Today Mahlerman looks at composers who also painted, or painters who also composed…

The overlap and admixture of musical composition and painting was not something I had even considered until, quite recently, I heard a piece of music (thank you Radio 3) by the Lithuanian composer and painter Mikalojus Ciurlionis – but more about him later. Whether it be artists who compose, or composers who paint, there have been many more than the handful that I was aware of – Gershwin, Schoenberg and the New Yorker Morton Feldman. All, by coincidence surely, Jewish.

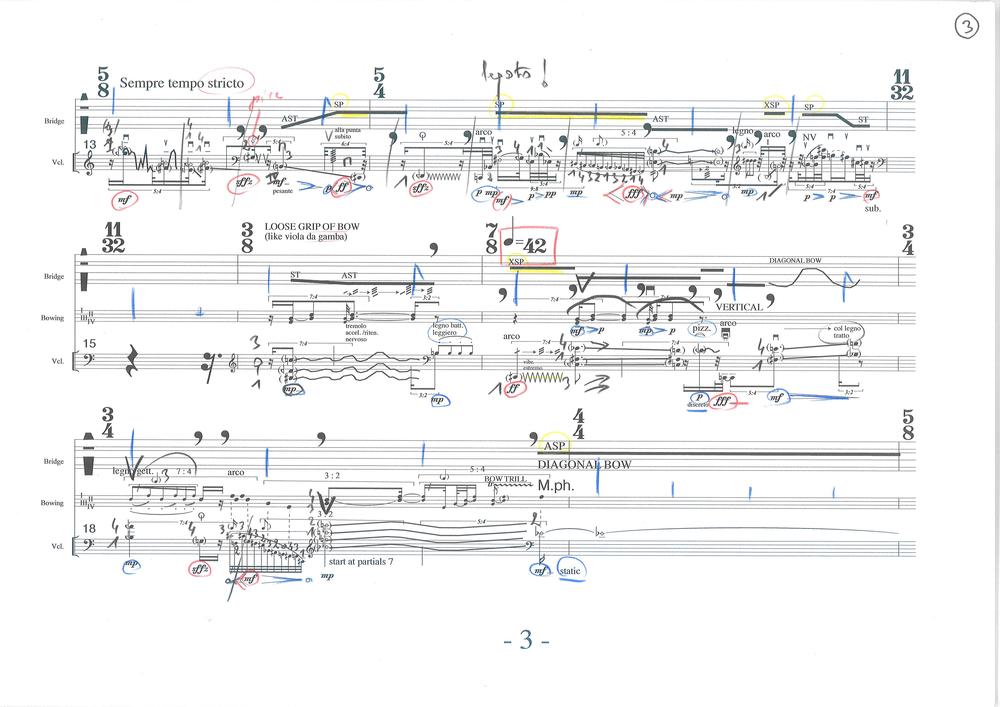

The music of the noisy giant from Queens NY Morton Feldman has been, for the last decade, on a slow upward curve. Glacial and pointillistic, it is hard to grasp that this rumbustious intellectual magician could produce music of such shimmering beauty. Immersed as he was in the artistic world of the1950’s New York avant garde, most of his friends were painters – Jackson Pollock and Philip Guston being perhaps closest to the composer – and in a way that seemed quite natural to him, he developed a ‘painterly’ attitude to the musical scores that he produced, working on a graphic or ‘grid’ system and from time to time, introducing colour to a format that normally stays firmly black & white. The grids don’t make much sense unless you understand them (and I don’t), but put simply they introduce the element of ‘chance’ into the score suggesting, for instance, when you might play a note, but not what that note might be. It seems a bit crazy, but the results are often stunningly beautiful. Here is part of his score for Duration II for ‘cello and piano.

One of his greatest pieces was Piano and String Quartet, composed in 1985, a couple of years before his death. The economy of means here is striking; the repeated upward arpeggio from the piano against the solemn, portentous chords in the strings, producing the hypnotic power that much of Feldman’s music achieved. Hints of Webern, yes – but this is no more than you might expect from this revered master. The painting ‘Bop’, is by the Chicagoan modernist Elizabeth Murray, seemingly from the flower-power era but actually painted early in this century.

Feldman once said of his close friend John Cage that he was ‘…the first composer in the history of music who raised the question by implication that maybe music could be an art form rather than a music form’. Cage held that an artist can work as freely with sound as with paint, and putting aside his experimental work (yes, that famous silent piano piece), he comfortably produced sounds, and rather wonderful pictures, that illustrate this overlapping ‘concept’.

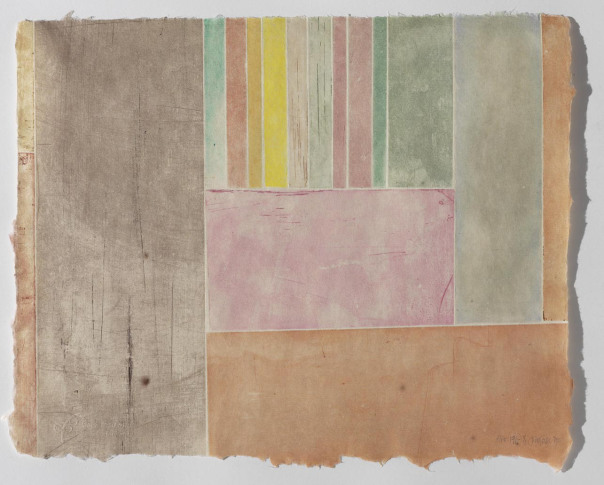

Here is HV2 Number 17b from 1992, an aquatint using 24 plates.

Almost against myself I am often charmed by the music of this quiet revolutionary who, if he did nothing else, helped us all to listen more carefully to the ‘music’ going on around us during every waking moment. We will never know silence, and Cage taught us to accept and appreciate this alarming fact.

Just after WW2 Cage began a deep study of Indian History and Philosophy, and out of this study emerged the twenty small compositions that make up Sonatas and Interludes for prepared piano. Here is No 13.

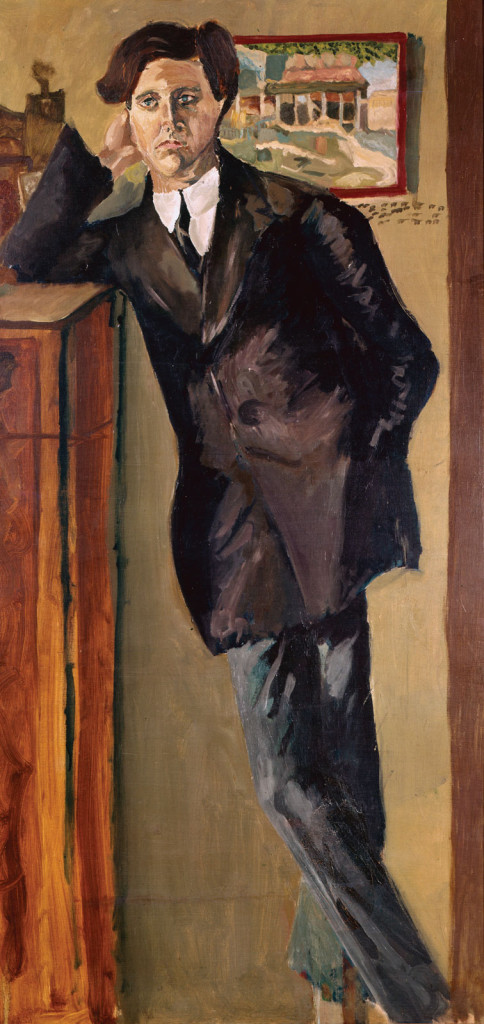

Listening to the early works of Arnold Schoenberg saturated, as they are, with Wagnerian hyper-chromaticism, it is near-impossible to imagine that he would very soon create the alien world of Pierrot Lunaire and, soon after that, give up composition completely for about three years, to devote his life to painting. Does it mean that he wasn’t at one with this challenging ‘new world’? The paintings, particularly the self-portraits, are quite wonderful, as is this embodiment of the composer Alban Berg:

Although the composer insisted he was ‘an amateur’ at painting, his work showed him to be at least the equal of some of the minor German Expressionists of his time, and reminds us also that he was a self-taught ‘amateur’ composer, who didn’t differentiate between his creation of music, and painting. The backdrop for this performance of the last of the Six Pieces Opus 35 for Male Chorus is one of the composer’s haunting self portraits, oil on cardboard, from around 1910.

A little light research tells me that composers we all know well often reached out for the brush and easel when musical inspiration was in short supply – Mendelssohn, Gershwin, Edward MacDowell, Granados, Busoni – the list goes on. A stranger to this inventory is the aforementioned Mikalojus Ciurlionis. Ciurlionis died in Poland in 1911 at the tender age of 35, just weeks before Gustav Mahler, but during his short life he produced almost 400 musical compositions and an equal number of paintings and etchings. This true Renaissance Man also published prose and poetry, and made a deep study of history, philosophy, geology and astronomy – and toward the end of his life he became a skilled photographer. The man, obviously, never stopped working, seeking, and sometimes finding, and it is evident that, like the Russian Alexander Scriabin at around the same period, synesthesia (a condition wherein one experiences sensation in one sense, in response to stimulus in another) played a part on both sides of the equation Over 100 years after his death his pictures are slowly receiving the recognition they deserve – his music may as well not exist. Which is baffling when you listen to the quiet beauty of the central andante movement from his String Quartet in C minor (1902).

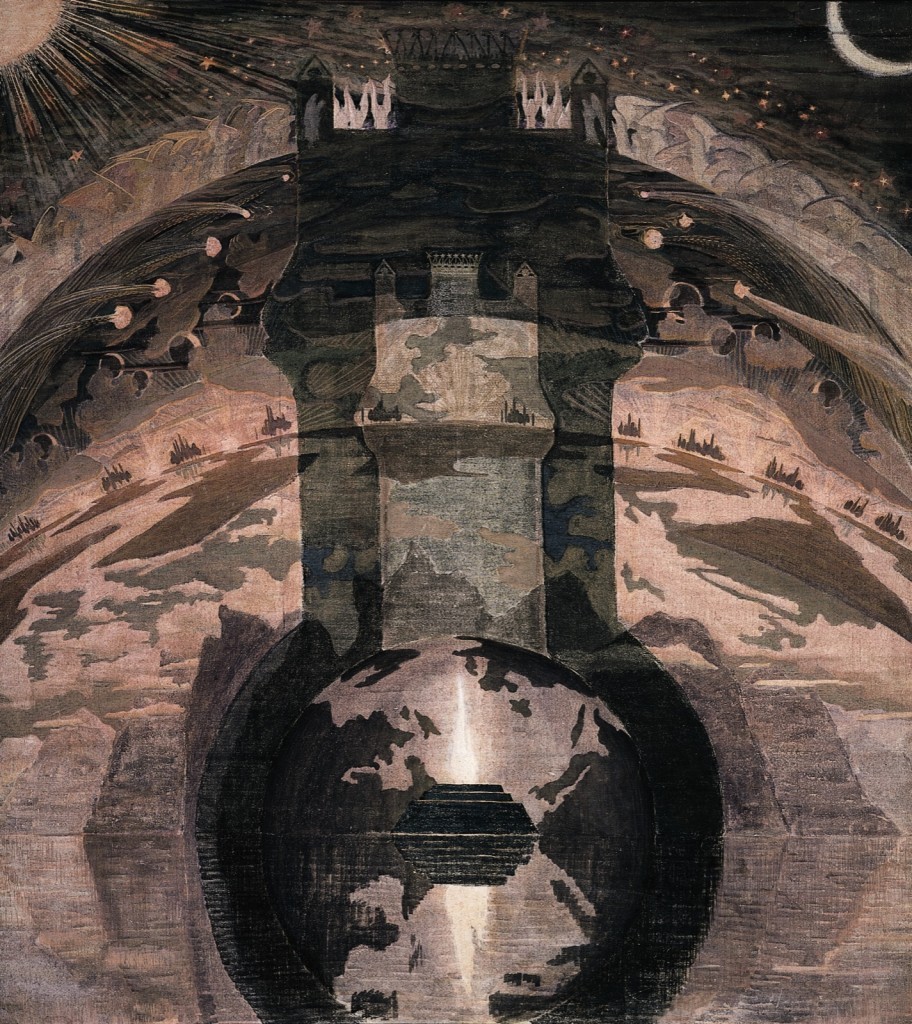

At the top of this post is his final work Rex from 1909, and below is the spooky but rather wonderful Fairy Tale Castle, completed just two years before his death.