Continuing his series about Phantom Libraries and unwritten books, Jonathan Law explores the books that only exist in dreams, and wonders why he once encountered one called Manly Ways to Eat Fruit…

There is something peculiarly painful about the idea of the lost or unwritten masterpiece – the great book that no one will read, ever, except perhaps in dreams. For writers, the thought may even involve a kind of terror, and it is hardly surprising if some have sought refuge in a particular kind of phantom library – the compensating library of dream. This might be defined as a semi-comic, semi-magical space in which the great lost works are somehow saved and restored. If nothing else, such a dream may serve as a consolation or psychic defence: a fire-proof Alexandria of the mind.

A key work here, in terms of its later influence, is James Branch Cabell’s Beyond Life (1919) – an odd fable that features a library of lost works to rival the Bibliothecha Abscondita of Sir Thomas Browne. In the story Cabell’s narrator pays a visit to one John Charteris, an author who has retired to a mysterious Colonial-era mansion in Virginia. Here, in the “queer library” full of “serried queer books”, Charteris is able to show him something astounding: “the cream of the unwritten books – the masterpieces that were planned and never carried through”. As well as works by the acknowledged greats – Milton’s planned epic on King Arthur, a complete version of Coleridge’s Christabel – there are wonderful unknown books by “persons who never published a line”. Other very familiar books appear in the “Intended Edition” – not in their published form, but as their authors always meant them to be. And perhaps most magically of all, there is a sub-library of books by wholly fictitious authors (The Complete Works of David Copperfield taking pride of place).

Although his visitor is suitably awed, Charteris points out that not all these works are everything we might have hoped. Milton’s King Arthur may be “quite his most readable performance”, but the unwritten sections of The Faerie Queene and The Canterbury Tales are frankly “beyond human patience”. Likewise, the completed Christabel – so tantalising and suggestive in its fragmented state – “falls off toward the end and becomes fearfully longwinded”.

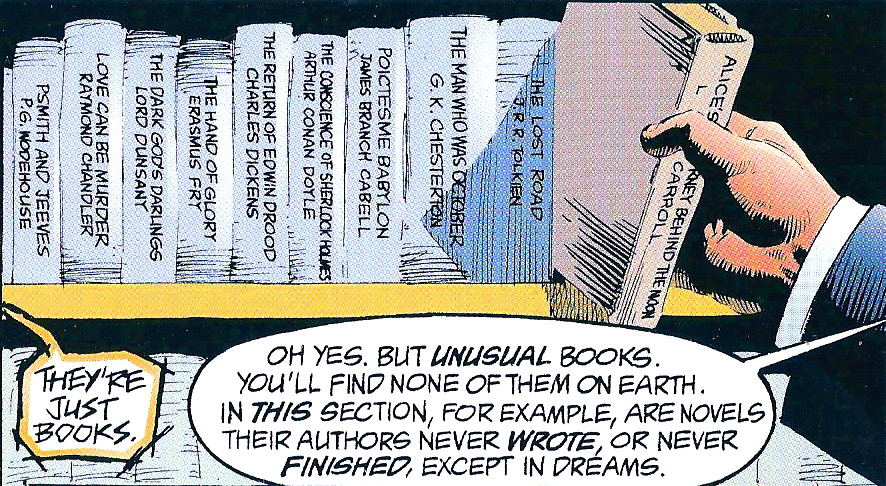

Although Beyond Life remains little read, at least in the UK, it has proved a particularly rich source for writers in the fantasy tradition. Terry Pratchett, for example, surely drew on Cabell when he conceived the library of Unseen University – a sort of quantum deposit library in which the initiated may find every book either written or conceived. A still more obvious homage can be found in the Sandman series of Neil Gaiman, where there is a lengthy account of the library kept by Dream – the god-like being who presides over all stories, dreams, and fantasies. This provides a last home for all those books that authors imagined but never managed to write: works blocked by drink, drugs, poverty, or simple indolence, not to mention madness, disease, and death. As well as a shelf-load of Coleridge, the library can boast such titles as The Return of Edwin Drood by Dickens, Tarzan in Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Swift’s The Last Voyage of Lemuel Gulliver, and Marlowe’s The Merrie Comedy of the Redemption of Dr Faustus. Other titles are more specific to the fantasy genre – Alice’s Journey Behind the Moon, The Fall of Gormenghast, Tolkien’s The Lost Road, C.S. Lewis’s The Emperor Over the Sea, T.H. White’s Arthur in Avalon. There is also that great perennial, The Bestselling Romantic Spy Thriller I Used To Think About On The Bus That Would Sell A Billion Copies And Mean I’d Never Have to Work Again by Anyone.

Through Gaiman, the influence of Cabell’s library extends to another extraordinary graphic work – the Black Dossier created by Alan Moore as a pendant to his League of Extraordinary Gentlemen series. The lost books miraculously restored in the Dossier include Faerie’s Fortunes Founded (1620), Shakespeare’s prequel to The Tempest; works of erotica by Fanny Hill and Pornosec, the porn-producing division of Orwell’s Ministry of Truth; and, perhaps most intriguingly, What Ho, Gods of the Abyss! (1928), a memoir in which “the famed English diarist” B. Wooster describes a run-in with the Abominable Ones of H.P. Lovecraft.

***

For several years now I’ve had recurring dreams of an imaginary bookshop set in the middle of a city, entered by a flight of stairs from street level and extending two or three floors below ground. It is ill-lit, dusty and labyrinthine, the best imaginable place for browsing, and I never fail to make unheard-of discoveries there among the ghostly stacks.

This is my Bibliotheca Abscondita, my bookshop of dreams.

So the Dabbler’s own Douglas Dalrymple, writing five or six years back at the New Psalmanazar – an incomparable blog now temporarily (one hopes) in abeyance. In a series of posts, Douglas went on to describe some of the treasures of his dream bookshop; wonderful, unheard-of volumes that would dignify the libraries of Thomas Browne or John Branch Cabell:

Seven Million Stray Dogs … The book is bound in curious triangular fashion and opens (impossibly) from two different sides … a universal almanac which I consult, in my dream, for Ikea-style instructions on assembling Italian Renaissance furniture pieces.

Cassseraghi … An early Italian opera libretto. The book is full of the most wonderful illustrations done in a style that somehow weds Watteau, Blake and early Picasso – harlequin figures emerge from velvety green shadows, highlighted in turquoise, red and shimmering gold leaf.

And perhaps most hauntingly of all, we are offered this – an interactive book that combines the functions of a search engine and a ouija board:

The Universal Register of Personal Opinion (URPO). This is a hardback volume with an erasable slate on the cover. Write your question – any question – there, then open the book to find answers from various living and historical figures … Close the book and write a different question on the cover and the contents are magically rearranged and updated. No single answer is definitive and contradictions will abound. Anachronism is more than half the fun since the book allows you to learn, for example, Cleopatra’s take on American health reform legislation, or Emily Dickinson’s opinion of Hammurabi’s personal hygiene.

Available from a dream bookshop near you.

***

As a rule I never dream of books, or libraries, or bookshops. But I did once, in my student days, and if there was ever a time to talk of this dream I suppose it must be now.

Anyone who knew Oxford in the 1980s will remember the slightly mysterious little shops that seemed to huddle among the thin streets between Jordan College and the back way into St Sepulchre’s churchyard. Perhaps they are still there, although it seems improbable. The shops were mysterious not so much in a Diagon Alley sort of way –although there could be a touch of that – but rather because you wondered how these dusty little places specializing in humidors or opera glasses or hairnets for men contrived to stay in business, even in a city as retro as Oxford. I remember a shop that sold nothing but Olde Worlde marmalades, each of which had, in its own way, a look of angry mud; another dealing in prayer books and devotional aids for one of the minor Orthodox churches; a third that stocked the most alarming pens – surgical-looking things that you could imagine playing the decisive role in some 1930s crime or spy caper. Even more disturbing, perhaps, were the small gents’ outfitters trading in styles that had not been worn without irony since the Abdication, not to mention strange male grooming devices whose purpose must have been obscure even then (you supposed that if they sold at all now, it must be to the devotees of some macabre sexual cult). Who indeed bought any of this stuff? Did these shops rely entirely on the custom of A.N. Wilson (frequently seen cycling by in ancient tweeds)? Or perhaps they did a thriving trade with the telly people sourcing stuff for the latest Agatha Christie or M.R. James?

There were also, of course, the bookshops; premises no less improbable than the rest, but with an additional quality of pathos and an almost sacred claustrophobia. Here rare antiquarian volumes – sometimes but not always sequestered in locked glass cases – shared space with piles of unsaleable, vintage tat that must have been picked up at a succession of desperate North Oxford house clearances. Some of these titles were: A Memoir of the Bicester Hunt, New Light on Philippians (by ‘Credens’), Every Man Under His Vine: or, The Case for Social Credit, On Foot in Rural Herts (by ‘Wayfarer’), A New Introduction to Theosophy, With Rod and Line on the Dorsetshire Frome, Uranian Longings (by ‘Ganymede’), Legends and Geology of Charnwood Forest, The Old Malvernian (1946), A History of the Mwele Expedition (5 vols.), Duck Hooks and Frenchies: Your Best Golfing Stories (by ‘Ten-finger Grip’), A Ravishment of Pomegranates by Lady Veronica Farfleton …

It was one of those days in late February or early March when sunlight is blown about the streets of the ancient city like smoke. (I am speaking now of my dream; we are somewhere in the dream). Feeling restless but strangely light at heart, I too let the wind take me into this neighbourhood of cramped streets, and through the door of the tiniest and most unfathomable of all the bookshops. As the bell banged behind me – but oddly made no sound – I told myself that I was looking for an edition of Cowper, perhaps, or Akenside; one of those charmingly dull 18th-century poets that no modern publisher will touch. I noticed that the shop was silent and empty (except for the stacked shelves and toppling ziggurats of books) and that the smell was not the familiar warm must but the odour of stone and puddled water.

I took a book from one of the shelves – it might have been Conversations with Nobody or perhaps How Rain Built the World – and discovered without surprise that the pages held words of my own; sentences and paragraphs from a five-year-old diary, the one I wrote after A Levels, in the dead summer of 1979. Of the Two Ways of Opening the Mouth and The Curator’s Lost Museum also seemed to be volumes of diaries – the journals I had failed to write when I was 10, 11, and 12. Yes, it was all here: forgotten childhood illnesses, with their mysterious secrets and bounties; the torpor of summer afternoons in school, when the collar of your shirt rasped like a noose and the dust-motes hung in the air like time suspended; friends, quarrels, picnics, uncles, birthdays.

I opened more books – The Epic of the Tattered Trousers, The Warlock of Palladia, The Kettle of Magnanimity, A General History of Ears – and found it was all the same story. Each described some phase or episode of my own life; most vaguely remembered, some blessedly not. The childhood holidays at Oban and Mother Ivy’s Bay; shameful, inexplicable failure in a maths exam; the trudge up a Welsh mountain to see a dull lake and a dribbling waterfall; a cricket bat, a chemistry set, a collection of rocks; the walk to the lone farm on the green moor, where a child lay very ill …

These books were puzzling and instructive and so – with a single exception – were the ten or twenty others I flipped open at random. The one I failed to make head or tail of was a scuffed, edgeworn thing called Manly Ways to Eat Fruit. This described a series of days and weeks in the life of a 50-year-old man – a mild sort of chap, going about his work, trying to placate his kids, and tearing his hair out over a bunch of things that made no sense at all. The book seemed at once so dull and so full of improbable lies that I closed it shut with a clap like thunder.

As I woke the elements of my dream were scattered like beads from a broken necklace – although for a while I could still see a few of them glinting and winking in odd corners, where they happened to catch the light.

In those days I did not believe in a Last Judgement, but the books in that weird shop gave me for the first time an inkling of what it might mean. When you are 23, life still seems vague and open; and I thought for a while about this dream and everything that it would change. I also noticed that it was spring now, with little scents and shadows in the margins of the day. I got up and got dressed and carried on precisely as before.

During the first of the Ashes test matches this summer – at Cardiff, England bowler Ben Stokes ate a banana in a most remarkable manner. He effectively ‘downed it in one’ – certainly it was the manliest eating of a piece of fruit I’ve ever had the good fortune to witness.

Wonderful short story to end on. ‘Angry mud’ is brilliant. Eerily accurate presentiment of being 50ish!