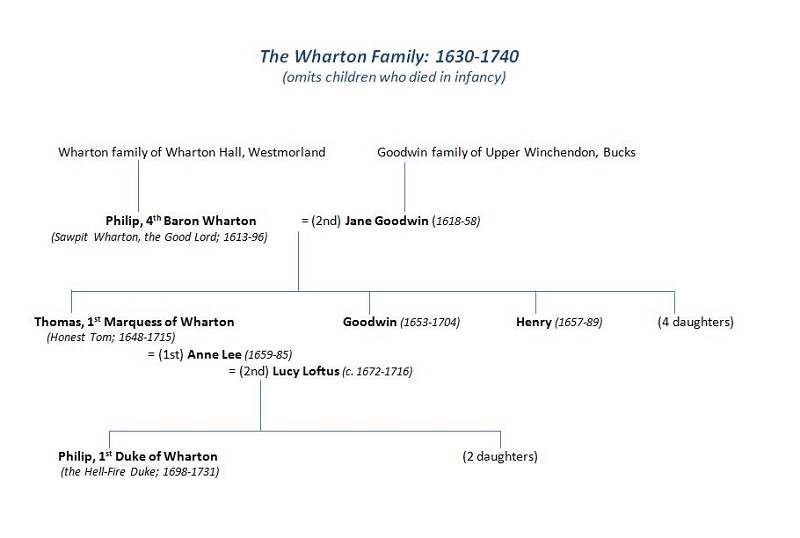

The Whartons of Winchendon is a new serialisation of Jonathan Law’s latest book, which is published for Kindle by Dabbler Editions and available to buy from Amazon now.

In this third episode we meet Philip’s son Tom Wharton, who rose to political power but also became embroiled in religious and domestic scandal. Did he really relieve himself in a church pulpit?…

As he entered his autumn years, Philip, 4th Baron Wharton could look back with some pride on a life spent in the service of three great but often embattled causes – the Reformed Protestant religion, the liberty of Parliament, and the dynastic ambitions of the Wharton family. His chief concern now was the grooming of young Tom, his son and heir, to carry the great work forward.

On the face of it, this might have seemed a desperate project. By the time he came of age, Tom Wharton had turned violently against the Puritan ethos of his father’s house – a world of “Geneva bands, heads of lank hair, upturned eyes, nasal psalmody, and sermons three hours long” (in the colourful words of Thomas Macaulay). Although he was already becoming known as a rider and owner of racehorses – Careless, Snail, and Wharton’s Gelding would all become legendary in the annals of the turf – Tom’s chief notoriety was as a rake and libertine. He was also making a name as a swordsman and duellist: a man who boasted that he had never issued a challenge, never refused a challenge, and – once engaged – had never lost a fight. Yet however wild his antics, Tom managed his rebellion so skilfully that he never provoked an open breach with his father, to whom he remained outwardly submissive. The son had clearly learned something from old Sawpit’s dealings with princes and Protectors. To his headstrong and occasionally reckless qualities, Tom Wharton added a strong dash of his father’s circumspection.

In the light of later events, Tom’s way of keeping a cool head in the midst of his indiscretions has a smack of Shakespeare’s Prince Hal – the difference being that Tom Wharton would eventually turn himself into a Great Man without any nonsense about reforming his morals. As in the Hal plays, too, there’s something a bit Oedipal about Tom’s relations with his devoted but oh-so demanding father. The Restoration bloods had a favourite bit of doggerel:

May it please God to shorten the life of Lord Wharton

And set up his son in his place,

Who’ll drink and who’ll whore

And a hundred things more

With a grave and fanatical face.

It was even whispered that Tom Wharton had written these words himself (as the world would soon learn, he had a way with a doggerel rhyme).

***

If Lord Wharton was insistent on one thing, it was that Tom should marry and marry well. After a long search a suitable bride was found, with Tom himself playing little or no part in the process. As well as being rich and well-connected, Anne Lee was clever, bookish, and serious minded; the couple married in 1673, when he was 25 and she just 14. Although Tom seems to have had no strong feelings about the girl – whose character and interests were so far from his own – the match was welcome for quite other reasons. Not only did he come into good money, but the old place at Winchendon now became his by way of settlement. Although he had few sentimental feelings, Tom seems to have loved his childhood home and the North Bucks countryside where he had first learned to ride. The house had another important advantage; with its relative remoteness, Winchendon allowed Tom to escape his father’s care, just as it had given the old lord his freedom from Cromwell. He could now pursue his various pleasures without risk of censure. At Quainton, a few miles to the north, he would build his own private racecourse – and (it is said) a house for his latest mistress. He also had an important new interest, and one that his father could wholeheartedly endorse; in 1673 Tom was elected MP for Wendover, the first of a long series of Buckinghamshire constituencies. With one thing and another, Anne could not expect a great deal of his attention.

If Tom could not work up much interest in his young wife, modern scholars have found Anne Wharton rather fascinating. An orphan almost from birth, she had been brought up mainly by a Puritan grandmother but also by her uncle, the notorious poet and libertine John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester. Anne herself showed early signs of literary talent and continued to write throughout her marriage, producing lyrics, satirical pieces, and a full-length verse drama, Love’s Martyr. Although her work achieved little circulation in her own day, it was praised by the cognoscenti and has recently attracted the attention of feminist critics; Germaine Greer published some thirty of Anne’s poems in 1997 and a dozen more have since come to light. The one poem printed in Anne’s lifetime was almost certainly her best – a heartfelt elegy on the death of her uncle Rochester, whom she clearly adored.

As his parliamentary career took off, and Anne signally failed to produce the expected heir, Tom seems to have neglected her more and more openly. In the circumstances, it is hardly strange that Anne should have looked elsewhere – but curious that she turned to Tom’s younger brother Goodwin, a penniless eccentric. After an attempt to set up as an inventor, Goodwin had tried to solve his chronic money problems through a series of increasingly improbable ventures, including diving for sunken treasure in the Hebrides; with the ignominious failure of all these schemes, he was now pinning his hopes on alchemy and the acquisition of magic powers.

To his stoutly pragmatic family, Goodwin was at best a puzzle and at worst an incorrigible ninny. Possibly, it was a shared sense of exclusion from the Wharton world of wealth and power that drew the two together. Whatever the case, Anne clearly liked the young man and the two held several assignations in 1680-81. For the gory details we have to rely on Goodwin’s later memoir – an utterly bizarre but in its own way very candid document. Although only too aware that they would be committing incest as well as adultery, Anne had reached a point where she was prepared to risk her immortal soul, stating roundly that “she could be content to be damned rather than not have her desires”. As it turned out, her fears were unnecessary. On his first nervous attempt to seduce her, Goodwin experienced an “ejection” of seed that made him “incapable” of further action. A second attempt would be baulked by the arrival of Anne’s period. Thereafter the heat seems to have gone out of the relationship, although Goodwin would continue to see her in dreams and visions for the rest of his life. If his memoir can be trusted, he would go on to enjoy similarly frustrated affairs with his own stepmother (Lord Wharton had remarried), not to mention three queens of England and two queens of Fairyland. But these are matters to which we shall return.

In point of fact, Goodwin may have had a very lucky escape. Anne had been experiencing health problems for some time and most scholars think that her symptoms – which included eye troubles and violent convulsions – indicate syphilis. If this is correct, then the obvious culprit must be Tom, who had presumably infected her with the disease and neglected to mention the matter, thus denying her such treatment as was available. There is, however, another possibility: according to Goodwin, in the years before her marriage (at 14!) Anne had been “lain with long by her uncle, my Lord Rochester”. It is generally assumed that Rochester’s death, in 1680, had been caused by chronic alcoholism and a nice cocktail of STDs. By the summer of 1685 it must have been clear that Anne, too, was dying – and dying very hard; the poet Robert Gould would write movingly of her last agonizing weeks:

When ev’ry Artery, Fibre, Nerve and Vein

Were by Convulsions torn, and fill’d with Pain …

Although Goodwin used his occult powers to send several angels to her bed, he did not visit in person; Tom, it seems, did, and achieved some kind of reconciliation with Anne before her death that autumn, still aged only 26. When Tom brought the body back to Winchendon, he insisted that his wife was buried in fine silk, rather than the wool then required by law – a tiny act of amends that cost him a fine of 50 shillings. On the opening of Anne’s will, it was found that she had left her entire fortune to Thomas Wharton.

***

These years – the early 1680s – were also the years of Tom Wharton’s gradual rise to prominence in national affairs. During the Exclusion Crisis of 1679-83, Tom would be among those MPs who pressed most vigorously to exclude Charles II’s Catholic brother, James, from the throne – a group soon nicknamed the Whiggamores or Whigs. It was a time of violent faction and of plot and counterplot in which the country sometimes seemed to stand on the brink of a second civil war. In general, Tom navigated these dangerous waters with a tact and sense of timing of which his father can only have been proud; in his opposition to King and court, he seemed to know just how far he could push at any particular time without endangering the cause (or his own head). There is, however, one extraordinary exception to all this – an incident so grotesque that it would give his enemies ammunition for the rest of his life.

By 1682 there was a growing feeling that the Whigs had overplayed their hand, alienating by their violence many good Protestants who also had a devout belief in social order. In particular, the Church leadership had united behind James on the premise that a Catholic king would be less threatening than a Roundhead revival. It seems to have been a deep frustration with this state of affairs that prompted Tom to the most outrageous faux pas of his career. One evening that summer, Tom and his even wilder brother Henry – an infamous brawler – got drunk with a group of like-minded friends and broke into the church at Great Barrington in Gloucestershire. The intruders rang a ragged peal on the bells, cut the bell-rope, and committed further acts of vandalism, including ripping the church Bible. Worse still, before departing into the night, Tom had allegedly “pissed against a communion table” and “done his other occasions in the pulpit”.

The Great Barrington incident is the one occasion on which the recklessness of Tom’s private life seems to erupt into the calm calculation of his political career. An interesting question is what, if anything, this “grievous prank” says about his religious beliefs. Does the incident reveal the unreconstructed Cromwellian lurking under the Restoration rake? Or is it true that, as his enemies always said, Tom Wharton was really an atheist in dissenter’s clothing? From a political point of view, the evening’s work was clearly an embarrassment – and yet it did him less harm in the long run than might have been expected; it would not bar his path to some of the highest offices in the land. In our own irreligious but increasingly censorious age, we can only boggle at how a full-on pulpit-pooping incident, involving say Michael Gove or Yvette Cooper, would play with the focus groups or those all-important swing voters in key marginals. A Twitter storm there certainly would be.

As it happened, the scandal of Great Barrington was soon overshadowed by more deadly concerns. In 1683 the discovery of the Rye House Plot – a conspiracy to murder both Charles and James as a prelude to general insurrection – provided the government with all the excuse it needed to crack down on the Whig leaders, a procession of whom went to the scaffold or fled abroad. Historians still disagree about how far the plot was a serious threat and how far it was talked up by the authorities. Although Tom Wharton was not named among the suspects, a report that some of the plotters were hiding at Winchendon led to the house being searched from top to bottom; a modest cache of arms was removed – enough guns, swords, and body armour to equip perhaps ten cavalrymen. With all his wonted chutzpah, Tom argued for their return, pleading that these things were essential for his own safety: were there not poachers and footpads in Bucks, like anywhere else, and especially so in these unsettled times? We don’t know if he got his weapons back; but the matter went no further.

Despite the best efforts of the Whigs, James duly acceded to the throne in 1685 – an event followed swiftly by the debacle of Monmouth’s rebellion, a botched attempt to replace the new king with Charles’s illegitimate but Protestant son, the Duke of Monmouth. Once again, the precise role of the Whartons is uncertain. Although there is every reason to think that they were approached by Monmouth’s agents, it seems they were far too canny to commit themselves beyond the point of return. Tom had spent a good deal of time with the Duke in his horse-racing days, and with his usual acute judgement of character seems to have decided that this was not a man to whom he wished to entrust his life. Nevertheless, in the aftermath of Monmouth’s defeat there are stories of two carriage-loads of arms being removed secretly from Winchendon and put aside for future use (the time would not be long). It was at this moment, too, with wild accusations flying up and down the land, that old ‘Sawpit’ Wharton decided that it might be prudent to travel to the Continent for his health. According to Buckinghamshire legend, he would bury some £20,000 worth of treasure (in today’s terms, over £2 million) in the Chiltern beech woods before taking his leave, half expecting never to return. After a year in France and Germany, he would find his way back just in time for the General Amnesty. The treasure, it is said, was never found.

There is also a family tradition that while abroad old Philip found occasion to confer with William, Prince of Orange, the Protestant leader with the closest links to the English throne. Although historians have found no evidence for this, it would not be long before others would be looking in the same direction. In the summer of 1688 seven peers of the realm would write secretly to William inviting him to invade England; according to some accounts, the letter was drafted by Tom Wharton. Whether or not this is so, Tom clearly felt that the time for caution was past. He and his soldier brother, Henry, were now leading lights in the ‘Treason Club’, a group that met at the Rose Tavern in Drury Lane to arrange the army defections that would soon make James’s position impossible. Tom’s greatest contribution to the ‘Glorious Revolution’ may, however, lie elsewhere; he is generally credited with writing the words to Lillibullero, a song satirizing James’s Irish policy that would sweep through the army and then the country. Tom would later boast of having rhymed a king out of three kingdoms and sober historians would go a long way towards agreeing (Bishop Burnet would comment that “never did so small thing have so great an effect”). When William finally landed at Torbay, Tom immediately rode west with some 60 picked men and a large haul of weapons. Within days, King James would have fled the country never to return.

With the triumph of the Revolution, the great and palmy days of the Wharton family were about to begin. As the first important figure openly to declare for William, Tom’s future was assured; a grateful monarch would very soon make him a Privy Councillor, the first in a long string of offices and titles. As for old Wharton, his forty-year waiting game was at an end and he could live out the rest of his days in a spirit of nunc dimittis. He had seen the triumph of the three great causes to which he had given his life; the rights of Parliament were vindicated, a Protestant king was on the throne, and with the elevation of young Tom, who could say where the glories of the Wharton family might end? He could hardly know that in little over 30 years the family’s wealth, power, and titles would all have vanished like dew from the sheep pastures of Winchendon.

fabulous stuff, although I feel sorry for whoever had to clean up the church