Is it possible to capture the essence of a place in a piece of music? Mahlerman examines some composers who tried…

In the early years of the 19th Century (certainly not before) the idea that the essence of a region or country, the weight of its social institutions and its most prominent features, could be expressed through its ethnic, inscribed music, began to gain some traction – this, against a backdrop of the invention of new musical instruments, and the rapid expansion of the 30-50 man (they were all men) classical orchestra into a body twice that size. The new palette offered composers, if they were devoted to the ideal of emotional or dramatic expressiveness, and possessed the imagination required, the means to create a completely new soundworld.

There are very few ‘modern’ composers, the durability of whose music this writer would care to place a bet upon, but the Hungarian Bela Bartok is one of them. A shy, retiring man of impressive, almost stubborn determination, he cared nothing for fame, fashion or personal influence, living almost exclusively inside his art, the central problem of which was the lifelong struggle to unite the melodies and rhythms of Magyar and east-European folk music with the harmonic and contrapuntal idiom of the central-European tradition.

It was not that he invented or quoted folk melodies, though once in a while that could happen – it was more that there is hardly a note of his music that is not impregnated with the feeling of the Hungarian melos – much of it discovered in his extensive travels with fellow composer Zoltan Kodaly throughout Slovakia, Romania – even Algeria, and making this frail yet explosively creative artist, not just a major 20th Century composer, but a devoted ethnomusicologist. He also managed to become a world-class piano virtuoso, a skill which was useful (as Rachmaninov discovered) when money was running short, as it often was. By way of expressing the magpie-qualities in his nature, here, from his early-middle period (1923), are the three, brief, final movements from the rarely heard Dance Suite, composed for a festival commemorating the merging of the two towns of Buda and Pest; they are 4) Molto tranquil 5) Comodo 6) Finale: Allegro , and are played here in a scratchy but totally idiomatic performance in 1952, by the LPO conducted by another great Hungarian, Georg Solti.

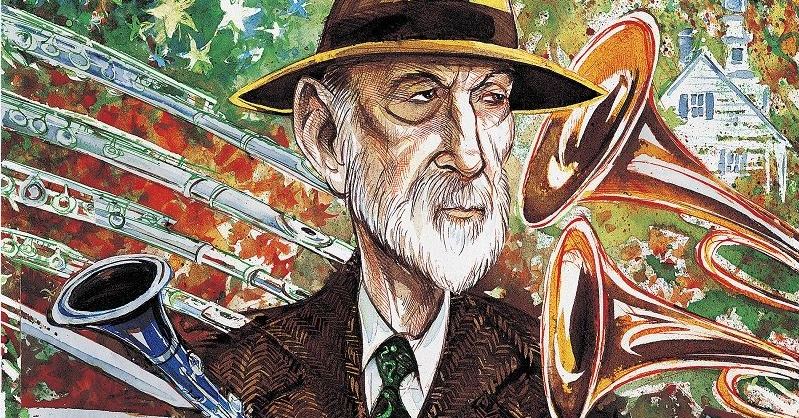

‘Roughly and in a half-spoken way’ – ‘The piano should be played as indistinctly as possible’ – ‘In a gradually excited way’. The traditional ‘language’ of classical music, the allegro con spirito and the andante con moto, was of little interest to the great American iconoclast Charles Ives [pictured at top], a pioneer in just about everything he turned his Yankee hand to, and the first national composer from that vast land-mass. The melos for Ives was a multi-faceted memory of village bands, town-hall meetings, and the sepia memories of Emersonian America. The ‘day job’, an insurance business that he started with his partner Julian Myrick, made him independently wealthy, but there was never much sign of wealth about his person or his home – he took just $25,000 a year in salary, and eschewed the fancy life that a man in his position could have adopted.

When he wasn’t working ‘at the office’ he could be spotted drifting around his house, often until the early hours, deep in compositional thought. But here was a composer who avoided the company of other musicians, hardly ever went to a concert, published his own music (because he could afford to), and refused royalties and copyrights……and yet, he was delving into atonality long before Schoenberg, into tone-clusters before Henry Cowell, and polytonality while Stravinsky was still dreaming. I would point dabblers toward the amazing Second Symphony to hear what the composer called his ‘soft’ music, infused as it is with the kaleidoscopic sounds of his memory – brass band numbers, hymn tunes, and popular folk songs such as ‘De Camptown Races’, ‘Turkey in the Straw’ and ‘Pig Town Fling’. This complex, multi-layered music ill-fits the dabbler format, and I have chosen in its stead a shorter, but no less ambitious piece which first appeared in 1908 when the composer was in his early thirties, The Unanswered Question is a study in contrasts. I can do no better than quote Ives’ own instructions on how this haunting piece should be performed.

The strings play ppp throughout with no change in tempo. They are to represent The Silences of the Druids who Know, See and Hear Nothing. The trumpet intones The Perennial Question of Existence, and states it in the same tone of voice each time. But the hunt for The Invisible Answer undertaken by the flutes and other human beings becomes gradually more active…..The Fighting Answerers, as time goes on, and after a secret conference, seem to realise a futility, and begin to mock The Question. The strife is over for the moment. After they disappear The Question is asked for the last time, and the Silences are heard beyond in Undisturbed Solitude

(The capitals are the composer’s own). Nonsense? Profundity? Mysticism? You decide.

Interestingly (I hope), this analog monaural recording was engineered by Peter Bartok, son of the composer Bela Bartok (above).

The Second Symphony of Charles Ives is clearly indebted to the symphonies of both Brahms and the Bohemian Antonin Dvorak. Their lives overlapped by thirty years, and when Ives was composing this symphony Dvorak lay dying in his native land.

Austria dominated the Kingdom of Bohemia until, in the mid 1850’s, certain concessions made it possible for musicians to settle in Vienna rather than seeking their fortunes elsewhere. The first nationalist to go to folk song and use it as a basis for art music and, in effect, establish Czech music, was Bedrich Smetana, but it was Antonin Dvorak (b. 1841) who popularised it. However, since the mid-1950’s, in both Europe and USA, his stock has fallen somewhat, to the point where much of his orchestral music (save the New World Symphony and perhaps the Cello Concerto) is now rarely heard.

This is a mystery, as it is quite difficult to think of another composer (perhaps Schubert?) possessed of such an inexhaustible melodic gift or the natural ability, God given surely, to express it – again, one thinks of Schubert. Perhaps it is because we wrongly think of him as an artist of the second rank, a rustic born into a working class family and, at one time, apprenticed to a butcher – and, it is true, that much of his music has a strong peasant strain. But is this not a strength? Hans von Bulow clearly suffered from this confusion, remarking that he was “a genius who looked like a tinker” but, in almost the same breath, called him “next to Brahms, the most God-gifted composer of the present day”.

Personally, if I have any doubts (and they are few), and they begin to surface, I immediately play the exquisite second movement Adagio from the Symphony No 8 in G major, a work written in less than four weeks, and often described as ‘sunny’. Yes, it is that, but it seems to me to be so much more – could we say ‘optimistic’? G major was considered a ‘rustic’ key, mainly because many popular songs were set at that pitch, but it does lend a child-like quality to the work, something that Mahler picked up on when composing his delightful fourth symphony a decade later. Music that seems to flow as easily as water from a tap.

To end today, a band unfortunately carrying the moniker ‘supergroup’ around their necks. The Gloaming were formed a couple of years ago by the man at their heart, the violin virtuoso Martin Hayes, and his friend the guitarist Dennis Cahill. Dubliner Caoimhin O Raghallaigh joined them on violin and 5-string viola, plus the Norweigian drone-fiddle, the hardanger. They use no bass, and no drums, but the young pianist Thomas Bartlett, who has worked with a number of well known rock musicians, brings some weighty ballast to the group sound. Floating over this is the ethereal voice of Iarla O Lionaird, a singer in Gaelic from the Cuil Aodha enclave in west Cork. Together, they seem to have put more than a ‘twist’ onto the traditional Irish jigs and reels; here is almost a new form of music that is both ancient, and brand new, and well expressed in Opening Set, from a recent concert in Derry.

“The strings play ppp throughout with no change in tempo. They are to represent The Silences of the Druids who Know, See and Hear Nothing.” reminded me of Spinal Tap’s ‘Stonehenge’ intro –

In ancient times…Hundreds of years before the dawn of history

Lived a strange race of people… the Druids

No one knows who they were or what they were doing

Thanks for the Gloaming vid- sounding very good here in my study with the darkness of the longest night drawing in