatest creation – though the man was of flesh-and-blood, real name James A. Macdonald – appeared in The Honest Rainmaker, subtitled ‘The Life and Times of Colonel John R Stingo’. Stingo was a racing tipster who lived in what he called a ‘one-room suite’ above a mid-town bus terminal. His life, at least as conveyed by Liebling, was an epic of tricksterdom, profitable or not. Self-promoters – to be kind – were always Liebling’s stock in trade: he wrote about Huey’s Long’s even more outrageous brother Earl, who would follow as governor of Louisiana, and of Father Divine, one of those preachers whose reputation varied between God (his own assessment) and a money-grabbing charlatan (that of those who had resisted his sermons). Lower down the scale he wrote of the ‘Telephone Booth Indians’, the hustlers whose ‘offices’ were the public phone booths of the Brill Building, now gone, later the home of such as Lieber and Stoller, but then a warren of hire-by-the-day offices and home to show business’ lowest forms. He wrote regular commentaries on the US press, of which he was both an acute analyst, watching with sorrow as its power declined in the face of new media, and one who appreciated the entertainment value – intended or otherwise – of those who owned and conducted it.

Above all, and the area for which he remains most celebrated, there was the boxing, memorialized in two collections: The Sweet Science (which phrase he believed was an Egan coinage but was more likely created by Egan’s rival John Badcock) and A Neutral Corner. His fight reports and trips to training camps, to Lou Stillman of the world-famous 47th Street Gym, to the cut-man Whitey Bimstein or to Jacobs’ Beach (the world of Madison Square garden super-promoter Mike Jacobs) are his own version of Egan’s 1820s chronicle Boxiana. He slips seamlessly from referencing the past to itemising the present, laying out the story of a sport that seems to flow unbroken from Mendoza to Tom Sayers to Jack Johnson to Rocky Marciano. Given the hegemony of the contemporary Mob over US boxing, some termed Liebling, who at least wrote as if he took all at face value, naïve. He was not, one must admit, judgmental.

What point these comments? Only as a signpost. I could quote, but there is no space and in any case Liebling demands personal interrogation. There are important others, I tip my hat to Joe Mitchell again, but there are none better. For a real assessment neither excerpt nor quote will do. The books, or most of them, are available. What, pray, is stopping you?

Love the parallels with today of the journalists of the 1930’s struggling against the ‘new media’ of tv and radio diminishing their livelihoods

I bet there would be a decent film script in the travails of the Brill Building ‘Indians’ too…

There would be roles for such as Hy Sky, the sign painter Judge Horumph (who prefers not to enunciate his name, and is no judge), Marty the Clutch (from his ultra-firm handshake), Lotsandlots the property developer, Hotticket Charlie the tout, and many more. Liebling called it the Jollity Building but I think tears vied with laffs. My favourite inmate is Maxwell C. Bimburg, self-styled ‘Count de Pennies’, of whom it was noted during a brief period of prosperity that ‘it must have been a terrible temptation to him to stay honest, but he resisted it.’

brilliant! So…c’mon Martin Scorsese ! It’s practically written itself!

I wish I knew where my old copy of Between Meals went–lent out, I suppose, and never returned. Liebling certainly had an ear for colloquial speech, yet I don’t think of him as using great quantities of slang. His work is easier to find than it was 30 years ago.

You are wholly correct, although once one goes looking there is always (a little) more than one had originally noticed. The reality is that I included him for his heroic status rather than for his slang one.

While on the topic of New Yorker writers: have you included or considered including S.J. Perelman?