Rita returns to her ancestral Belgian homelands, and finds that the historical cities have succumbed to a plague of modern public art…

Martin McDonagh’s film In Bruges opened the 2008 Sundance Film Festival and went on to become a cult hit. The story of hapless Irish hit men stuck in the old Flemish town could have been dreamed up especially for my family, half Irish and half Flemish as we are. The film is quirky and funny and features famous actors, but the real star, everyone agrees, is the lovely medieval town of Bruges. There is just one problem with that. On a recent visit to Ghent, my mother’s hometown, my Flemish family claimed that much of In Bruges was actually filmed in Ghent.

The two towns have been rivals since at least 1382 when they fought the Battle of Beverhoutsveld, the final victorious showdown in Ghent’s rebellion against Louis II Count of Flanders. Today the rivalry takes a less bellicose, though nonetheless vehement, form. Why go to Bruges when Ghent has everything Bruges has and more? Beautiful medieval buildings, majestic towers, elegant bridges spanning the rivers and canals, a grim castle, and in the cathedral one of the greatest paintings in the history of art, Jan Van Eyck’s Adoration of the Mystic Lamb. And in addition to all this history Ghent is a vibrant modern city, not a museum piece like Bruges! This is the argument my husband heard on our previous visits whenever he mentioned he would like to go to Bruges. So this time I promised him we would go to Bruges for a day and he could judge for himself.

We boarded a crowded train in Ghent and joined the throngs of tourists who got off at Bruges and swarmed towards the historic town center. In the station plaza a large sign invited us to become citizens of Bruges, pointing the way to a train car-like passageway where tables along one side held application forms and pencils. The forms listed a series of questions about our hopes and dreams if we should become citizens of Bruges. On the opposite wall completed forms were displayed. My elderly aunt and uncle were setting a rapid pace and I didn’t want to get left behind. As I hurried through the passage one question and answer on the wall caught my eye: “What religion do you plan to follow in Bruges?” Answer: “The cult of Kim Jong Un.” Hmm. We walked on to our first destination, a place for followers of a more traditional religion. Bruges’s only Beguinage, a convent for nuns, is a group of small white houses and a church set about a central square. “Ghent has three Beguinages,” my uncle pointed out before we passed under the entry archway.

I remembered Bruges from a visit in my youth as a lovely old town with women in traditional dress sitting outside little shops demonstrating lace making. They were nowhere to be seen, and indeed would have nowhere to sit, as the streets were crammed wall to wall with jostling tourists and horse-drawn carriages. It was impossible to see the historic buildings properly amid the crowds and impossible to take a photo without capturing hordes of other photographers in the frame. There were so many people crushed onto the little arched bridges that I thought the old stones might finally give way and dump them all into the water. It did not take long for my husband to relent and agree that Ghent is far superior to Bruges. But we discovered that it wasn’t just the tourists; there was another modern plague infecting Bruges, the scourge of installation art.

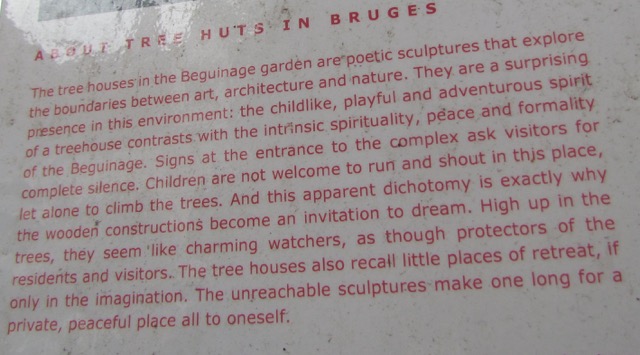

The first clue that something strange was going on came in the Beguinage. The central square was dotted with tall stately trees. Some of them had little wooden tree houses built high up in the branches. They were too small for a child, perhaps a hobbit? Or were they birdhouses? I could hear doves cooing from somewhere unseen. One of our group enquired in the gift shop and reported back that the proprietor, with a dramatic rolling of the eyes, said the tree houses were “art.” Then we noticed the sign.

We had stumbled into Triennale Brugge 2015, an art trail through the city that invited visitors to explore Bruges “as a living, growing and evolving organism.” According to the sign the artists…

…pose questions and reflect on the future and potential of the city, of urbanization, citizenship, lifestyle, community, economics, energy, space, sound and the values that guide us.

A mighty mandate. Perhaps Bruges was trying a little too hard to escape its reputation for being stuck in the past. We gazed back up at the Tree Huts, now with the knowledge that we were looking at art. But they still looked like crudely made wooden structures of no apparent purpose. The real art was in the accompanying text, which nevertheless omitted one key word from the lexicon of contemporary artspeak. We were not urged to “interrogate” the concept of the tree house.

In retrospect we realized that the citizenship invitation at the train station was the first stop on the art trail. Now on high alert for any more signs of art, we followed my aunt and uncle through the crowds towards the center of town. In the Market Square we admired the Diamondscope, a multi-faceted mirrored structure that reflected the belfry and other historic buildings in wavering, distorted images on all sides.

According to the text one Bruges citizen and one tourist were to enter the structure at a time, and in this enforced intimacy reflect upon the nature of the city. In practice, curious to see what was inside, multiple tourists crushed their way through the narrow door. I confess we did too. There was absolutely nothing inside and no time for reflection, just an urgency to push back through the incoming crowd to get some fresh air.

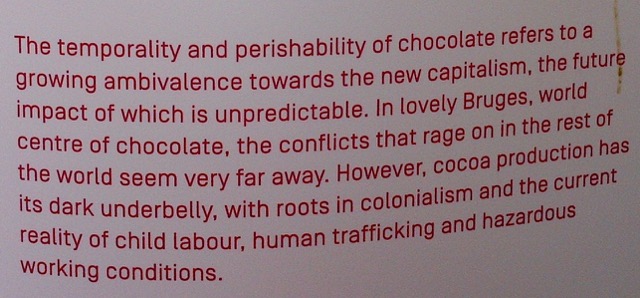

But our favorite exhibit, for its blend of absurdity and high-minded political discourse, was Uber Capitalism, a sculpture on the site of the medieval Huis ter Beurze, the first stock market in the world. A chocolate replica of the Beurze is topped by the rotating words “uber capitalism.” The perishable material:

recalls the darker aspects of the chocolate trade and expresses a growing ambivalence towards the seductive new face of capitalism in our time.

Surely the material couldn’t really be perishable; it would melt in the summer heat. But the slab of chocolate looked so real that, despite “do not touch” signs in four languages, people, including my usually law-abiding aunt, couldn’t resist poking at it to see if it was indeed chocolate. That was the question that seemed to be on most observers’ minds rather than reflection on the multiple connotations of the word “uber.”

The accompanying text portentously informed us that it refers to both the Nazi concept of the “Ubermensch” and the taxi company Uber. (A taxi strike protesting against competition from Uber was going on in Ghent at the time). The satisfaction of buying delicious Belgian chocolate from the nearby gift stores was undercut by reflection on “the dark underbelly” of cocoa production. On this disconcerting note we headed back to the train station. I am sorry to report that we missed the installations Gold Guides Me, Vertically Integrated Socialism, and Doing Nothing Doing. But as my uncle pointed out, why go to Bruges for modern art when Ghent has Belgium’s leading modern art museum, the Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst, known as S.M.A.K.

Back in Ghent, where the family was pleased to hear our negative verdict on Bruges, we came upon another unexpected art exhibit. Ghent is clearly determined not to be outdone by Bruges when it comes to installation art in public places. Gravensteen, the imposing Castle of the Counts of Flanders, is a grim fortress featuring the usual exhibits we expect in a medieval castle: suits of armor, swords and crossbows, a guillotine, and gruesome instruments of torture. But the horror is all at the safe remove of history, a place to take the children to make their history lessons come alive, a part of the imaginative landscape of childhood. But when we entered the first hall on the numbered route through the castle we were confronted with the life-size image of a dead body being lifted from a slab in a mortuary. Consulting the leaflet handed out at the ticket office we found we were viewing the first installation in an exhibit titled Departures:

This exhibition focuses on death, mourning, and saying goodbye to loved ones in very intimate, yet catastrophic circumstances … this is a gentle confrontation with death in a building steeped in history and aggression. In this dark palace of memories death is lurking…

What, we wondered, would a parent say to a young child who ran up the stone spiral stairs eager to see a suit of armor and was instead confronted with the graphic image of a dead body? This and other disturbing images in the exhibition were Victorian mortuary photographs. Among the other maudlin artworks were body masks made by draping sheets soaked in plaster over dead bodies, a death bed painting of the artist’s mother, and a photo of the embalmed body of a two year old girl who died of pneumonia. It was a relief to emerge from the stone enclosures of the castle, which had begun to feel like tombs, into the fresh air of the battlements. But still we could not escape reminders of death. Here were enlarged images of Tollund Man, the famous bog body dating to 350 B.C. Our leaflet helpfully explained that he was probably strung up as an offering to the gods. In one of the turret enclosures we were invited to sit on a stone bench and listen to a recording entitled Words and What they Are For, detailing everything the speaker wished he had said to his lover before death. The sonorous words were intoned in Flemish but according to the English translation in our leaflet it was just about as profound as a typical Facebook post about a failed relationship. The best part of the exhibit was an underground area that may once have been the dungeon. It was pitch dark except for eerie blue lights illuminating distant corners. A loudspeaker emitted spooky sounds and there were cries of alarm and giggles from the visitors. It was such a relief to be in a space with no images of dead bodies. But when we emerged into the light and I consulted the leaflet for the meaning of it all I found a poem by Dirk Brosse that ends with these lines:

with the last breath of life

every second absconds from the dial…

and the body returns to dust

to no-body

that’s all there is

We repaired to our favorite Ghent watering hole to wash away the stench of death with a few shots of jenever.

As we departed Ghent the city was preparing to be the backdrop of another film, this time playing itself, not Bruges. Workers were busy covering the ornate iron railings of St. Michael’s Bridge, built in 1910, with a false stone front for a TV film about the life of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor who was born in Ghent in 1500. Cruel and tyrannical in life, in death he is bringing another lucrative film project to the city.

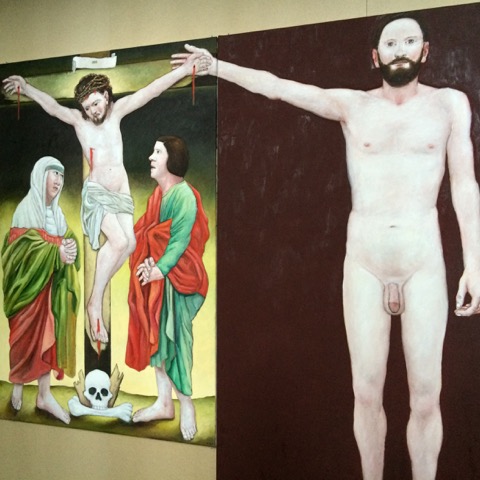

Our journey home took us through Reykjavik, Iceland where we found ourselves once more confronted with startling modern art, this time in the unlikely location of a church. Hallgrímskirkja, the main Lutheran Church of Iceland, is an arresting modern interpretation of the gothic with a heroic statue of Leifur Eiriksson dominating the entrance plaza and inside a gargantuan pipe organ weighing 25 tons. But much of the art in the church is a weird pairing of quasi-religious imagery with… ducks. Most confounding of all is this crucifixion scene. At first glance it may look like two paintings unfortunately juxtaposed, but look again and you see the hands nailed to the cross atop one another. One couldn’t help imagine the outrage if such a naked figure was displayed in an American church.

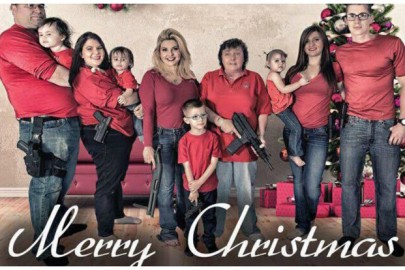

One thing I am happy to report from our travels: I only observed one instance of an American tourist who lived up to the stereotype of loud and crass. And that was in Bruges.

Many a hard working Briton has been seduced by the advertising and decamped to Bruges, a goodly proportion of the many will have availed themselves of Ryanair, landing in what most consider to be the south end of the Jura, therefore arriving in Bruges in bad fettle. The fettle is further soured after twenty four hours with the exclamation ‘is that it? and will you please remove that horse meat from under my nose’

Mmmm. Chocolate.

I found In Bruges a very powerful film – despite the laughs it’s drenched in mortal sin. That’s art. On the other hand, things that feel the need to provide self-justifying explanation usually emit no more than a squeak.

Cheeky Bruges – everyone know the world centre of chocolate is Bournville.

This post made me fanaticize about being an angry, rebellious street artist expressing his rage against the system by secretly interspersing modern public art with various versions of The Adoration of the Magi.