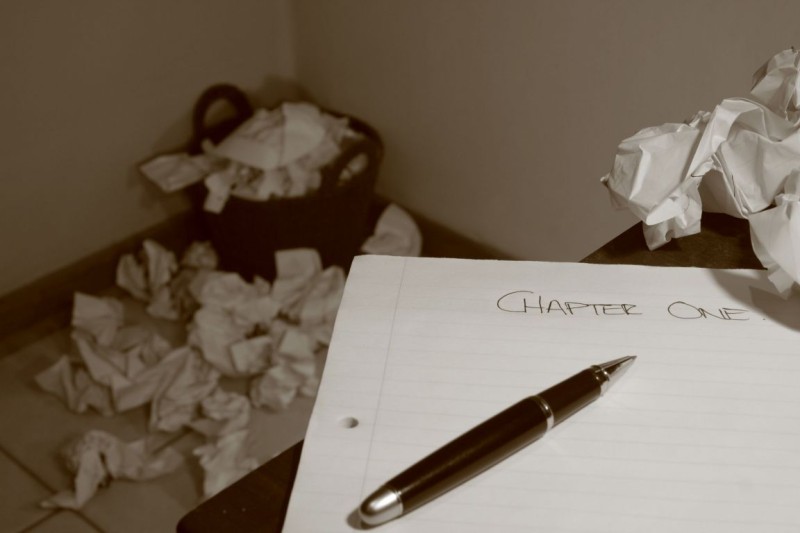

Anyone who has suffered writer’s block might take consolation from the life of John Ferrar Holms. Jonathan Law introduces perhaps the least productive ‘writer’ in the English language…

A while ago on The Dabbler , Mark Pack wrote feelingly about the miseries of writers’ block – of self-doubt, procrastination, and hours spent sweating it under the evil eye of the cursor:

Oh how I learned to hate the blank screen, its emptiness mocking my inability to turn years of accumulated knowledge into even mere scraps of disjointed sentences. No thought seemed the right commencement. No premise the correct starting point. No anecdote a relevant prologue.

Just the blinking cursor …

Now, if there’s one subject on which writers tend to be eerily lost for words, it’s this one – the block. Two attitudes seem to prevail, neither of which makes for verbosity. On the one hand, there’s a superstitious dread of the whole topic – something like the old fear of naming a demon aloud, in case the mere saying becomes a summons and all at once the nasty thing is squatting on your shoulder. On the other, there’s a brusque scorn for any scribbler so weak-minded as to credit such stuff. Call yourself a professional? Then stop your blather and think on Trollope with his stopwatch and his 250 words every 15 minutes. After all, those in other walks seem to get through the day without this sort of fuss. Chiropodists’ block? Ambulance drivers’ block?

I suppose it all goes back to the Romantics, with their interest in the psychology of creation and the view of inspiration as something wayward and fleeting (Shelley: “A man cannot say, ‘I will compose poetry’ ”). The idea that creativity springs from mysterious, hidden sources has as its flipside the idea that such sources may inexplicably dry up. So we find Wordsworth on the cusp of middle age, mourning a power that already seems to be deserting him:

The hiding-places of my power

Seem open; I approach, and then they close;

I see by glimpses now; when age comes on,

May scarcely see at all …

And then there’s Coleridge, of course – a man who found a strange sort of vocation in his failure to live up to the promise of his early genius. The predicament of the blocked artist has rarely been summarized with such fearful concision as in this entry from Coleridge’s Notebook, dated October 30, 1800:

He knew not what to do – something, he felt, must be done – he rose, drew his writing-desk before him – sate down, took the pen – found that he knew not what to do.

***

If I ever get that blocked feeling, I tend to consider the strange case of John Ferrar Holms – both as a consolation (things have never got that bad) and as the most awful of warnings. Probably you’ve never heard of Holms (1897-1934) and probably that’s only as it should be: he has given the world little cause to think of him. If he has any claim to fame, it is the sad and singular one of being quite probably the least productive writer in the English language – an odd status that raises the question of just how little a man can write and still be a ‘writer’. Although widely considered a genius in his time, Holms comes down to us as a mere footnote in the biographies of his friends and lovers, with even the vast lumber room of the Internet retaining barely a trace of his 36 years on earth.

It wasn’t supposed to be that way. As the 1920s wore into the 1930s, those who knew Holms best rarely faltered in their belief that this strange, obsessive man – a manic perfectionist who seemed to regard even the most universally praised writers as sloppy underachievers – was hatching works to make future ages gawp. To his boosters, he was no mere literary hopeful but a being whose gifts of intellect and expression put him up there with the greats: a man to be mentioned in the same breath as Shakespeare or Plato. The poet Edwin Muir, who was never one for hyperbole, stated quite simply: “Holms was the most remarkable man I ever met” – and it’s worth pointing out that Muir had met most of the big English writers of the day. To Muir, Holms possessed a mind of such preternatural strength that it seemed to belong to an unfallen order of creation:

His mind had power, clarity, and order, and, turned on any subject, was like a spell which made things assume their true shapes and appear in their original relation to one another, as on the first day.

Peggy Guggenheim, the heiress and art collector, was another who considered Holms by far the most extraordinary man she had known – again, quite something when you consider that her lovers (to say nothing of her wider circle) included Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, and Samuel Beckett. According to Peggy, who survived a stormy six-year relationship with Holms, being in his company “was equivalent to living in a sort of fifth dimension”. Others to fall under the spell included William Gerhardie, Alec Waugh, and the radio pioneer Lance Sieveking – who believed that if Holms could have overcome his demons he might have been “a literary figure as familiar as any man who ever wrote.”

Well, perhaps, maybe, possibly, who knows? There’s no way of telling. For as it turned out, Holms’s complete works would consist of one short story, a few critical essays, and a handful of unfinished poems.

***

History is, of course, not short of figures who managed to enthral their contemporaries in ways that later generations struggle to understand. More often than not, the explanation has something to do with brilliant talk (Coleridge again) or a charm or charisma that just doesn’t make it to the written page. In Holms’s case, this seems to be at most partially true. Although Alec Waugh described him as “a brilliant talker”, others disagreed, noting that he hardly ever finished a sentence before becoming lost in the maze of his own thoughts. Similarly, Holms’s personality seems to have been lacking in the finer points of attraction, being at once fiercely brooding and oddly passive. In Edwin Muir’s view, “Holms had hardly any personality at all; when he impressed you it was by pure, uncontaminated power”.

It is in the accounts of Holms’s appearance that we get a real clue to the spell that he cast on others. At well over six foot, with a broad chest and shoulders and a mane of flaming hair, Holms had the sort of looks that ought to belong to literary lions but too rarely do. With his sad eyes, sensual mouth, and the small pointed beard he liked to twirl when thinking, people were put in mind of a Spanish grandee, an Elizabethan courtier, or a character out of Dostoevsky: for her part, Peggy Guggenheim claimed that he “looked very much like Jesus Christ.” Alec Waugh noted simply “He was how I expected a genius to look”, while Edwin Muir describes strangers trooping to his lodgings in Prague, just to set eyes on the melancholy red-haired giant.

Indeed, Holms seems to have had a peculiar physical quality that went well beyond his magnificent physique. This is an aspect of his friend that Edwin Muir puzzles over at length in his Autobiography:

In his movements he was like a powerful cat; he loved to climb trees or anything else that could be climbed and he had all sorts of odd accomplishments; he could scuttle along on all fours at great speed without bending his knees; walking, on the other hand, bored him. He had the immobility of a cat too, and could sit for long stretches without stirring.

Peggy Guggenheim also recalled Holms’s “elastic quality,” adding rather ominously, “Physically, he seemed barely to be knit together. You felt as if he might fall apart anywhere.”

As indeed he did: quietly but totally and irretrievably.

***

Not much is known of the early life of Holms. However, one episode is recorded by his great friend and admirer, the diarist Emily Coleman. When Holms was at prep school in England, he was obliged to write the standard weekly letter home. As his fellow pupils filled a sheet or two with the usual chatter, Holms found himself neurotically unable to write a word: when time was up, he hid his disgrace by slipping the blank sheet into an envelope and putting it in the post. Next week, his nervousness was worse, as he knew he would not get away with the ruse a second time: predictably, his parents received another blank letter. The school was informed and hell was duly paid.

Otherwise, Holms’s early years provide few clues, his background being solidly conventional for his class and era. The son of the governor-general of the United Provinces of India, he was schooled at Rugby, where he excelled as an athlete. Rather than university he chose Sandhurst and, with the advent of World War I, joined an Infantry regiment at the age of just 17. At the Front, Holms made a name for himself with a single rather shocking incident. Having stumbled on four Germans breakfasting under a tree, he took them on single-handed and somehow managed to beat their brains out (with what is not clear). For this Holms was awarded the MC, although it is said that he never spoke of the matter, regarding it as vaguely comic and disreputable.

Having survived the Somme, Holms was captured in the great retreat of March 1918 and spent the rest of the war in prison camps at Karlsruhe and Mainz. At the latter, fellow prisoners included the writers Alec Waugh (Evelyn’s brother) and Hugh Kingsmill – not to mention John Milton Hayes, author and declaimer of The Green Eye of the Little Yellow God. As the men had no duties and books were plentiful, they spent most of their time talking, reading, and writing; Waugh would later refer to his education at the ‘University of Mainz’. It was here that Holms first conceived the ambition of being a writer; less happily, it was here too that he seems to have developed a deep depressive streak – for some years after he is said to have carried a service revolver at all times, just in case the urge became too strong to resist.

At first this writing thing went rather well. Although he planned more works than he ever produced, Holms made the right sort of contacts and in the 1920s his byline began to appear in The Calendar of Modern Letters, a highbrow quarterly often seen as the forerunner of Scrutiny. These pieces include his one completed work of fiction – an apparently excellent short story entitled ‘A Death’ – and a number of reviews notable for their length and severity (Wyndham Lewis gets a roasting and Mrs Dalloway is dismissed as “aesthetically worthless”).

Otherwise these were years of restless travelling: Holms had run off to Europe with a married woman named Dorothy and the couple knocked about in France, Germany, Austria, and Yugoslavia. It all seems a bit aimless but Holms could no doubt have claimed to be gathering material. In 1928 this peripatetic existence brought them to the home of Emma Goldman, the famous anarchist, in the South of France – and it was here that Holms had his first fateful meeting with Peggy Guggenheim (below), the woman with whom he would spend the rest of his life. After a certain amount of melodrama, Guggenheim left her husband and Holms abandoned Dorothy (whose main emotion seems to have been relief: she told a friend that living with Holms was like being a “governess to a baby”).

This change of partners did nothing to encourage Holms in a more settled way of life, although with Peggy’s millions – she had inherited a fortune when her father went down with the Titanic – things must at least have been more comfortable. Peggy would later write with pardonable exaggeration: “John Holms and I did nothing but travel for two years. We must have gone to at least twenty countries and covered ten million miles of ground.” Finally, in 1931, they settled after a fashion in London. They also took Hayford Hall, a remote Tudor manor on the edge of Dartmoor, as their summer home. Here the wine flowed as freely as the talk and house guests included Antonia White, Emily Coleman, and Djuna Barnes, who began her once-celebrated Nightwood at the hall (the book is dedicated to Holms and Peggy). It was also here – in the gloomy, crenellated, ivy-smothered house that is thought to be the model for Baskerville Hall – that Holms’s admirers came to realize what he had probably long recognized himself: that he had not written a damned thing for years, and was now hardly likely to.

***

In his marvellous Autobiography, Edwin Muir spends page after page trying to get to the bottom of his great friend Holms and the strange paralysis that captured him. By a familiar paradox, Holms’s high ambition, exacting standards, and sense of his own gifts are seen as a major source of his block, and hence of the guilt and despair that only dragged him down further:

Though his sole ambition was to be a writer, the mere act of writing was an enormous obstacle to him: it was as if the technique of action were beyond his grasp, a simple, banal, but incomprehensible mystery … He knew his weakness, and it filled him with the fear that, in spite of the gifts which he knew he had, he would never be able to express them; the knowledge and the fear finally reached a stationary condition and reduced him to impotence. He was persecuted by dreadful dreams and nightmares.

Guggenheim’s analysis is very similar, although she is frank enough to mention one other calamitous factor – the booze that played an increasingly central role in the Holms psychodrama:

Since no one else shared his extraordinary mental capacity, he was exceedingly bored when talking to most people. As a result, he was very lonely. He knew what gifts he had and felt wicked for not using them. Not being able to write, he was unhappy, which caused him to drink more and more. All the time that I was with him I was shocked by his paralysis of will power. It seemed to grow steadily, and in the end he could hardly force himself to do the simplest things.

These accounts are perhaps clear enough but carry a hint of something still more perverse: the way in which, for certain writers, failing or refusing to write can become an assertion of superiority. If Holms didn’t think most people were worth talking to, why should he debauch his “extraordinary mental capacity” in attempting to write for them? Perhaps above all else, Holms feared seeming pedestrian (Muir: “he could scuttle along on all fours at great speed without bending his knees; walking, on the other hand, bored him”). In a barmy sort of way, not writing can seem like a means of holding on to the purity and grandeur of one’s original ideals as an author. There’s a feeling that most writers get at times, that the stuff you manage to get down on paper falls terribly short of the shining work glimpsed in your imagination – so far short as to be almost a kind of betrayal. If you are not careful, a too-exalted sense of the things you would like to write, or ought to write, can cast a killing shadow on the things you are at all likely to write.

The malaise that afflicted Coleridge – the most celebrated of blocked writers –was at least partly of this kind. “Better to do nothing,” he writes at one point in the privacy of his Notebook, “than do nothings.” It’s a moment of the most tragic self-deception but we can be fairly sure that Holms would have concurred. At times Coleridge seems to have felt that there was something slightly vulgar about making or doing anything at all – even in the Highest conceivable quarters. “Something inherently mean in action,” he suggests in the Notebook. “Even the creation of the universe disturbs my idea of the Almighty’s greatness – would do so but that I perceive that thought with Him creates.” Both Coleridge and Holms, you feel, would have loved to be able to create by thought alone – and for reasons that involve a kind of cosmic snobbery as much as simple idleness.

Certainly, Holms’s lack of achievement did nothing to mitigate a lordliness of manner that others found increasingly hard to take: Willa Muir (Edwin’s wife) declared that she would rather die than spend another evening listening to him spout while Djuna Barnes compared his social style to “God come down for the weekend”. As drink and depression took hold, there were horrible scenes of ranting and even violence. In her autobiography Peggy recalled an occasion on which “he made me stand for ages naked in front of the open window (in December) and threw whiskey into my eyes”. She also told Emily Coleman: “He gives me a sense of death”.

When the end came, it was as strange and surprising as anything in Holms’s life. In the summer of 1933 John Holms went riding on Dartmoor and suffered a slight fall when rain misted his glasses. His injuries were trivial – a couple of cracked bones in the wrist – but they continued to bother him and he agreed to an operation. During the routine procedure, carried out at Peggy’s London home in January, he simply and unaccountably slipped away. It seems that years of heavy drinking had left his body unable to cope with the anaesthetic. In his diary Muir wrote: “I cried at the thought that he had died so easily, for that was the saddest thing of all: as if Death had told him to come, and like a good child he had obeyed”. Muir was appalled, too, by the ghastly cremation “in that brick chapel, with its clergyman who looked like a clergyman”, finding it “too horrible for tears”. Only six mourners were present.

Despite his futile life and oddly bathetic death, Holms remained an urgent presence to those who had known him. Peggy Guggenheim never got over her strange lover and is said to have jinxed many subsequent relationships by her constant harping on his ‘genius’. Emily Coleman went still further in making a cult of Holms, writing him long poems and convincing herself that she was channelling his spirit from the afterlife. And then there is Edwin Muir, whose poem ‘To J. F. H.’ records what he took to be a supernatural experience in the summer of 1941. While walking down a city street Muir was passed at high speed by an army motorcyclist, who suddenly turned his head: impossibly but unmistakably, the face was the beautiful face of John Ferrar Holms.

The clock-hand moved, the street slipped into its place;

Two cars went by. A chance face flying past

Had started it all and made a hole in space,

The hole you looked through always. I knew at last

The sight you saw there, the terror and mystery

Of unrepeatable life …

Pardonable exaggeration: 10 million miles of ground in two years is 400 times around the world in 24 months, a bit more than 16 times around the world every month, ergo around the world and then some every two days. But it is reasonable that Peggy Guggenheim would have had a very different notion of millions from what most of us have.

And I wonder whether her notion of extraordinary mental capacity was wholly separable from the robust frame and flaming red hair. That he was brilliant I can suppose. To believe that in an age when Einstein, Bohr, Wittgenstein, Hilbert, Godel, Joyce, Eliot, etc. etc. were alive and productive nobody shared his mental capacity, I would need other witnesses.

But the writers who gain reputation with every book not published are an interesting bunch. In America, J.D. Salinger and Harold Brodkey come to mind. Still, they published more than Holmes did.

Fascinating – thank you very much. In true Holms style, I having nothing more to say.

“I having”? Oh dear.