This week, a slang lexicographer’s delight: the autobiography of a 19th century villain that contains a goldmine of criminal language…

Like its standard, literary equivalent, the literature of slang has its canon and its classics. I have mentioned some of the greats – Taylor the Water Poet, George Ade, Surtees, Wodehouse – but some, for whatever reason, have slipped between the cracks. I would love, for instance, to introduce Dabblers to Helen Green (whom I yearn to have been a relation but know it to be impossible: however my grandfather’s name appeared, I assume it was not as that verdant monosyllable) but of her we know nothing. Only that she was a New York journalist and produced two egregious volumes – At The Actors’ Boarding House (1906), and The Maison de Shine (1908) – centred on the world of show-business digs lower Broadway-style, full of small-timers, con-artists and blithely guiltless consumers of morph and hop, and Mr Jackson (1909), another work with a satisfying disdain for conventional moralising.

Of a production of half a century earlier, we know a little more, which we must since it was a purported autobiography. Leaves from the Diary of a Celebrated Thief and Pickpocket was serialised in the National Police Gazette, New York’s answer to the Bell’s Life, in 1863-4 and then published in book form. Leaves is more a detailed memoir than a diary as such, and its breathless subtitle, ‘Incidents, Hairsbreadth Escapes and Remarkable Adventures’ was presumably a sub-editor’s embellishment. There are, as far as can be ascertained, but two extant copies of the book. Both reside on microfilm, one in the British Library, one in the Library of Congress.

Leaves has slipped through most researchers’ searching fingers. It eluded Eric Partridge, whose Dictionary of the Underworld would surely have feasted on its hundreds of possible citations, many of them of words hitherto unlisted. It is unmentioned by those two modern cataloguers of the 19th century New York underworld Irving Lewis Allen (The City in Slang 1993) and Luc Sante (Low Life, 1992) and indeed by Herbert Asbury, on whose Gangs of New York (1927) both of them draw. These latter omissions are perhaps understandable: Leaves may have been published in the States, but is a British story set against ‘work’ in a variety of British locations (London, Scotland, Yorkshire) and occasionally northern France. If the anonymous author was active in New York, he isn’t talking.

Why a European villain had to travel to New York to get published remains a mystery. According to Professor Gerald Cohen of the University of Missouri-Rolla, seemingly the first scholar to take note of the book, what seems to have happened is that this mid-19th century villain, a veteran of the British crime scene, finally fled his native land, where things had become distinctly ‘hot’. He pitched up in New York and for a while continued much as before. But here too he became known. As Professor Cohen puts it, ‘At some point he wanted to go straight, but what sort of employment could he find, when all his past professional activities had centred around stealing? Solution: write his memoirs for the National Police Gazette, but without revealing his identity.’ This last point is undoubtedly correct: there is only one hint at the author’s name in the text, and no guarantee that even that is true.

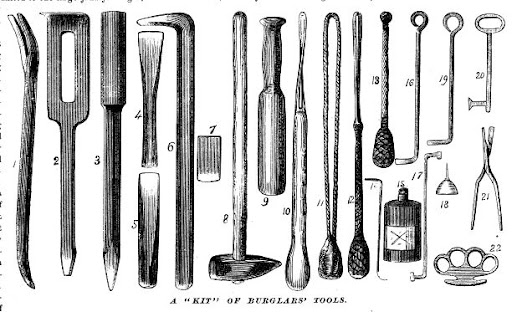

Leaves is quite as fascinating and as dense in criminal language as anything ever published. It seems, unlike some of the modern ‘hard man’ memoirists who hymn their years of criminality in terms that seem to owe more to the film script they hope to sell than to their actual speech patterns, absolutely without artifice. The use of contemporary cant appears unselfconscious – or as unselfconscious as it can be when every single instance is bookended with a pair of apostrophes. But these soon vanish into the background: this, surely, is how our Burglar spoke. As for the ‘incidents and adventures’, they are undoubtedly there, albeit a little repetitive, as are the ‘escapes’, even if the Burglar and ‘Joe’, his main confederate do serve a few months in jail. What matters, at least to the lexicographer, is of course the vocabulary.

There are well over one thousand terms on offer. Among them are these: Bartemy: a whore, from the edible ‘Bartemy dolls’ sold at Bartholemew Fair; bedstead bloomer, a chamberpot; bludgent (or bludgeat or bludget), a thug who works with a prostitute: she lures a victim into an alley; he beats and robs him; brocky (plus brocky-faced or brocky-mugged), ugly, from ‘brock’, a badger; the Cockney’s breakfast, of gin or brandy and soda; the wide criminal use of cross, as in dishonestly or dishonestly come by, with its extensions cross cop, a corrupt policeman, cross cove, a robber, cross crib or cross drum, a public house frequented by thieves, crossman, a confidence trickster, cross moll, a whore who robs her client, and cross mug, a villain, literally (one with a) ‘villainous face’. Dike, for lavatory occurs some 60 years before its next appearance, and that in a slang dictionary; the dipping duke is that hand (duke) with which one pick pockets, the goosing crib or slum are both brothels; a farewell sally is a draught of liquor, Jack-the-wrong-man is a policeman and the Land o’Cakes is Scotland. The lardbag, from its smoothness, is the skull, Mr Ferguson! means the coppers are coming; loosables is phlegm in the throat, nammous means to leave, from the backslang nammous!, someone (is coming)!, thus namaser is one who absconds or something, usually money, that has disappeared. The picking up lay involves posing as a prostitute but actually luring a victim into the hands of a male companion, who would beat and rob him; a pinching- do is an arrest, a pipemaker is a detective, he ‘pipes’ or looks at his target, scammery means drunk, shisevag is something worthless (an extension of the very common shise, useless, fake). A spark-fawney is a diamond ring and a ridge-super a gold watch. Splodger (rhymes with ‘codger’) is an old man, tingalaro an upright hand-organ, turper, presumably from ‘moral turpitude’ means a prostitute, can’t tell Q from a bed- wrench denotes stupidity and where the Irishman hid his shilling is the anus. All, one must assume, were common, if only in criminal circles. All, ‘dike’ is the single exception and that is hardly common, have vanished; this criminal vocabulary of 1865 might never have existed. Yet all thrived once, meant something, were real, ‘working’ words. A professional vocabulary, a jargon vital for mutual comprehension.

This book sounds intriguing JG, regarding shisevag/shise, do you think this has anything to do with the german scheisse?