The famous Chesapeake oyster industry has a strange and violent history, finds Rita…

It was like slurping up a gob of phlegm. I swallowed as quickly as possible to get the awful thing out of my mouth. But then the flavor hit, delicate with a hint of brine. Absolutely delicious.

My first taste of a raw oyster, or as Marylanders on the Eastern Shore say, orster. My husband, descended from a long line of Chesapeake Bay watermen, had insisted I try the regional delicacy at least once. Though oysters are also a traditional London food I had never had one. That first taste cured me of any reluctance based on the phlegmy texture. Now I bite into the squishy things with relish.

In fact I might have turned into a bit of an oyster connoisseur, even a snob. When we order raw oysters we question the waiter as though we are ordering fine wine. Sweet or briney? From the Chesapeake’s Maryland or Virginia waters? (Of course there is a rivalry, of which more later). The varieties even have creative names and pretentious descriptions just like wines: Chesapeake Golds, Skinny Dipper, Choptank Sweets, and, I swear this is true, Sweet Jesus. The latter have “a clean, sweet taste that’s reminiscent of cucumber with light hints of salt,” according to Baltimore magazine. The other day we were sampling some Holy Grails, “their initial saline burst finishes up smooth and slightly buttery,” when my husband casually mentioned the Chesapeake Oyster Wars as though they were common knowledge, like the Civil War. He grew up hearing the tales of his Crisfield ancestors but the rest of us drew a blank on this historical episode. I had to learn more.

Turns out the Oyster Wars lasted for centuries in one form or another with a particularly bad time in the 1880’s known as the Wild West of the Chesapeake. It all started in Colonial times with the drawing of the Maryland-Virginia border. Charles I’s 1632 charter granting Maryland to Cecil Calvert drew a straight border line from the mouth of the Great Wicomico River to the Pokomoke River on the other side of the bay. Watermen were limited to their own side of the line, but naturally each believed the richest oyster beds and crab fishing waters lay on the other’s side. So the border was immediately challenged with the watermen of the colonial era constantly ignoring the line, often leading to violent confrontations.

By 1785 the situation was so out of control that it even got George Washington’s attention. He convened a group of Maryland and Virginia officials at his Mount Vernon estate. Maybe George tipped the balance in favor of his home state for they drew a new line giving Virginia an extra 20,000 acres. Virginia had the upper hand again almost a century later when more disputes led to the Arbitration of 1877 giving away even more of Maryland’s waters. Now the line zigzagged and meandered about, even slicing through Smith Island. One of the island residents, Johnson Evans, must have known people in high places because he managed to get a 320 foot adjustment that placed his store in Virginia and his home in Maryland. Now he had the right to tong for oysters on both sides of the line.

The border conflict continued well into the twentieth century with the Virginia Marine Police, originally founded in 1875 as the Oyster Navy, chasing errant Maryland watermen back over the state line. Both sides were armed with rifles and there was often bloodshed. In a notorious case in 1900 police shot dead a teenage boy from Smith Island as he fled across the line. But often it was the police who fled the scene when confronted with armed and angry watermen, some of whom might be their own relatives. “On the Chesapeake, sometimes water is thicker than blood,” wrote Christopher White in Skipjack, a history of the watermen and their unique sailboats. “Juney” Crockett, the legendary head of the Virginia Marine Police in the 1980’s recalled:

When I first took this job I had to deal with my own family. I’ve wrote tickets for my first cousin, for my four brothers. I’ve wrote tickets for ’em all. If you can’t do that, you might just as well forget this kind of work.

But even fiercer than the border war was the war that broke out between the traditional oyster hand tongers and the new-fangled dredgers. The invention caused as much havoc on the water as the cotton gin and the spinning jenny caused on land. For generations watermen had used hand tongs, literally giant sized kitchen tongs, and hauled up the oysters by hand. The new dredgers could haul up much larger loads from deeper water. But the dredgers didn’t confine themselves to the deep water; they began encroaching on the shallow waters in the river mouths preferred by the tongers.

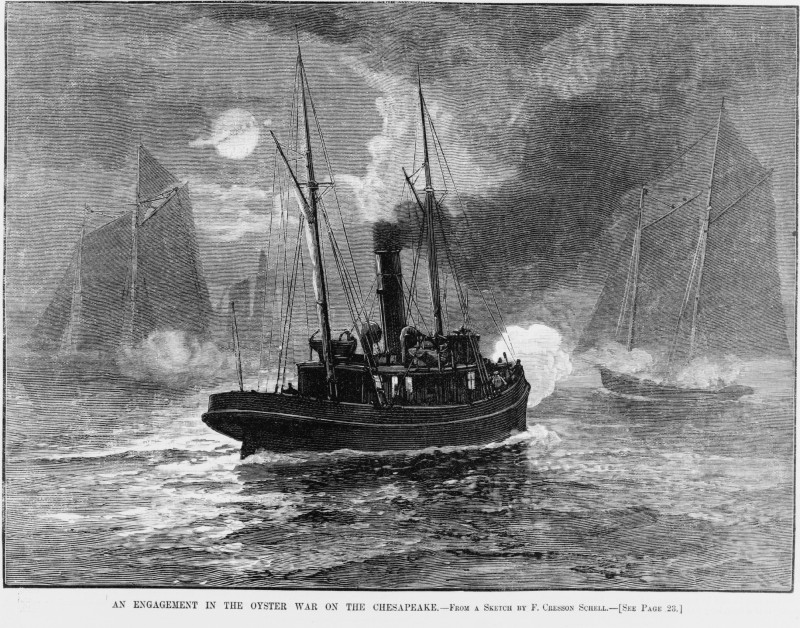

In 1865 Maryland tried to legislate the problem away, passing a law that reserved the rivers for tongers and the bay waters for dredgers. It didn’t work. The decades after the Civil War were the lawless era known as the Chesapeake’s Wild West in both Maryland and Virginia. In one notorious episode in 1879 forty dredging boats entered the mouth of the Rappahannock. The tongers tried to drive them out but the dredgers opened fire. For weeks they kept the tongers away with gunfire. Finally the Virginia legislature decided to supply the tongers with rifles and ammunition so they could defend their territory and their livelihoods, essentially government sanctioned warfare. With bullets flying over the water the Oyster Navy had far more trouble on its hands than just the border conflict. The Governor of Virginia during the 1880’s, William E. Cameron, even got involved, personally leading an assault on the illegal dredgers. He owed his maritime experience to a youth spent working on a Missouri steamboat alongside Mark Twain.

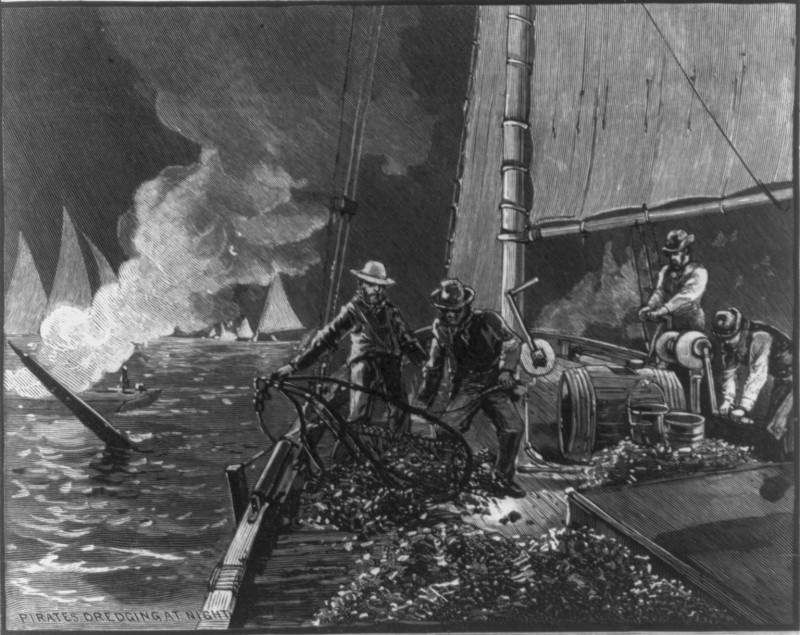

Over in Maryland the mouth of the Choptank with its prime oyster beds was a flash point. Pirate oyster dredgers would invade the river under cover of fog or darkness. The men wore all black, coated their sails with mud for camouflage, and covered up their boat names to avoid detection. They posted sentinel boats to warn of police boat sightings and even dragged the state oyster buoys to change the borders between dredger and tonger territory.

Some of these pirate watermen became outlaw celebrities. One of the worst was Gus Rice who plotted the murder of Hunter Davidson, the Commander of the Maryland Oyster Navy. The attempt failed, but Rice remained a menace. He recruited his crew from the Baltimore jail and the homeless drifters who gathered in shore towns like Oxford and Crisfield looking for work. He engaged in frequent shootouts with the Navy, most notably in December 1888 when seventy dredgers battled a police boat armed with a howitzer. Rice tried to ram the police boat with twelve dredgers lashed together with chains, but ultimately, on this day at least, the pirates were outgunned. The tongers on the Chester River got so desperate they mounted two cannon at the river mouth. Rice retaliated by organizing a nighttime raiding party. They found one lone watchman at the cannons and stripped him, forcing him to run naked along the shore to warn his fellow tongers. Like the border wars the pirate activity went on well into the twentieth century, waxing and waning along with the fluctuating price of oysters. And during Prohibition the pirates were well positioned to do a little rum running on the side.

Since learning all this I’ve become quite curious about what exactly my husband’s grandfathers did in the Oyster Wars. But prying that information out of him is proving as difficult as shucking an oyster.

Nice story Rita! Cant eat the slimey things meself

Great stuff, Rita.

I enjoy the frisson of disgust that accompanies the deliciousness of oysters. Also the faint fear of being poisoned.

Ah, the Wild, Wild East. I’m trying to imagine John Wayne starring in a film about this, but can’t decide whether it would work best if he sailed in from over the horizon to save tongers or dredgers.