2015 marks the 150th birthdays of two great Scandinavian composers. The concert halls will accordingly be awash with the more famous works of Jean Sibelius and Carl Nielsen, but today Mahlerman treats us to some of their less well-known gems…

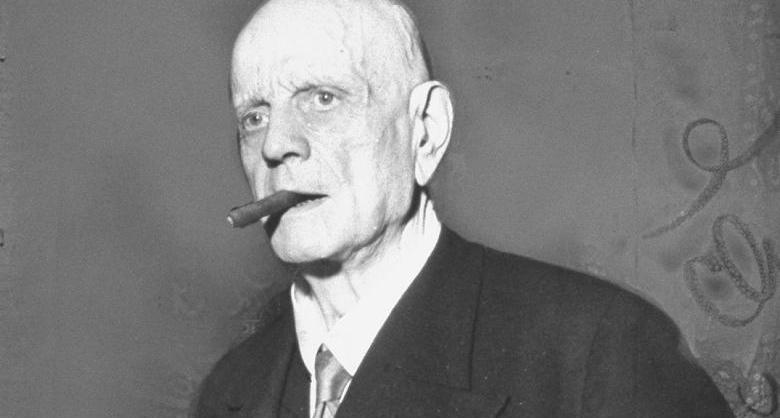

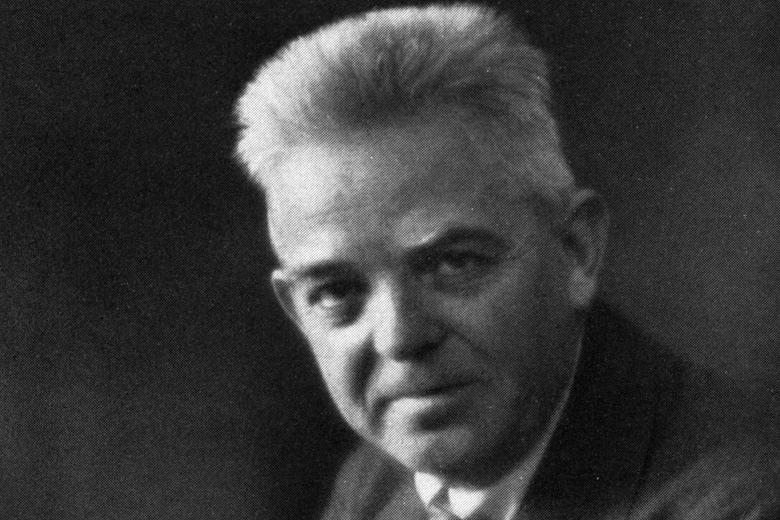

The year 1865 turned out to be quite an important one on the stage of the musical world, as a clutch of composers arrived ‘mewling and puking’, some, ‘in the nurse’s arms’, others, less fortunate, into the arms of probably a family member or close friend. Alberic Magnard and Paul Dukas were both Parisian, Alexander Glazunov from St Petersburg, and all three, though artists of the second rank, have featured in these pages over the years. However today we are concerned with the first rank, and 150 years ago two babies first saw the light of day, six months and one thousand kilometres apart, in Scandinavia’s frozen north, Jean Sibelius [above] to an affluent professional family in Finland, Carl Nielsen [below] into peasantry on the Danish island of Funen.

Although we rightly think of Sibelius as one of the 20th Century giants of symphonic music, he was plagued with doubts about his stature as a creative artist for most of his long and often chaotic life, spanning 91 years and fuelled, as it was, by alcohol and depression. Could it have been during one of these frequent periods of self-doubt that he said to Nielsen, during one of their frequent meetings, that ‘I don’t reach as high as your ankles’ ? Could it have been that the Finn recognised the ‘human spirit’ that percolates through almost everything that Nielsen wrote, and the almost total absence of it in his own compositions hewn, as they seem to be, out of the very tundra (tunturia in Finnish)?

The birthdays of these two (yes, two) giants will, unfortunately, be seized-upon by concert promoters to offer us yet more cycles of the Sibelius symphonies, along with the 4th and 5th of Nielsen. Today, at the start of their anniversary year, and this being The Dabbler blog, I thought we might broaden the canvas, and tread the overgrown path where riches are to be found for those with ears to hear.

It is a mystery to this writer that Nielsen’s Symphony No 3 ‘Sinfonia espansiva’ is heard so rarely, imbued as it is with all the vigour (and serenity) of being alive – the composer described it as ‘a gust of energy and life-affirmation blown out into the wide world’. I find the serene second movement Andante pastorale as bewitching as almost anything in music, shot-through with the ‘idyllic and heavenly in nature’. A masterstroke surely, to introduce, toward the end, a wordless chant (of ‘ah’) from first a baritonal man, followed by a woman’s soprano, here, again, best described by the composer: It depicts

peace and calm in nature, interrupted only by the voices of a few birds, or what you will……towards the end the rural calm and depth grows rather more concentrated, and from afar off one hears human voices; first a man’s and later a woman’s voice, which once more disappear, and the movement ends in entirely unemotional calm (trance).

Although the Paducah Symphony Orchestra (Kentucky,US) conducted by Raffaele Ponti display a few rough patches, the idiomatic calm of the whole is beautifully captured here, I feel.

Nielsen, a late starter, was already in his mid-forties when he completed the Third Symphony, his opus 27, in 1911. By this date Sibelius had completed twice that number, his searing A minor symphony carrying the opus number 63. At this time the composer was suffering under one of the many periods of depression that, from time to time enveloped him and, as you might expect, his mood is reflected in both the symphony, and the short tone-poem The Bard, that was composed concurrently with it – and although the orchestra is large, the use of it is remarkably restrained throughout, opening and closing with a harp obbligato, but retaining Sibelius’ trademark atmospheric concentration; the sadness is unrelieved. I was lucky enough to hear the late Paavo Berglund conduct Sibelius many times, and I don’t expect to hear his like again in this music; here, he could be conducting the Finnish RSO but, in fact, it is the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra. Enough said?

Most composers of note inscribe their opus one during their teenage years, but Nielsen was well into his twenties when the three-movement Little Suite appeared in 1888. Slight though it is, it reveals a level of accomplishment that the composer had already developed whilst writing as a student for string quartet, and the central Intermezzo, played here by members of the Norwegian Chamber Orchestra is a piece of great charm in Nielsen’s favourite triple-time, with muted strings illustrating the composer’s craftsmanship in every bar.

In 1896 Sibelius, not for the first or last time, suffered a profound creative crisis. His attempt to compose a Wagnerian music drama (Veneen luominen) had foundered, and he was anxious not to waste what he viewed as some worthwhile material. The result of this trawl was refashioned into the Four Legends from the Kalevala, or Lemminkainen Suite, and published as his opus 22 (with later revisions). Although just into his thirties, the composer’s sense of mood, colour and sonority is singular here, and the sense of organic growth throughout the four movements is a marker for the symphonies that would follow these ‘tone poems’. Here, to end today, is the haunting second movement, The Swan of Tuonela. Muted strings again, with the swan represented by a plaintive Cor Anglais (pitched a fifth lower than an oboe), floating across the landscape and eventually fading over a quietly beating drum (tam-tam), with the strings creating an icy chill by playing tremolos with the wood of their bows. Bleak and magnificent. The images with this video are by the Majorcan photo-journalist Pep Bonet, and require no comment from me.

Sibelius is my favourite composer and I also love Nielsen, so I’m looking forward to the various concerts and broadcasts this year. The Bard is an exceptional piece and I’ve loved the Expansiva ever since I bought the Ole Schmidt Unicorn recording.

If the supposed fragments of the 8th symphony on YouTube are anything to go by, he was about to embark on a new phase in his development. It’s tragic that self-doubt led Sibelius to burn the full score. Have you heard the theory that the late organ piece ‘Funeral’ is actually a movement from the symphony?

I share the sadness that we never heard the Eighth Symphony. After reading your post, MM, I turned to Erik Tawaststjerna’s biography of Sibelius (translated by Robert Layton) to remind myself of his thoughts on the matter. He puts forward the following:

‘Why did it all end this way?The evidence would seem to point to the fact that his self-criticism had gained the upper hand and had become totally destructive. He had after all composed four great works during 1923-6, and there is nothing to suggest that his mental faculties were in any way diminished. One thinks of his youth, when he consulted an ear specialist and learned that in the course of time he would become completely deaf. He reacted strongly at the time in a letter to Aino: ‘A musician who cannot hear. Now I shall ensure that I listen to orchestral music above all else as long as I can still hear; then later, when the hearing has gone, one will be able to imagine the sound better…..Do not tell anyone of this. I simply cannot bear the thought of people saying it sounds like that because he is deaf.’ Perhaps a factor in his reluctance to release the Eighth Symphony was that he could not bear the thought of people saying: ‘It sounds like that because he is old.’

‘After his death, Aino Sibelius told me: ‘In the 1940s there was a great auto da fe at Ainola. My husband had collected a number of manuscripts in a laundry basket and burned them on the open fire in the dining room. Parts of the Karelia Suite were destroyed – I later saw remains of the pages which had been torn out – and many other things. I did not have the strength to be present and left the room. I therefore do not know what he threw on to the fire. But after this my husband became calmer and gradually lighter in mood. It was a happy time.’

In his English-language book on Sibelius, the composer’s secretary Santeri Levas wrote: ‘In August 1945 he told me that he had destroyed the whole work. “My Eighth Symphony” he said, “has been ‘ready’ – ready in inverted commas – many times. I even went so far as to put it in the fire.”’

It all seems inconclusive. Perhaps the old chap was playing with his and future generations, leaving just enough clues for someone, one day, to work it out. Perhaps there’s still hope.

A preferred way, for me, of listening to a particular part of Sibelius is to go walking before sunrise in Winter on very cold frosty mornings with a clear starlit sky and, through earphones, listen, enthralled, to the second movement of the Third Symphony. Talk about communing with Nature! Magical!

My preference, overall, is for Sibelius over Nielsen, but, my goodness, there’s not a lot in it! I love them both.