Barendina Smedley stumbles across a less reported view of a momentous year…

A few days ago, a battered copy of the Studio Year Book turned up here. The date on the much-sellotaped cover was 1939.

To move beyond that cover is to embark upon what feels like an act of low-cost, high-speed, deluxe time travel. Here, set out in elegantly austere spreads, mostly monochrome but punctuated here and there with assertive, rather oddly-faded and hence surreal colour, is much of the best and the worst of the late 1930s, viewed through the equivocal lense of domestic architecture, design and decoration.

On one hand, there is all the usual planning, illustrated ‘schemes’ complete with floorplans and diagrams, functionalism, aspirations towards social engineering, and progress apparently marketed as an end in itself. But then on the other hand, there is style, wit, eclecticism, variety and complexity, a desire to balance comfort with fun, utility continuously undermined by the assertion of individual taste.

Inside the front cover is an advertisement. Under the banner ‘Brighten your Home’ the reader is first tempted by the promise of abundant illustrations, then promised ‘In addition to the illustrations there will be news from the world’s art centres and a comprehensive review of the applied arts and handicrafts and new contributions to gracious living and cultivated taste.’ The price of an annual subscription is ’28s. Inland, 30s. Abroad’.

There is also the appearance of optimism — and not only in those ‘before and after’ sequences, where the architectural données and heirlooms of the past are assimilated into that frail and heartbreaking thing, the thoroughly cutting-edge style concept, either.

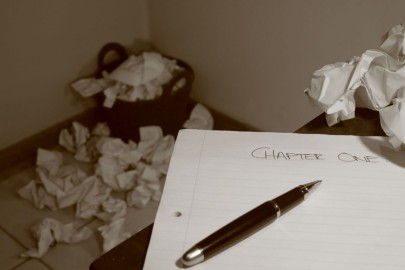

For where the act of time travel breaks down is precisely the point at which the present-day reader tries to reconstruct what those architects, designers, editors, copywriters, photographers, typographers and advertising men could possibly have been thinking. Even allowing for rather long lead-times, did the people who put the Studio Yearbook 1939 together really imagine that this brave new world of modernist bungalows, rational kitchen schemes, unvarnished oak, plate glass and aluminium detail was going to last out the next few months, let alone the next few years?

For the Studio Yearbook 1939 portrays — perhaps ‘invokes’ or ‘aspires towards’ might be a better way to put it — a peaceable kingdom of forward-looking visual and material culture. It isn’t as if national boundaries vanish here. On the contrary, locally-inflected style is feted as gaily as modernist internationalism. ‘Re-orientation in the German House’ does not look exactly like ‘Houses in California’, any more than ‘The Modern House in Italy’ is identical to ‘Modern Houses in Central Europe’ — although it must be said that the overall tone is less one of declamatory speech-making than friendly if somewhat competitive conversation.

No, the oddity here is the apparent thoroughness with which these carefully-concocted modernist spaces have been insulated against wars and rumours of wars. If, two thousand years hence, the Studio Yearbook were all historians had by way of source material for 1939, they would be justified in regarding that year as one of notable stability, material prosperity, international cooperation and geopolitical civility. ‘Gracious living and cultivated taste,’ as that advertisement puts it, really does seem to be the order of the day. Whereas the start of a hugely destructive near-global conflict doesn’t seem likely at all.

And that, I suppose, is the real problem with time travel. Here in 2011, it’s surely impossible to turn the pages of the Studio Yearbook 1939 without wondering what happened to all those immaculate white carpets, plate-glass windows, dining tables elaborately set for leisure and indulgence, imaginative kitchen appliances, eggshell-thin porcelain stamped with whimsical motifs, cocktail counters, vitrious mosaic-murals — or indeed, as far as that goes, without speculating what happened to the men and women who designed, produced or documented them.

How, though, did it seem in 1939? Try though we might, look though we must, in the end we simply cannot quite make our way into those pictured rooms — those carefully-choreographed spaces — perpetually unpeopled, still, silent, balanced with something that might be either utter idiocy or perhaps a certain magnificence on what we, at least, now know to be the edge of the abyss.