Dabbler Editor Brit talks to graphic artist Tim Lane about his unique, disturbing, five foot-long artwork Anima Mundi…

At the height of the rare scorching summer just gone, a lorry full of candles caught fire on a main artery road out of Bristol, clogging the entire city with fuming traffic. (Bristol’s traffic flow always operates right on the cusp of breaking point, so any mishap brings it to a halt.) I abandoned my car on Frogmore Street and made my way on foot between the sadly melting motorists towards the Floating Harbour. There my spirits rose. The water glittered beautifully blue in the six o’clock sunshine and a warm breeze teased the flags of the good old SS Great Britain. Away from the traffic noise there floated soft summer sounds, the clinks and murmurs of drinkers enjoying themselves after a day’s work. Yes it was lovely all right. Just the sort of day to go into a gallery to look at pictures of body horror, death and Hades.

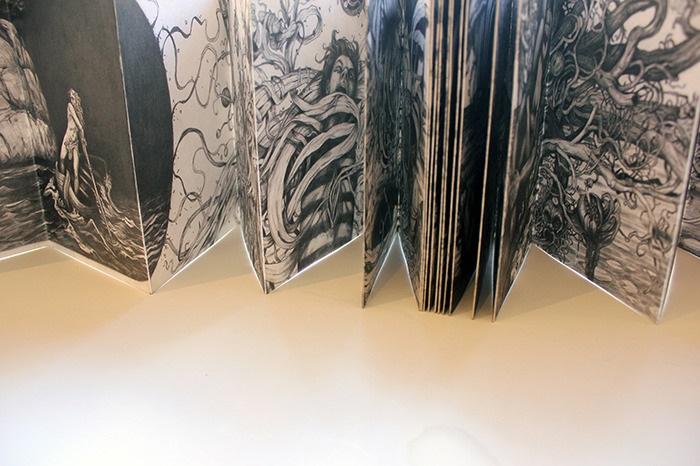

For such are the preoccupations of Tim Lane, a Bristol-based graphic artist of whose work I am a keen admirer and nascent collector. His latest piece was being exhibited at Purifier House, a pop-up location for the ‘nomadic’ Antlers gallery, and it is really something else. Anima Mundi is a five-metre long graphite drawing, concertina-folded into a thick book, the fruit of two years’ labour. The viewer can turn the pages like a novel, or unfurl the work to its full length, or – and this is the really clever bit – fold the pages in dozens of different ways to form new pictures and stories, as the lines from different parts of the whole are designed to marry up when pushed together in new combinations.

A print run of the piece was crowdfunded on Kickstarter, smashing its target. Most of the media publicity focused on the unusual (as far as I know, unique) form, because it required such skill and painstaking cleverness – and those things are always interesting. It’s fun to play with and a terrific conversation piece to have on your bookshelf. But Anima Mundi is also interesting for its content, the product of an exceedingly strange imagination.

Typically, Lane’s work will take some element of a mythological story and warp it, peppering it with Freudian symbols and anachronistic objects to create striking, often disturbing dreamscapes. Artistically, he sits somewhere between a figurative illustrator, a horror graphic novelist and a Surrealist.

Given that, one imagines him as a forbidding, vaguely vampiric character, scribbling through the night in some crumbling garret surrounded by skull-shaped wine goblets and macabre stuffed beasts. In real life Lane is tall and does loom somewhat, but he’s affable and slightly awkward. He talks self-deprecatingly about his art, but fluently, knowledgeably and sometimes even fervently about his interest in mythology and how it informs his stream-of-consciousness approach.

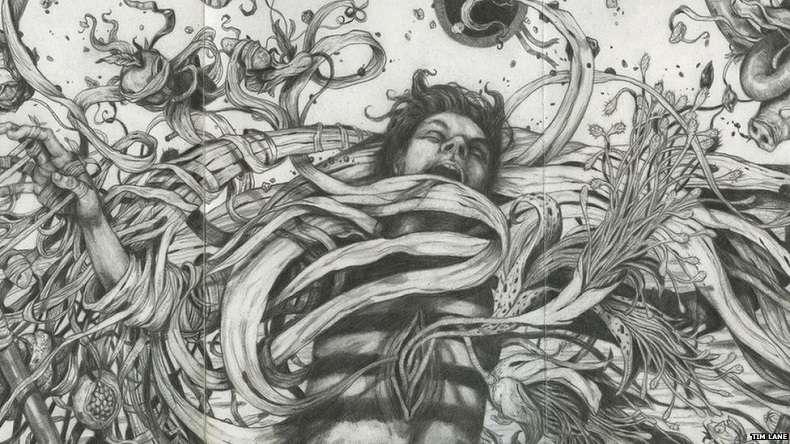

Anima Mundi is his most elaborate expression of this approach to date. There is, quite literally, a stream running through it, and at the centre – if you stretch the whole thing out – is a sort of Creator god, kneeling in the water while from his head burst all manner of terrible things: sinewy ribbons, skeletal harpies, twisted roots sprouting human organs, Death itself. It is a bewildering mash-up of myths and ideas: there are Aleister Crowley symbols, and beautiful flowers, and bursting pomegranates. The title is Greek and refers to the Platonic idea of the ‘world soul’ – the idea that the physical world is a single living entity of which all entities are related parts – but the Creator in the water comes from the Indian origin story of Prajapati and the piece is bookended by quotations from Robert Calasso’s classic study of Hindu mythology, Ka.

Anima Mundi’s book format prompts you into searching for a story. When I suggest this is misleading, Lane insists that there is a narrative, albeit a ‘very open one’. There is a sort of beginning and end. It opens with a homage to Gustave Dore’s image of Charon, the boatman of the Ancient Greek underworld, and, after the chaos of the central pages, ends with another image of still water: a skull gazes across over an infinity symbol swirling in the waves, ‘asking you’ as Lane puts it, ‘to see the piece as a cyclical, perpetual journey.’ It is, in essence, a vivid dream about creation, sex and death.

I ask Lane if he dwells much on his own mortality (stupid question…who doesn’t?). ‘I think to be reminded that you are going to die someday is a very grounding thought’ he says. ‘And rather than being morbid, I see it in the Memento Mori tradition: it should remind you to live while you’re here.’

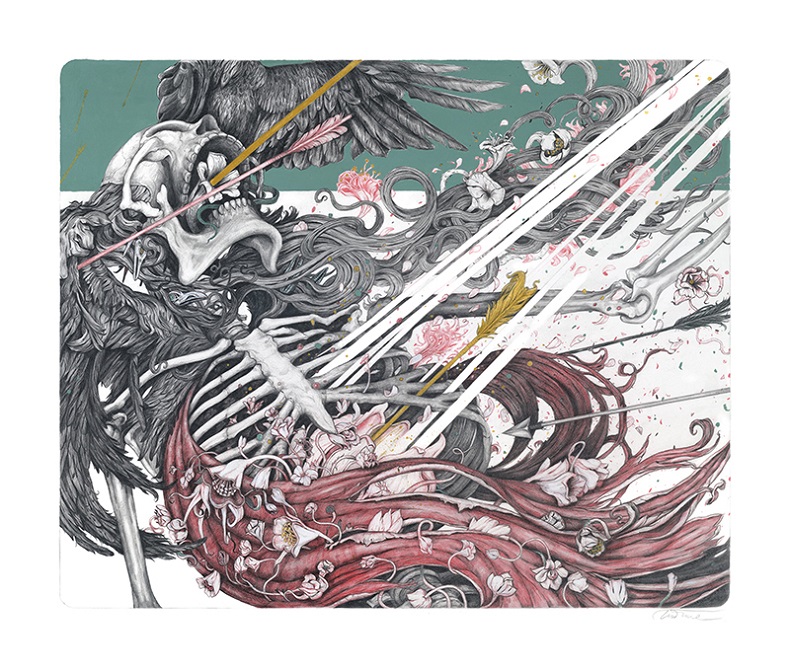

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Lane’s work is the combination of the grotesque and the beautiful. A case in point is Crepuscular Arrows [above] a large drawing accompanying the Anima Mundi exhibition. It is fairly gruesome body horror, yet in its composition, with the skull, the flowers and the streaming light, it is strongly reminiscent of the ‘vanitas’ still life tradition (see for example, paintings by Cezanne or van Utrecht). I ask Lane if he aims to create beauty in his art, and he seems genuinely stumped by the question. Later, by email, he refers to a quote by Norman Lindsay, which he says encapsulates his method: I don’t work out my pictures on an intellectual formula. I let the picture evolve as an image in my mind and put it into pictorial form, and then find out afterwards what it means. Which is merely to say, that, as an artist, I think, in forms, which later I translate into words.

Lane explains that in Anima Mundi’s conceptual stages there was in fact a proper story about a modern day Venetian gondolier who is transported to the underworld to take Charon’s place on the river Styx. This was developed in conjunction with New York horror writer Nicholaus Patnaude, but later abandoned when Lane ‘went off on his own creative tangent’. His accomplishments as an illustrator mean that people do want to work with him, but Lane admits that he is not a ‘team player’ when it comes to his drawing. Like most of the best artists, he is driven purely by his own vision, with little interest in catering for an audience or, indeed, in collaboration. Ultimately, he draws what he wants to draw, for himself. What he cares about is, in his words, ‘being in your own world as an artist and expressing your own peculiar world view’.

This is heartening. There is a lot of negativity about the state of the creative arts at the moment, not without some justification. Will Self recently penned a fine polemic against the colonisation of culture by hollow hipsterism (the totalising capability of dickheads + web = an assumed equivalence between all remotely creative forms of endeavour. Nowadays someone who sticks old agricultural implements on the wall of a Los Angeles motel regards himself as on a par with Michelangelo; moreover, since all their friends are dickheads, too, no one is about to disabuse them.)

But pessimists overlook the great benefits the web has brought for art. Crowdfunding sites enable artists to do exactly what they want for their own art’s sake, and find their natural, niche audiences without worrying about being widely commercial. People like Jack Gibbon – the spindly, genial director of the Antlers gallery – help. Gibbon has a keen eye for technically skilled, interesting artists who deserve a showcase, and I think his Antlers project is a tremendous good in the world. On my way out Gibbon handed over my copy of Anima Mundi in a shiny golden packet and I headed back into the blazing heat and the gigantic Bristol traffic jam, impatient to get home and start playing with the folding, interlocking, morbid contents of Tim Lane’s peculiar creative mind.

I like it – the foldy mechanisms and strange bodyshock imagery make me think that this chap would make a perfect illustrator of Clive Barker stories

There is a lot of negativity about the state of the creative arts at the moment. What goes around comes around, Marcel Duchamp, he of the Thos Crapper ‘sculpture’ railed against art, the commercialisation thereof, developed a pet lip and sulked in America, declaring a silence about art. Joseph Beuys, a kraut, joined the Fluxus movement, set up by George Maciunas to take the piss out of art, Beuys then railed against Fluxus, “too commercial, meine freunde” he said, at one of his famous documenta, then left. Beuys, more shaman than artist (he was an acolyte of Rudolf Steiner, a right nutter) railed again, this time against the Crapper man “the silence of Marcel Duchamp is overrated” he said, declaring that everyone is an artist, a wonderful counter to the commercialisation of art. He may have had a point.

Tim Lane reminds me of Charles Avery, painting meets story, both are fine draughtsmen, Avery’s stories more weird, Beuys was an original, he didn’t think out of the box, he was never in one, left a marvellous work of art in the public domain, Kassel’s 7000 oaks.

Beuys is an odd one — he was obviously at least part charlatan but there’s something genuinely unheimlich about some of his stunts, something you could never say about 90% of the conceptual/performance/neo-Dadaist pap that swirls around the contemporary art world.

Do you have an opinion about Anselm Kiefer, Malty? I’d be very interested to hear it. Reckon I might have to go along to the Royal Academy and take a look.

I think I like the Tim Lane; at times it looks rather like cover art for a lost Grateful Dead album

(not necessarily a bad thing).

Jonathan, saw the Kiefer exhibition at the Wallraf’s Koblenz outpost, he may have something to say, but exactly what is beyond my pay grade, confronting das elephant in the room is a big can of worms for German Artists, Beuys was a Stuka pilot and, as such, would have been personally responsible for the death of many people, it messed with his head and it showed. Gerhard Richter was a youngster then and has very raw memories, his over painted photographs of Tante Marianne and Onkel Rudi kind of say it all, they are a haunting requiem. Kiefer was a southern Baden-Württemberger, an area passed by, by time, the ancient aunt of a friend, from north of Freiburg, once said, war, what war? So, the source of his quest…the elephant in the room, comes from what I wonder, becoming indignant?. All three artists are connected, although Richter, now living in the Hahnwald, that upmarket suburb of Köln, when asked about Beuys, simply peers over his glasses and smiles, Beuys seems not to have made mention of Keifer.

It seemed odd to me that it was the Wallraf who staged the exhibition, modernism being not really their cup of tea, the Ludswigs does the modern stuff, in a big way, do they , who have within their walls, amongst many others, a magnificent Beckmann collection, Two sublime Paula Modersohn-Becker’s and Dali’s Perpignan Station, perhaps sense a dud?