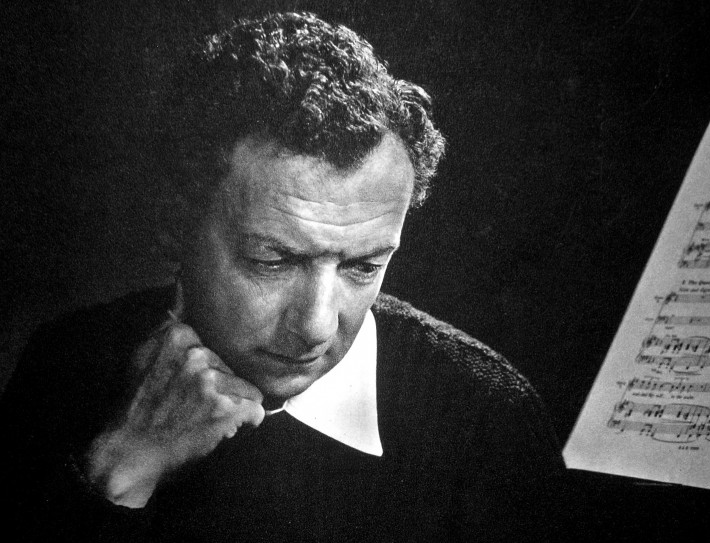

Returning to the new-look Dabbler, Mahlerman turns his attention to Benjamin Britten and shares his personal attachment to the greatest English composer since Purcell…

Had he not lived in Restoration England, where fully-composed opera was not yet accepted, there is little doubt that Henry Purcell would have developed into the great operatic composer many, even today, believe him to have been. But this undoubted genius liked a drink and, one evening, his wife Frances locked him out of his own house in Westminster, and the chill (or perhaps TB) that followed his night on the tiles finished him, aged about 36 – a loss to music that ranks alongside the death of Franz Schubert just over 100 years later.

Aside from his wonderful melodic gifts and his vividly dramatic imagination, he had a profound understanding of the human voice, and a skill in setting English words to music that has perhaps never been equalled – until the arrival of Benjamin Britten, born just before the Great War. To Britten, and for that matter his near contemporary Michael Tippett, Purcell was an idolized foster-father, and you don’t have to wander too far in Britten’s vast neoclassical oeuvre, to find the fingerprints of the 17th Century master.

In 1695, the last year of his life, Purcell produced the ten movements of the incidental music to Abdelazer, or The Moor’s Revenge, itself an adaptation of the tragedy from 1600, Lust’s Dominion – and as WW2 was ending, the 32 year old Britten boldly appropriated the second movement Rondeau from this suite and began work on his Opus 34, the Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Purcell, that became better known as The Young Person’s Guide To The Orchestra. Like many others I’m sure, this wonderful piece was my introduction to Britten’s highly individual soundworld, and I vividly remember being almost sick with excitement when the triumphant final Fugue started, shifting from minor to major in the last few pages. Here, any suggestion that the Berlin Philharmoniker is not the greatest orchestra on the planet, are put firmly to bed.

Five years earlier at the start of the war, the pacifist Britten was in America considering a return to England when, curiously, he received a commission from the government of Japan, for a piece to celebrate the founding of the Japanese empire (why Britten I wonder?). The commission was accepted and delivered – but rejected by Emperor Hirohito, who considered the ‘Christian’ titles, and bleak content, an insult. The purely orchestral Sinfonia da Requiem is indeed one of the most harrowing pieces in the composer’s output, but stands as an extraordinary achievement for a 27 year old. The Lacrymosa first movement is a funeral march of unremitting blackness, and the mood is rarely lightened in the following Dies Irae and final Requiem aeternam. The nod to Tchaikovsky in the Young Person’s Guide is not particularly obvious; the debt to Gustav Mahler, one of Britten’s favourite composers, is clear on every page of this amazing score. The scratchy film of Hermann Goring and the other bad-boys at Nuremberg, post-dates the music by about five years.

In the run-up to the first and second performances of Britten’s War Requiem in May 1962, my interest in ‘serious’ music was embryonic, shall we say. I had met Ornette Coleman at Birmingham Town Hall, I had seen the Everly Brothers at the Opposite Lock, and I had heard Dylan, also in Birmingham, draining the National Grid, and driving the Folkies to distraction. I’d also dropped my sister at the Coventry Hippodrome to see the Beatles, and gone there with my mum, who wanted to see a very young Tom Jones – and yes, they did throw knickers at him from the balcony. I suppose you could say that I had, in a dull post-war Midlands City, an exposure to quite a number of musical influences.

I played violin in a number of youth orchestras, and I could sing a bit – or thought I could. One of the orchestras was run by a brilliant organist who, in 1961 became the first organist and choirmaster of the new Coventry Cathedral. David Lepine (who was later engaged to the novelist Susan Hill, but whose heart stopped beating in 1972, when he was just 43) was casting around for good boys’ voices to sing in the treble chorus at the looming premiere and, probably pushed forward by my mother, I sleepwalked into an audition. It took Lepine less that a minute to spot the lack of quality in my voice, but the pearl in the cow-pat, for me at least, was a place at the first performance of the Requiem, and the second – and on the day before the premiere, I heard the first performance of Michael Tippett’s King Priam, the musical language of which was a bit too advanced for my young ears.

My musical God was Dimitri Shostakovich and, a decade later he was in Dublin with his wife, collecting a doctorate from Trinity College and attending a concert in St Patrick’s Cathedral, at which I met him, briefly. He was very ill at this point with the cancer that, three years later, would end his life, and one of the pieces played at the concert was by Britten, his Serenade Opus 31 for Tenor, Horn & Strings. I didn’t know then, but have learned since of the close personal friendship that existed between the two composers, and the love and respect they both had for each other’s music – and it seems that the Opus 31 was the Russian master’s favourite piece of Britten’s music.

It is cast in six movements that are enclosed by a horn-solo Prologue and off-stage horn-solo Epilogue. The broad theme, as in the Requiem above, is darkness – evening, night and the approach of sleep. Here is the last sung movement Sonnet, to words by John Keats ‘O soft embalmer of the still midnight’. In performance this movement is ‘used’ by the horn player to remove himself from the stage to a distant spot in preparation for playing the solo Epilogue that concludes the piece. Britten’s sense of theatre never deserted him.

Although it is slowly starting to appear in the concert hall, the Violin Concerto Opus 15 was hardly played anywhere until the very end of the last century. This is something of a mystery. It has all the cool beauty of the Alban Berg (the first performance of which Britten attended, reporting afterwards that he found it ‘just shattering – very simple and touching’), some of the elegiac quality of the William Walton, and all the restless intensity of the first concerto by Shostakovich; the concerto by Jean Sibelius from 1904 towers over everything, including the Elgar. The intensity present in this concerto grips the listener from the very first bars of the opening movement, and the clenched-fist stays locked until the contemplative close of the third movement Passacaglia, the last pages of which we can hear on this video of the Russian virtuoso Maxim Vengerov. Britten used the passacaglia form seriously for the first time in this movement and, both he and Shostakovich employed it extensively for the rest of their lives, as it usefully indicates a ritualized mourning, an aural atmosphere that both composers revelled in. When they employed the passacaglia form, graveness was never far away.

Marvellous post Mr Mahlerman and how wonderful that you met one of my musical gods – Shostakovich!

I’m not convinced that Britten is the greatest English composer since Purcell, but his earlier works like the Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings are sublime. I can’t help feeling that the later Britten didn’t quite fulfill the promise of his youth (with the exception of his masterly final string quartet).

Großbrittennien indeed, Mahlerman and to have been in his presence…..Britten has been an integral part of what must be three of the most subliminal moments in the musical life of the post war period. Two are well documented and can be enjoyed at leisure, The re-consecration of Coventry Cathedral and the War requiem, an historical and moving occasion. The second is the utterly sublime Mistislav Rostropovich and Benjamin Britten arpergione, two performers in perfect harmony and, miraculously, some film footage remains of the St Petersburg recording of the Schubert sonata, originally written for an instrument that was as popular as an Austin Allegro, tuned like a guitar, sounded like a vacuum cleaner on crystal meth.

The third, and most poignant was that day in January 1952 and the performance of the Abraham and Isaac canticle, Kathleen Ferrier dying of cancer and in increasing pain (although she was shortly to fly to Vienna and make the legendary Das Lied von der Erde recording) and her friends aware of her condition, the church setting, the haunting music, we can only dream, and weep.

The delayed publication of this ‘Lazy Sunday’ post (If it was delayed?) has been well worth the wait. Wonderful music; fascinating insights. Is it ‘Editorial’ rather than you, MM, claiming Big Ben was the greatest since Purcell? I can’t find it in the text.

My love of a good deal of Vaughan Williams’ vast and glorious output instinctively leads me to support any claim that RVW was the finest English composer since Purcell, but I recognise that instinctiveness is a poor tool to use in measuring relative greatness. I’ll leave it to others with far more profound musical knowledge to apply criteria that gets closer to the heart of the matter.

I’ve often wondered why Britten, a composer of outstanding orchestral music, didn’t apply his talents to the symphony; based on what he gave us, can you imagine how profound and moving a BB funeral march might have been? Come to think of it, how joyous a ‘little symphony’ a la Beethoven 8, might have been?

He was a bitchy sod, wasn’t he? But aren’t they all. Even RVW, who described Mahler as ‘a very tolerable imitation of a composer.’ But Ben seemed in a class of his own. This from Michael Kennedy:

‘When he had first heard Walton’s Viola Concerto in 1929 he thought it ‘stood out as a work of genius’. But this enthusiasm soon cooled as he realised that Walton would be his chief rival for the position of ‘white hope of English music’. For the rest of his life, Britten swung between hot and cold where Walton was concerned (Walton had a similar attitude to Britten and his music).

Britten in 1971 on Richard Strauss, referring to Der Rosenkavalier as ‘that loathsome opera, which makes me almost physically sick to hear it’. Britten could dish out criticism but even as a mature adult he had such a thin skin where his own works were concerned that he resorted to the cowardly ploy of tearing up any offending letter and returning the shreds to the sender. Another unpleasant facet of his weak character was his ruthless way of terminating friendships if things were not going his way. The soprano Sophie Wyss, the tenor Robert Tear, the conductor Charles Mackerras, the librettist Eric Crozier and many others joined the ranks of ‘Ben’s corpses’. Banishment was usually for life. The more one learns of Britten the man, the less one warms to him. But his music — that is something else!’

That was Editorial overstatement, I fear. I possibly overinterpreted the line ” a skill in setting English words to music that has perhaps never been equalled – until the arrival of Benjamin Britten”.

Apols to the poor benighted author as ever, but at least it got you talking!

There is a strong connection ‘twixt Benjamin Britten and Henry Purcell (and Noel Paton) Britten conducted The Fairy Queen with, among others, the splendid Jennifer Vyvyan and Owen Brannigan. The Decca CD includes the cover art from Noel Patons glorious Reconciliation of Oberon and Titania. This version of the opera includes a glorious Now the night is chas’d away

Yes JH, he was rather a sour individual – but a composer of genius I think. My favourite quote from him was when he was conducting a chorus of ladies and, typically, singled-out one poor soul for a lashing, with ‘If that’s the best you can do, you had better go on doing it’. What a sweetheart! RVW runs him very close, and is much more of a revolutionary than he is ever given credit for, Walton simply didn’t write enough that was first class, and Elgar….well, all that Brahmsian Imperialism gets a bit tiring I feel.

I have the utmost respect for your opinions, MM! My own tastes place RVW in front of BB; those nine symphonies are of a staggeringly consistent, and very high, quality. What about Ben’s operas, I hear you roar: “Hugh the bloody Drover doesn’t get anywhere near.” No, maybe not, but what about Riders to the Sea? Stop laughing, MM! Movements one to three of Walton’s first symphony never fail to stir me to the view that this is just one outstanding movement short of being the greatest symphony of the 20th Century! You’re laughing again, MM………..

I also think that RVW is the greatest English composer – from the Tallis Fantasia to the extraordinary 9th Symphony. Only the Sea Symphony leaves me cold. As for Walton, I think it’s really the sublime first movement that makes the 1st Symphony. I could take or leave the rest of it. If he’d published it as a one-movement symphony, like Roy Harris’s 3rd, I’m sure it would be a masterpiece.