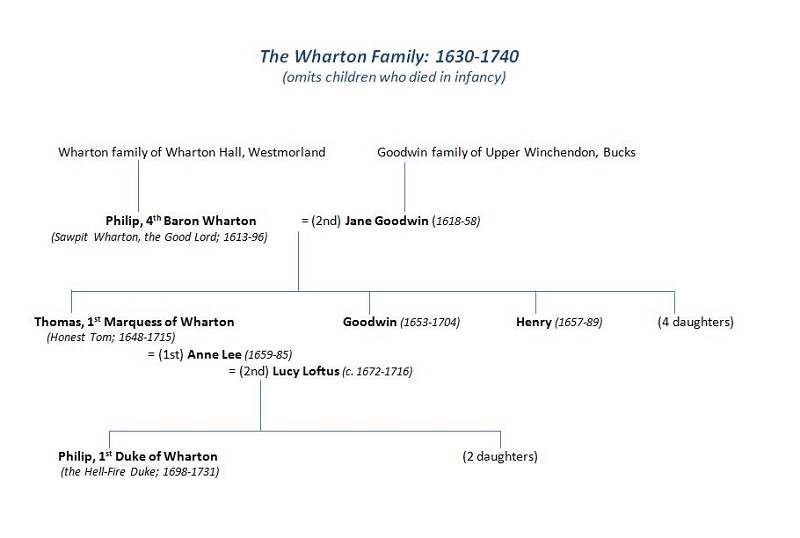

Continuing our weekly serialisation of Jonathan Law’s The Whartons of Winchendon, we meet Philip Wharton, son of Thomas. His pious grandfather had been known as ‘The Good Lord’, but Philip, founder of ‘the Hellfire Club’ (devoted to drinking, lewdness, and puerile acts of blasphemy), was a somewhat different character…

May it please God to shorten

the life of Lord Wharton

And set up his son in his place,

Who’ll drink and who’ll whore

And a hundred things more

With a grave and fanatical face – ….

Although many blamed Philip Wharton for the death of his father, the young man himself showed little sign of guilt or grief: indeed, there is a sense in which he would go on committing parricide in one way or another for the rest of his short hectic life. Given the nature of his antics over the next fifteen years, it is perhaps a mercy that Tom Wharton did not in fact live to see them.

As Philip was still not of age, his guardians arranged for him to spend two years travelling through the Protestant states of Europe with a strict Calvinist tutor. This did not go exactly to plan. After just a few weeks, Philip managed to give his tutor the slip and fled Geneva for the fleshpots of France. Here he began to spend money with abandon – the first stage in a career of profligacy that would not be equalled in the whole of the 18th century. More damagingly still, he made contact with the court of the Jacobite Pretender, James Francis Stuart, and sought an audience. According to his later account, Philip experienced an epiphany the moment he set eyes on James: “I was struck with a becoming awe when I beheld Hereditary Right shining in every feature of his countenance and … the majesty of his person”. Just to be quite clear, this was the son of the Wharton family’s greatest enemy, King James II, and the man Honest Tom had spent half his career trying to thwart; also the man who had inspired an armed rising against the British state only months earlier. Having made his submission, Philip accepted the title ‘Duke of Northumberland’ and a large sum of money – perhaps his real motive all along – but agreed to keep his allegiance secret for the moment; surely he could be most useful in England, as a sort of fifth columnist within the Whig establishment.

With only the briefest stop in London, young Wharton made his way to Dublin, where he entered the Irish House of Lords and quickly made a name for himself as a witty and powerful speaker. Although his speeches were unexceptionably Whiggish, it seems that certain rumours may already have reached Court. Within months George I took the extraordinary step of creating Philip 1st Duke of Wharton – the first dukedom to be conferred on a non-royal minor since the Middle Ages. This unprecedented honour was no doubt partly intended as a tribute to Philip’s father; but it also looks like a desperate attempt to settle the loyalties of this brilliant but rather troubling young man.

In 1719 Philip at last got his hands on his father’s estates, which brought in a desperately needed income of some £14,000 a year (in today’s terms over £1.5 million). The young duke now took up residence at Winchendon with Martha, the wife he had barely spoken to since their marriage; a son was born the following year. However, any hopes that Philip might be embarking on a more settled life were soon to be rudely dashed. Income from the Wharton estates was largely swallowed up in servicing his existing debts and new extravagances multiplied daily. As a result, Philip was obliged to mortgage Winchendon to creditors in 1720. His marriage also broke down after the death of his baby son in the smallpox epidemic of that year. Having satisfied himself that this was all Martha’s fault, Philip told her that he would never see her again – a promise that, for once, he seems to have kept.

Wharton was now spending most of his time in London, where he was busy as founder-president of the Hellfire Club – a somewhat shadowy conclave devoted to drinking, lewdness, and puerile acts of blasphemy. Although not much is really known about the Club, it apparently consisted of some 40 high-born persons of whom – shockingly – 15 were ladies. At their meetings, members would dress up as monks or Biblical characters, drink toasts to the Devil in ‘Hellfire punch’, and dine on such dishes as Holy Ghost Pie, Devil’s Loin, and Breast of Venus. It all sounds pretty silly, but rumours of orgies and devilish rites began to circulate, and Wharton experienced his first exciting whiff of infamy. Following a press outcry, the Club would be closed down by the Lord Chancellor in 1721 for “blasphemy and profaneness”. Wharton would go on to indulge his passion for the clandestine in a string of secret societies – the Freemasons, a mysterious anti-Masonic group known as the Gormogons, and lastly the Schemers, a club dedicated to “gallant schemes for the … advancement of that branch of happiness which the vulgar call Whoring”.

Among Wharton’s associates at this time was one Colonel Charteris – a fraudster, pimp, informer, and all-round pleasant guy known to his cronies as the ‘Rape-Master General’. The Colonel was also a ruthless moneylender and soon had Philip in his clutches. Charteris had made a killing by investing in South Sea stock and it may well have been his friendly advice that led Philip to buy in on a big, big scale. When the Bubble burst in late 1720, he was left staring at losses of some £120,000 (in today’s money, close on £15 million). With complete ruin now hanging over him, Philip launched a wild attack on the Whig grandees who had presided over the whole disaster, accusing them of negligence, corruption, and what we would now call insider dealing. His most famous performance came in the parliamentary debate of February 1721, when he delivered a vicious tirade against the Lord Treasurer, Earl Stanhope – an old friend and ally of his father. Stanhope was so shocked by the young man’s vehemence that he collapsed in the chamber and died the next day, apparently of stroke. This, presumably, is not what Thomas Wharton intended when he coached his son in the arts of political rhetoric. Unabashed, Philip would continue his attacks on the Whigs and the new prime minister Robert Walpole – most notably in his journal The True Briton, which the government repeatedly tried to suppress. The administration would come to regard Philip as its most dangerous and unpredictable foe: a man whose words could quite literally kill.

With powerful enemies and his debts spiralling rapidly out of control, Wharton could only hold off the crash for so long. In 1725, when the sale of his Irish properties failed to satisfy his creditors, Philip was brought before the Court of Chancery and ordered to dispose of his remaining assets. Winchendon – his father’s much-loved Winchendon – went to the Marlborough family, while the priceless collection of Lelys and Van Dykes – Old Philip’s pride and joy – was snapped up by Robert Walpole. (The paintings would later pass to Catherine II of Russia and form the core of the great Hermitage collection.) The entire fortune of the Whartons – one of the greatest in the land – had been dissipated in six or seven years. Perhaps feeling that he had nothing left to lose, Philip now came out as an open and unapologetic Jacobite, attacking not just the government but the Royal Family and the whole Hanoverian settlement. At some point he slipped quietly across the Channel, never to return.

***

Although colourful enough, Wharton’s years in exile make a deeply depressing study. Having offered his services to the Pretender, he was despatched to Vienna with the task of securing Austrian support for a Jacobite invasion of England. For all his love of conspiracy, Philip proved totally unfitted for this kind of work, being naturally indiscreet, constantly drunk, and dogged at every step by English spies. When the Austrians rejected his proposals outright in 1726, he was sent on a similar mission to Madrid, where he attempted to put together a grandiose plan for a joint invasion of Britain by Spanish, French, and Russian forces. The Spanish, however, were no more impressed than the Austrians: in his diary, the Duke of Lyria summed up this strange visitor as a man without “faith, principles, honour, or religion – lies in every word, is cowardly, indiscreet, and a drunkard, possessed of all the vices. His only good quality: being an admirable fawning toady”.

Wharton did, however, make one notable conquest in Madrid; when news came of his wife’s death, he fastened onto one of the Queen’s maids of honour and the two were married within weeks. At the reception, Philip demonstrated his diplomatic skills by getting hopelessly drunk and exposing himself to the grave dons and doñas of the Spanish court (it was time, he declared, that his bride saw “what she was to have that night in her gutts”). An important consequence of the marriage was that Philip now became a Roman Catholic – something that his father and grandfather would surely have found more shocking than the rest of his exploits put together. This in turn meant that he lost much of his usefulness to the Jacobite court – a Catholic duke having far less propaganda value than a Protestant duke of famously Protestant stock. From this time on Philip would be gradually frozen out of Jacobite counsels and his income from these sources began to dry up.

It seems to have been out of sheer poverty that Wharton now accepted a commission in the Spanish army. And it seems to have been out of some deep need to refute the slur of cowardice – a slight that had stuck to the family name since old Sawpit’s conduct at Edgehill – that Philip insisted on leading a charge at the Siege of Gibraltar in 1727. Although the action itself bordered on farce – Philip got blind drunk, ran around shouting obscenities, and suffered a wound to his foot that permanently ended his military career – the repercussions were serious. In bearing arms against the forces of his own country he had crossed a final, fatal line. Back in London, Wharton was charged with high treason and declared an outlaw by resolution of Parliament, thereby forfeiting all his titles and any remaining property.

With the accession of George II in 1728 Philip made one last attempt to find a way back, pathetically offering a deal in which he would trade Jacobite secrets for a pardon. However, he was now so deeply distrusted on all sides that his offer was rejected out of hand. It was perhaps fury at this treatment that led him to publish the most damaging of all his attacks on Walpole and the Hanoverians, an “infamous, scandalous, and treasonous libel” known as the ‘Persian Letter’; publication would lead to some 20 arrests and an all-out assault on the freedom of the English press. Astonishingly, Walpole would now write secretly to Wharton offering to resolve all his debts if he would only agree to leave off writing. Even more astonishingly, Philip – who had been reduced to scavenging for food – refused.

The end would not be very long. In 1730 a shabby, malnourished figure sought refuge at the Royal Abbey of Santa Maria de Poblet, a Cistercian monastery in Catalonia. Here, among the largely silent brethren and the regular bells for prayer, the Hell-fire Duke would once more adopt the habit of a monk. He would die the following year, at the age of 32. So it was that the last of the Whartons found his rest among the medieval kings of Aragon, also entombed at Poblet.

***

Beyond acknowledging that he was a mass of contradictions and really messed up big-time, Wharton’s contemporaries had no idea what to make of his extraordinary career. Nor has the passage of three centuries done anything to resolve the obvious questions. Renegade Whig or loyal Jacobite? Calvinist, atheist, Satanist or Catholic? From our perspective, there is something almost postmodern about this man’s ability to pick-and-mix beliefs. When Alexander Pope considered Wharton in his Moral Essays, he concluded that the only common thread was a craving for praise and attention:

Wharton, the scorn and wonder of our days,

Whose ruling Passion was the Lust of Praise:

Born with whate’er could win it from the Wise,

Women and Fools must like him or he dies;

Though wond’ring Senates hung on all he spoke,

The Club must hail him master of the joke …

His Passion still to covet gen’ral praise,

His Life, to forfeit it a thousand ways;

A constant Bounty which no friend has made;

An angel Tongue, which no man can persuade;

A Fool, with more of Wit than half mankind,

Too quick for Thought, for Action too refin’d;

A Tyrant to the wife his heart approves;

A Rebel to the very king he loves;

He dies, sad outcast of each church and state,

And, harder still! flagitious, yet not great!

Ask you why Wharton broke through ev’ry rule?

‘Twas all for fear the Knaves should call him Fool.

This may be just; Wharton was doubtless a weak and silly man, and in very many respects his life was both sordid and ridiculous. And yet there is something about his downfall – its speed, its terrifying completeness and finality – that has to provoke a kind of awe. Although his life could almost have been scripted to point a moral, any lesson you try to draw from it – live within your means, take more water with it, try not to commit treason – appears embarrassingly inadequate: so trite as to be almost contemptible. Finally, this was tragedy: a man under the lash of the gods.

***

It is almost true to say that nothing now remains of the Whartons, but that would be to forget the Seven Trees.

On Philip’s death all the Wharton titles became extinct except the baronetcy, which passed briefly to his sister Jane before falling into abeyance. The great house at Winchendon sank slowly into disrepair and had to be pulled down in the 1750s; of the famous gardens, no vestige remains except for some humps and lumps in the sheep-browsed turf. The great double avenue that once swept up to the house from over a mile off has, however, been replanted with young trees – as part of a millennium project by the Waddesdon estate, which now owns most of the land. The house at Wooburn – old Wharton’s palace by the Thames – was rebuilt on a much smaller scale in the mid- 18th century and finally bulldozed to make room for modern development. And it is here, in the incongruous setting of a mid-range 1960s housing estate, that the last physical trace of the Whartons can be found. As we know, Tom Wharton resolved to memorialize his father by planting at Wooburn one tree of each kind mentioned in the Bible; of these, seven fine specimens remain. In the little recreation ground, a pair of white poplars that once formed part of an avenue to the church; not far off, a black mulberry tree, a rare cut-leaved walnut, and a beautiful evergreen holm oak. Deeper among the streets and houses, seek out the stately Palace Plane, its 30-foot girth lording it over a small suburban garden. And rising above it all, the fabulous Blue Atlas cedar, floating its green-grey, blue-silver foliage into our ordinary sky.