In the penultimate part of our serialisation of The Whartons of Winchendon, Jonathan Law addresses the question: ‘Just how mad was Goodwin Wharton?’ …

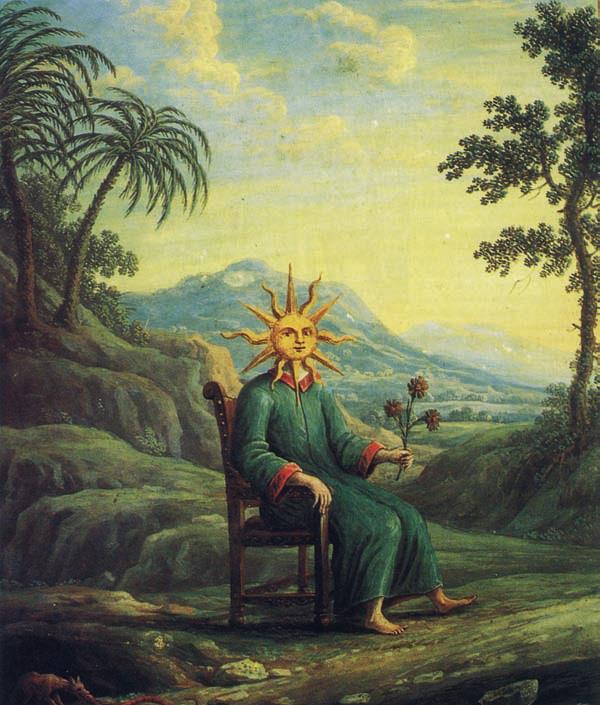

Although the Glorious Revolution made the Wharton family one of the great powers in the land, the new regime was at first slow to recognize the merits of Goodwin – Lord Wharton’s second son but also (as we know) the Emperor of the Fairies and the unacknowledged Solar King of the World. This was not for any want of effort on his part. Throughout 1689 he was a frequent visitor to Whitehall and Hampton Court, where he waited expectantly on King William and Queen Mary. After a while he began to perceive that this Queen Mary, no less than her namesake and predecessor, was hopelessly in love with him, although she was forced to stifle her emotions for form’s sake. During these months Goodwin became, at least in his own eyes, something of a confidante of the Queen, and began to entrust her with some part of his secret knowledge – signs, prophecies, wonders.

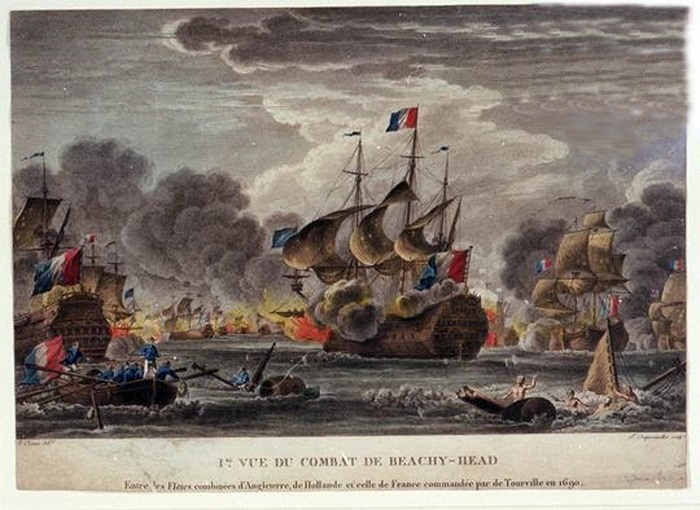

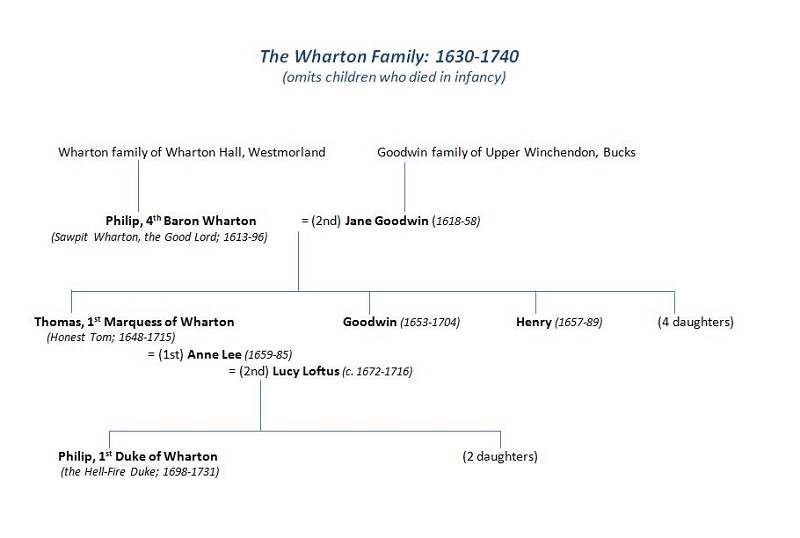

The voices and visions that had dominated Goodwin’s life for six years had in fact gone rather quiet (his last direct order from God had been a command to sleep with his sisters and half-sister; he had made no real effort to comply). Rather surprisingly, when Goodwin did begin to climb the greasy pole of late Stuart politics it was in a workaday style that owed nothing to his more specialized interests. In 1690 he was returned to Parliament, a seat having become vacant through the death of his brother Henry. Anyone expecting a repeat of his first, disastrous stint as an MP would be disappointed. Goodwin spoke frequently, knowledgably, and soberly on a range of subjects and showed a particular expertise in military and naval matters. He was soon sitting on three committees and began to earn a reputation for diligence and attention to detail (a legacy, perhaps, of his occult studies, which had in their own way been very painstaking). His esoteric interests had not been abandoned, however, and at times would overlap strangely with his new duties. During the Battle of Beachy Head in 1690, for example, Goodwin threw himself into designing a mortar to lob fireballs at the French fleet; only readers of his autobiography would know that he also ordered his fairy subjects to steal invisibly on board and water the French gunpowder. Some months earlier he had likewise set down plans to occupy his fairy kingdom by force, using wild fire and other conventional munitions.

Goodwin’s changed fortunes are perhaps best illustrated by the circumstances in which, after some 15 years, he renewed his search for sunken treasure off the coast of Mull. In the 1670s Goodwin had been very much the lone maverick; now, in July 1691, he arrived in Tobermory with two naval vessels, a troop of 100 highlanders, and the backing of several rich investors. Again, only a reader of Goodwin’s memoir would know that his late arrival was caused by a long wait for a fairy named Jeffrey – reputedly an expert diver – and for the magical breathing apparatus that had been promised him by the angels. No treasure was recovered: but Goodwin did manage to salvage 14 cannon from a sunken vessel, which enabled him to return to London in triumph, something of a celebrity.

The mid-1690s would see the culmination of Goodwin’s career as a public man. In Parliament, he was increasingly recognized as an expert on finance and coinage (perhaps appropriately, given his lifelong obsession with treasure). He drew up and presented bills, helped to manage the legislative programme of the Whigs, and served on two naval committees and four or five others. In 1694 he was gazetted a lieutenant-colonel of cavalry and had his portrait painted in body armour and full wig, every inch the Williamite soldier-statesman. An opportunity for front-line service arose that June, when Goodwin helped to plan and lead the naval assault on Camaret Bay in northern France – an ill-fated engagement in which he nevertheless showed a certain mad courage. Like Philip some 30 years later, it seems that Goodwin felt a need to dispel the taint of cowardice that had clung to the Wharton name since Edgehill. When Old Lord Wharton died in 1696, Goodwin became financially independent for the first time in his life and was able to live in a style befitting his new status. Finally, in April 1697, he was appointed one of the Lords of the Admiralty at a salary of £1,000 p.a.; as Wharton’s biographer points out, this made him one of a small group of men responsible for “managing … the most complex industrial organization in England”. Goodwin leased a country estate in south Bucks, served as a JP, and was elected knight of the shire: to all appearances, a solid, standard-issue establishment figure.

This very conventional success story was cut short in March 1698, when Goodwin experienced a disabling stroke. By the time he recovered, the Whigs had lost the ascendancy and in 1702 King William was replaced on the throne by Anne, a strong Tory. Amongst the Whigs, it was probably only Goodwin who could see an upside to these events. He had long been aware of Anne’s secret love for him and now learned (in a vision) that she was planning to marry him on the imminent death of her husband. In this way the prophecies would find their long-delayed fulfilment and he would at last become master of England.

Before this could come to pass, however, Goodwin would experience the heaviest blow of all – the death, in January 1703, of Mary Parish. As she lay dying, Mary revealed one last wonder; although in her early seventies, she was again with child by Goodwin. Nothing could have been more characteristic of this marvellous woman – although the child, of course, proved somewhat notional. After her death Goodwin would total up Mary’s conceptions over the past 20 years and find that they came to an impressive 107.

The demise of his partner in fantasy left Goodwin utterly lost and bereft. Although Mary had fleeced him royally for two decades and in 1685-86 may even have pushed him into total madness, it is hard to see her effect on his life as only negative. As Goodwin’s biographer, J. Kent Clark, sums up: “she had constructed and described to him a dramatic world in which he had played the central role. She had made his life significant.”

In some ways the disappointments of Goodwin’s last years were as serious as any he had faced. Although his country seat was only a few miles across the fields from Hounslow, his fairy subjects stubbornly failed to send for him, their rightful monarch. Queen Anne continued to conceal her love. And most inexplicably of all, Mary failed to come to him after death, despite her firm promises to do so. But Goodwin never lost hope, never abandoned faith. One of his last acts was to acknowledge his teenage son Hezekiah – whose true parents were God knows who – and to make provision for him in his will. The former Lord Commissioner of the Admiralty, Emperor of the Lowlands, and Solar King of the World died peacefully in October 1704 and was buried in the Wharton family vault at Wooburn.

***

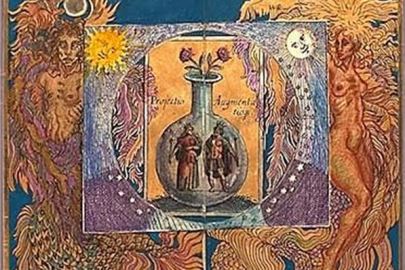

How mad was Goodwin Wharton? On the face of it, it’s hard to dissent from Roy Porter’s article in the DNB, which concludes that Goodwin’s memoir “ranks high in the annals of psychopathology”. Porter’s earlier study in Psychological Medicine (1986) has the unmisgiving title ‘The Diary of a Madman’. But as Porter himself acknowledged, and others have pointed out, none of Goodwin’s beliefs, considered in isolation, was particularly unusual for his age. Alchemy was not yet entirely separated from chemistry and found adherents as worldly as Isaac Newton and Richard Steele; belief in omens and prophecies was almost universal; and few Christians would have disputed the possibility, at least, of communication with angels or spirits. Even a belief in fairies and fairy gold would have been far from uncommon in the more rural parts of England. In her absorbing study of fairy lore Troublesome Things, Diane Purkiss emphasizes how in the 16th and 17th centuries “fairies were part of the growing enterprise culture … Like modern punters buying tickets in the National Lottery as a way of magically transforming their lives, early modern people sought out fairies … not in the interests of morality or soul uplift, but as a means of getting rich”. This is plainly so in Goodwin’s case; his interest in fairy treasure was to this degree perfectly hard-headed and quite free of the woozy romanticism of later fairy-fanciers, such as Rudolf Steiner or Lord Dowding.

It is with all this in mind that Katharine Hodgkin opens her Madness in Seventeenth-Century Autobiography with an account of Goodwin’s memoir – and the plain statement that it is “not an autobiography of madness.” Goodwin’s family and friends may have found him infinitely exasperating, but no one seem to have believed that he was incapable of making rational decisions or looking after his own affairs. Indeed, his later career as a politician and bureaucrat shows a man who was more than usually organized, attentive to detail, and capable of marshalling the facts of a case. If his memoirs had not survived, he would probably be remembered as rather a dull dog; a middle-ranking Whig politico with a gift for administration. One lives in hope, I suppose, that even now Eric Pickles or Ed Balls is writing an account of his adventures with the Queen of the Fairies.

Where Goodwin might fail the sanity test is suggested by that popular piece of Internet wisdom, variously palmed off on Einstein and Franklin among others: “The definition of madness is doing the same thing over and over again but expecting a different result”. Goodwin’s peculiar incapacity for learning from his errors – 107 phantom pregnancies – is one of the things that makes him so extraordinary (and, in a way, so endearing). More disturbingly, of course, there are the hallucinations, the orders from God, the assumption that every woman he meets is hopelessly in love with him. One plausible, if rather prosaic, hypothesis is that Goodwin may have been affected in some way by his diving experiments: not enough oxygen to the brain.

Although Goodwin’s career is in most ways sui generis, it also seems to offer a twisted fit with the age – a looking-glass version of its events and preoccupations. At times, this involves a very innocent sort of lunacy; the conjunction of Lords of the Admiralty with fairies could be straight out of Iolanthe. At others, the effect is a good deal more perverse – like reading English history as rewritten by Neil Gaiman or Alan Moore. Only from Goodwin can we learn how James II fought back against William of Orange by hiring six wicked conjurors to cast spells; or how Charles II knighted a certain John Tomson for walking “perfectly on foot without any device or trick over the Thames straight from Whitehall without being any otherwise wet than his feet a little”. Just to mix things up, it’s a pretty deranged period of English history anyway, this bit between the Restoration and Queen Anne: paranoid, hysterical, full of hoaxes, riddles, mass hallucinations. Such events or non-events as the Popish Plot, the Rye House Plot, the Meal-Tub Plot, and the Warming-Pan Plot seem in some lights as strange as anything dreamt by Goodwin.

And if Goodwin’s adventures hold up a distorting mirror to the times, still more closely do they reflect the values and obsessions of his own family, the briefly all-powerful Whartons. Old Philip’s intense inward-looking religion; Tom’s pursuit of power and sex and his complicated relationship with the truth; the grim family passion for getting money and getting heirs: all have their equivalents in the splendidly warped world of Goodwin and Mary Parish.

With one thing and another, I think it might be time that I visited Winchendon again.

Riveting reading! And I now know what excuse to tell my workmates when Im late for a meeting by saying “I’m waiting for my fairy, Jeffrey”

I’m still unimaginatively using “too many immigrants on the motorway” but I dare say this might be just as convincing.

Didn’t Nige once mount a convincing argument to the effect that you should never trust anyone named Jeffrey (as opposed to Geoffrey)? Or did I dream that?. It seems to apply in the fairy world as well.