In this dispatch, Rita explains how the 19th Century poet was responsible for the whole course of her life…

If there were one person I could hold responsible for the twist of fate that sent me to live in America, it would have to be Gerard Manley Hopkins. Yes, the Jesuit poet who lived and died in the century before I was born played a crucial role in my life. If Father Hopkins were to know that in the 21st century a woman would write these words he could hardly be more surprised than at the fact he was known to posterity as a poet at all. For it wasn’t until 1918, long after his death, that his friend Robert Bridges published a collection of his poems. And fifty years later the ecstatic poem of the glory of God revealed in nature, God’s Grandeur, would prove a fulcrum in the life of a young English woman.

I first studied the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins in the sixth form at my convent school as part of the curriculum for English A Levels. A Jesuit poet was a natural fit for a Catholic school education, though of course there was no mention of the homoerotic undertones so significant to later biographers. The passionate intensity of Hopkins’ love of God and love of nature certainly spoke to the burning emotions of adolescent girls, while the complexity of his language and innovative “sprung rhythm” appealed to the budding intellectuals we imagined ourselves to be. As sufferers of teenage angst we could ennoble our typical emotions by identifying with Hopkins’ frequent spiritual depressions, his dark nights of the soul, described with excruciating anguish in such poems as No Worst, There Is None:

O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall

Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed.

Most convent schoolgirls go through a phase of wanting to be a nun and I was no exception. We thrilled to the romantic words of The Habit of Perfection, a hymn to the cloistered life describing the clothing ceremony of a nun as a wedding:

… Poverty, be thou the bride

And now the marriage feast begun,

And lily-coloured clothes provide

Your spouse …

As things turned out Father Hopkins would bring me romance of a more worldly kind. While two of my best friends actually did become nuns, I headed off to the University of Sussex. Sussex at the height of the “swinging sixties” could hardly have been a greater contrast with my sheltered convent school background. I was to go through many changes, but something that did not change was my devotion to Gerard Manley Hopkins.

It was on one of those typical heady university evenings of sitting up late arguing philosophy and discussing poetry that the crucial moment arrived. One of the students gathered in my bedsit was an American I knew slightly. He had joined the group of my friends who hung out at the Catholic Chaplaincy. The talk turned to poetry, the name Gerard Manley Hopkins came up, and suddenly there we were, the American and I, reciting God’s Grandeur in unison from beginning to end. It was a classic “across a crowded room” moment. Our eyes met, everyone else fell silent, and Father Hopkins cast his spell upon us. As we recited the last words, “ah! bright wings,” with exactly the same ecstatic cadence, I knew I had met my soul mate. For each of us, we were the first other person we had met who could recite whole chunks of Hopkins word for word. Even from such notoriously difficult poems as The Windhover and The Wreck of the Deutschland. The American was even more surprised than I for he didn’t know Hopkins was taught in school any more. He learned the poetry from his Jesuit educated father and thought of it as his own personal esoteric knowledge. (Some years later he was to read Hopkins’ eulogy Felix Randal at his father’s funeral).

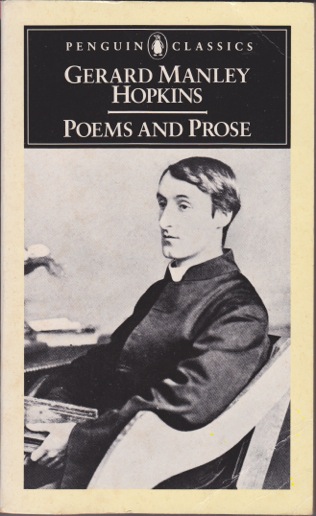

Well, from that moment everything else followed with the inevitability of fate. I found myself traveling to America with just $200 to my name, all my worldly goods tucked into a single rucksack, a few paperbacks to sustain me on the journey, including my precious Penguin copy of Gerard Manley Hopkins: Poems and Prose. We were married in Berkeley by a Dominican priest we had met at the Sussex Catholic Chaplaincy. A move to Washington D.C. and two children followed. Real life crowded out communing with Gerard Manley Hopkins.

Before I reach the end of the story, I must digress to tell the most marvelous Hopkins moment of my adult life. One of my visits home coincided with a Hopkins exhibit in the public library at Stratford where he was born. Stratford is quite near where I grew up in Essex, but I knew it only as a station on the branch line into London. By a remarkable coincidence, Hopkins’ birthplace is also where the German nuns who drowned in the 1875 shipwreck that inspired The Wreck of the Deutschland are buried. The nuns were en route to America to found a Catholic school when the ship ran aground off the east coast of England. Little did they know that their deaths would inspire one of the greatest poems ever written; a magnificent, engulfing wave of a poem considered too strange and difficult for publication at the time. It is hard to single out one stanza to represent the whole, but here goes:

Into the snows she sweeps,

Hurling the haven behind,

The Deutschland, on Sunday; and so the sky keeps,

For the infinite air is unkind,

And the sea flint-flake, black-backed in the regular blow,

Sitting Eastnortheast, in cursed quarter, the wind;

Wiry and white-fiery and whirlwind-swivelled snow

Spins to the widow-making, unchilding, unfathering deeps.

My brother and I decided to make a pilgrimage to the Hopkins exhibit and visit St. Patrick Cemetery to find the nuns’ graves. It was a typical gloomy, grey London day, perfect weather to wander a graveyard. We wandered for quite some time, finally realizing it was going to be next to impossible to find the graves in the vast, sprawling, rather unkempt cemetery. We decided to ask for directions at the office by the entry gates but it was closed. Trailing back down the path and about to give up we caught sight of a group of gravediggers leaning on their spades in the manner of English workmen taking a break between tea breaks. It was a classic scene in the otherwise deserted cemetery: I expected to see one of them hold up poor Yorick’s skull at any moment. “Well let’s ask them,” I suggested to my brother, though I was doubtful the humble gravediggers would be familiar with the works of Gerard Manley Hopkins. I approached them and began a rather awkward, rambling question. “Excuse me, we’re looking for some graves, there was this famous poet, and he wrote a poem about a shipwreck, and …” I sounded more and more embarrassingly pretentious to my own ears. Finally one of the men interrupted and put me out of my misery. “Ow,” he said in broad Cockney, “Yer mean them nuns wot drahn’d?” He proceeded to give us perfect directions and soon we were standing by a nondescript grave marker, almost obscured by overgrown weeds. It was a bit of an anticlimax after our encounter with the gravediggers from Central Casting who disappeared as suddenly as they had appeared. Maybe they were the ghosts of the very men who dug the nuns’ graves back in 1875?

Now I must reveal a truth I have learned since that naïve and idealistic young English girl gazed into a stranger’s eyes and bonded over poetry. It turns out that a mutual devotion to Gerard Manley Hopkins is not sufficient foundation to sustain a marriage. During the drama that accompanied our breakup I hurled the worst possible insult I could think of at the other woman: “She’s probably never even heard of Gerard Manley Hopkins!” Indeed she had not, and nor had my present husband, to whom I have been married for close to thirty years.

So Father Hopkins, for better or worse you did determine the course of my whole life, but I’ve never regretted my love affair with you. Requiescat in Pace.

Great story, Rita – and certainly a highbrow way to meet a spouse!

Thanks Rita.

Apparently he was nicknamed ‘Manley’ because he was so butch, metaphysical poetry being the cage-fighting of the Victorian era. When one of the ladies accidentally exposed an ankle, Gerard was always one of the last to faint .

Hopkins left a rather slim body of work; the edition we have (which includes selected letters also) will slide under all or most of the bedroom doors in our house. Would a relationship based someone who got longer to write–Byron or Browning or Wordsworth–have had more staying power?

Bravo Rita…….which sounds like a coded semaphore from a WW2 bomber pilot!

On further consideration: http://dc20011.blogspot.com/2014/02/books.html