Jonathon Green continues his slang tour of London by venturing into an area just off Bethnal Green Road known as the “worst street in London”…

So which was the worst street in London? Marked in the most stygian black (‘lowest class…occasional labourers, street sellers, loafers, criminals and semi-criminals’) on Charles Booth’s 1889 map of London poverty. Is it Campbell Bunk near Finsbury Park, Dorset Street off Commercial Road, Streatham High Road, Flower and Dean Street in Spitalfields, or even an anonymous but much vilified alleyway off Gray’s Inn Road? Every one a loser: dens of thieves, nests of whores, scabrous pubs crammed with cosh-carriers, fetid subterranean passages pullulating with rats, damp-ridden walls, leprous water closets, filth, violence, child abuse, police never approaching but for mob-handed, slumming toffs, evangelical Christians stamping out the few pleasures – drink, fags, bashing the wife – that one might enjoy. Hells on earth to be sure.

And then, if things weren’t bad enough, there’s a writer.

Arthur Morrison (1863–1945) had begun his professional life as a sports writer (boxing and bicycling) before moving on to fulltime work at The Globe in 1885. A year later he became a clerk to the Beaumont Trustees, a charitable trust that administered the People’s Palace – a philanthropically designed educational and cultural centre for the local community – in Mile End in the East End of London. Here he began writing a series entitled ‘Cockney Corners’ for the Palace’s magazine, the People’s Journal and it was these sketches that would lead him to further writings on the area. A short story ‘The Street’ was published by Macmillan’s in October 1891, followed by fourteen more tales of London’s most impoverished area, published in book form in 1894 by W.E. Henley (who was already working with John Farmer on their slang dictionary) as Tales of Mean Streets. (A phrase that he apparently coined). The book, with its unrelenting depiction of East End squalor and the violence, crime and desperation that it engendered, was a controversial success. Especially as regarded the story ‘Lizerunt’ (i.e. Liza Hunt), a young woman, once blithe and flirtatious, who is first beaten by her boyfriend and then forced by him into prostitution.

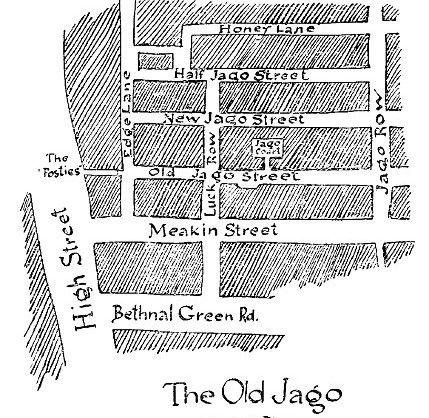

The book that made him, and proffered his personal candidate for ‘worst street’ was A Child of the Jago (1896). What he called the Jago was what its denizens knew as Old Nichol Street, the heart, along with its various tributaries in a square quarter-mile off Bethnal Green Road, of an especially gruesome slum. This story of the local street Arab, Dicky Perrott, laid out a succession of unmediated violence, criminality, dysfunctional family life and aggressive, fearful insularity. Drunkenness is a given. Despite the presence of a muscular Christian parson (Morrison’s portrait of the real-life Revd A. Osborne Jay, vicar of Holy Trinity, Shoreditch, and author of Life in Darkest London, 1891) Dicky cannot escape his environment and is fatally stabbed, refusing, as the Jago code demands, to ‘nark’ on his killer. In Morrison’s bleak portrait, death is the only escape the Jago will permit.

Slang, or at least cant, had always been used as colour for books which touched on crime. Morrison’s use is different; this is a story of working-class life and for a change it is the middle-classes who are allotted the cameos. Conversations are written phonetically, and the use of slang, criminal or otherwise, is common. But it has gradations. When Dicky slips, showing off, into the lexis of crime, his mother, not above profiting from her husband’s muggings herself, takes fright.

The boy returned to his box, and sat. Then he said, ‘I do n’t s’pose father ‘s ‘avin’ a sleep outside, eh ?’ The woman sat up with some show of energy. […] ‘No, I ain’t seen ‘im; I jist looked in the court.’ Then after a pause, ‘I ‘ope ‘e’s done a click,’ the boy said. His mother winced. ‘I dunno wot you mean, Dicky,’ she said, but falteringly. ‘You you ‘re gittin’ that low an’ — ‘

‘Wy, copped somethink, o’ course. Nicked somethink. You know.’ ‘If you say sich things as that I’ll tell ’im wot you say, an’ ’e’ pay you. We ain’t that sort o’ people, Dicky, you ought to know. I was alwis kep’ respectable an’ straight all my life, I ‘m sure, an’— ‘

‘I know. You said so before, to father — I ‘card: wen ‘e brought ‘ome that there yuller prop the necktie pin. Wy, where did ‘e git that? ‘E ain’t ‘ad a job for munse an’ munse; where ‘s the yannups come from wot ‘s bin for to pay the rent, an’ git the toke, an’ milk for Looey ? Think I dunno ? I ain’t a kid; I know.’

‘Dicky, Dicky! you must n’t say sich things !’ was all the mother could find to say, with tears in her slack eyes. ‘It ‘s wicked an’ an’ low. An’ you must alwis be respectable an’ straight, Dicky, an’ you’ll get on then.’

It is not the idea of crime – such is her husband’s ‘job’ and he ends up dangling on the gallows – but the criminal’s language that disturbs Hannah Perrott. It defies respectability, as of course does the whole of the Jago. Unlike the do-gooding but quite ineffectual missionaries of the ‘East End Elevation Mission and Pansophical Institute’, whom he duly mocks for their devotion to ‘the Higher Life, the Greater Thought , and the Wider Humanity […] with other radiant abstractions’, Morrison does not moralise: the entire text is infused with the deepest irony. But while the ‘street folk’ interviewed by the sociologist Henry Mayhew in London Labour and the London Poor had represented a world that was undoubtedly different to the readers’ own, it was, if only in casual encounters, one that they could at least see. Morrison’s Jago, is invisible to the average bourgeois; it represents social deviance, uncivilised savagery, something utterly and terrifyingly ‘other’. Other missionaries were posted to ‘darkest Africa’, the East End was also characterised as ‘dark’ and the ‘low’ language of its denizens as incomprehensible to the fascinated middle-classes as any tribal tongue.

A version of this post originally appeared on The Dabbler in October 2011.