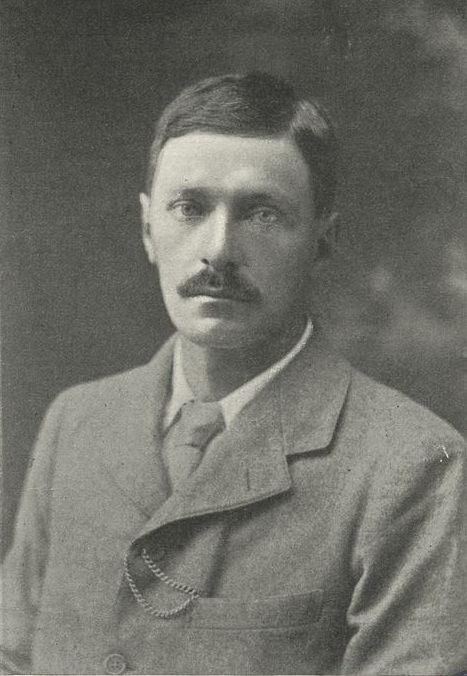

The lead article in the current issue of the excellent Slightly Foxed quarterly magazine is by none other than our own Jonathan Law, who looks at the work of Tarka the Otter author Henry Williamson. You can read the original piece here.

Last week, in the first of two exclusive follow-up articles for The Dabbler, Jonathan explained how Williamson became a committed Nazi, and today he concludes the series by examining his final years, and how he became an unlikely hero for the burgeoning hippy and green movements….

In 1946, at the close of the long war that he had so bitterly opposed, Henry Williamson made a solitary return to North Devon and the landscapes that had inspired him to start writing some 25 years earlier. His marriage had collapsed, he was mentally and physically exhausted, and his reputation was in tatters. And yet at this low point, at the age of 50, he would begin to plan the most ambitious work of his career – a series of 15 full-length novels in which a version of his own family history becomes the basis for a vast panorama of English life in the first half of the 20th century.

A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight would take Williamson over twenty years to complete, with the first volume, The Dark Lantern, appearing to faint praise in 1951 and the last, The Gale of the World, to an awkward silence in 1969. At almost three million words (of which I have read perhaps two thirds) this is without much doubt the longest novel sequence in English – probably more than twice the length of Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time. It needs to be said at once that the books have most faults that a novel can have: they are longwinded, ineptly plotted, and lack both focus and narrative drive; the attempts at social comedy are mostly laughable and the dialogue (literally) unspeakable. But all this said, they have the important merit of being very readable; indeed, once you have chewed your way through two or three of them, they become alarmingly addictive.

Why this should be, I don’t know. It’s a dodgy argument, but I can only suggest that in some odd way the lack of shape and polish works to enhance the feeling of real lives being lived that these books really convey (shape and polish being high on the list of things our lived lives lack). The design of the novels is about as far from the Jamesian ideal as could be; events with no real significance in the wider scheme of the book are treated at length, simply because something of the kind once happened to the author. Despite its obvious drawbacks, this can pay off – most spectacularly in the five books based on Williamson’s experiences in World War I. Here the Chronicle achieves genuine, if intermittent, greatness. The loose structure gives free rein to Williamson’s savant-like powers of recall and description and helps to create an uncanny impression of truth to life: very simply, the books provide a stronger sense of what it must have been like to live through the trenches – the sounds, sights, and smells – than any others I’ve read. This makes them gruelling reading. But some enterprising publisher really ought to get these novels in print again (even if somewhat abridged).

Blessedly, the earlier books in the series show few signs of their author’s ugly politics: indeed, with their generalized social concern and rather obvious attacks on establishment figures (war-mongering journalists, un-Christian clerics) you would probably put their author vaguely on the left. The huge supporting cast includes a few Jewish characters and these are treated with no lack of respect. However, all this changes abruptly when we come to the last four volumes, those dealing with the events of the 1930s and 40s; here it becomes painfully clear that Williamson has not altered his views in the slightest. The novels are overtly fascist – the only English novels I know of which this can be said. In The Phoenix Generation Williamson presents the national socialism of Hitler and Mosley (‘Hereward Birkin’) as a heroic rising from the ashes of war and Depression. A Solitary War – which Williamson dedicated to the Mosleys – gives unstinting praise to the Hitler who (we are told):

freed the farmers from the mortgages which drained the land, cleared the slums, inspired work for all the seven million unemployed, got them to believe in their greatness … the former pallid leer of hopeless slum youth transformed into the sun-tan, the clear eye, the broad and easy rhythm of the poised young human being.

And Lucifer before Sunrise takes a final step into madness, with the dead Hitler lauded as a “chaste Saint, above earthly impulses” and a “flawed Christ … killed by the lack of imagination of others”.

However inured to the political idiocy of writers you might consider yourself to be, it’s pretty shocking to read this stuff in a novel of the late 1960s. As with those who stayed loyal to the Party after Stalin, after Hungary, after everything anyone needed to know was known, the sin is all in the persistence – the refusal even to think about thinking again. At some point folly this stubborn tips over into something it’s hardly worth trying to distinguish from wickedness. God alone knows what Williamson’s publishers must have felt. Although Macdonald continued to issue the Chronicle, the books were no longer reviewed or promoted – and hardly seem to have been edited. Apart from their other failings, these late novels seem very hastily written: the author who had revised parts of Tarka thirty times now seemed content to publish first-draft material. As he entered his seventies, Williamson must have known that his great project was running out of time.

***

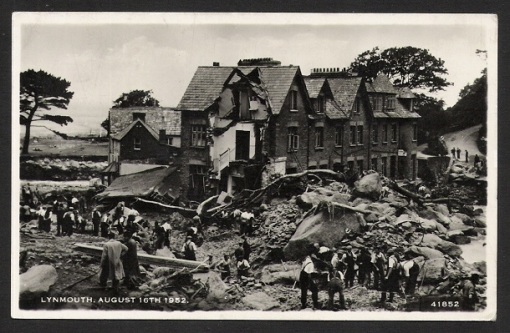

Fittingly, the very best and worst of Williamson come together in the last Ancient Sunlight novel, The Gale of the World (1969). This is a book that I could not in good conscience recommend to anyone – yes folks, a mostly boring, badly written book that sucks up to Hitler’s ghost and even takes in some half-hearted Holocaust revisionism! A sure thing for Richard and Judy, no? Yet if you have the good taste to ignore this novel you will miss something unforgettable. In the last fifty pages Williamson brings his life’s work to an end with a bang – an absolutely hair-raising account of the freak storm and flood that blasted Lynmouth in August 1952. This is quite simply one of the great set pieces of descriptive writing produced in the last century.

As the rain sheets down onto the already waterlogged bogs of Exmoorand begins to roar into the narrow gorge of the Lyn, all sorts of other stuff is happening and all of it is mental. Outraged at the injustice of the Nurembergtrials, members of the village cricket team are flying through the storm in gliders to rescue Rudolf Hess from Spandauprison (happens all the time, I know). Meanwhile, a half-crazed Phillip Maddison, the H. Williamson character in the books, is up on the Chains, the wildest part of Exmoor, building a pyre for his father’s corpse: he contemplates suicide but is saved from this fate when he is struck by lightning. As the great storm – the Gale of the World – breaks on Phillip’s head, the wild imagery takes us back to the trenches but also sums up the tumult of a life:

These lower, darker cumulus clouds were fuming and tumbling … Forked lightning hissed continuously; air-cleaving bolts released a smell of sulphurous oxide out of rainpools instantaneously seeming to be made to boil and cool again in one stroke. Down flailed blobs of ice, to bounce on back and head of Phillip … After the barrage of hail came the bayonets of rain, stabbing thick and hard; but it was warm after the hail. And soon The Chains, fifteen hundred feet above the sea, was a glittering sheet of water from which a semblance of glassy thistles rose a foot high and side by side, so violent was the down-hurled rain. And the tops of the clumps of sedge-grass were linked by pale blue waving gossamers of St. Elmo’s Fire. Hurray! Hurray! …

How ironic, that I was nearly destroyed by the defects of what qualities I possess! No funeral pyre in this slashing, roaring, lightcracking battlefield night the very elements at war … the old gods come together to thwart my cowardice, to bestow on me their gifts of courage!

Those curious rosy lights playing about below the senior flashes of the sky-cracking purple jags: fire-balls in play, shooting up from moor grass clumps and the wilted white tufts of the cotton grass, to die away and be succeeded by others, each pink ball about two feet in diameter, and all gentle, a rosy play of infants while the giants fling their bolts in great angry veins of electric death!

I can go home after all this, I have a warm place to go to, I am free, this isn’t Passchendaele there all were homeless – I am free …

A cloud directly above him was changing colour from a dirty grey-green to a ghastly swirling white as it heaved like a conglomeration of enormous maggots. It had such a sinister appearance that he stood still upon the tumulus and stared up at it, a discoloured Chinese dragon … then from one tentacle lowering upon the earth issued a stunning flash. He felt a blow on the top of his head, breaking body from legs as the earth rose up to his eyes.

In these pages – and it really does go on and on like this – the Götterdämmerung strain that had always been present in Williamson finds its most extraordinary expression. After the years of bitterness, it’s like a great boil bursting in his psyche. Magnificent, of course – but observe the narcissism that takes a natural disaster on this scale and turns it into a personal catharsis for himself and his hero.

***

Who read The Gale of the World in 1969, and what the hell can they have made of it? The question is fascinating, not least because Williamson had begun to find an audience again. Suddenly the old fascist had admirers in the burgeoning hippy and green movements. His long-term anti-Americanism, anti-capitalism, and environmentalism were now quite the rage, as were his interests in Eastern religions, Jungian archetypes, yes all that. It seems the hippies saw Williamson rather as the Beats had regarded Ezra Pound in the 1950s: the guy may be a fascist, but at least he isn’t a square.

Indeed, if you look back at the hippyish sentiments in Williamson’s earliest novels, written in the wake of World War I, there’s a curious sense of things having come full circle. While Henry marched against the Vietnam War, his son Harry became a minor figure on the alternative music scene, taking up with various members of Gong and Hawkwind. New offers began to come in: plans were made to film Tarka and Williamson even went on Desert Island Discs (luxury item: a cor anglais). In 1969 BBC TV broadcast a respectful interview from his farm, in which he holds forth on the evils of pollution and city life. He comes across as a sweet old boy: but they had to tweak the footage, to hide the giant swastika he’d painted on his barn.

With a weird synchronicity that Williamson might have liked, he died on a summer’s day in 1977 – just as a crew was shooting the death of Tarka, under the teeth of the hounds, at the wide mouth of the twisting Torridge River.

This is quite simply one of the great set pieces of descriptive writing produced in the last century

Your two posts on this subject rank pretty high on the list for this century. Thank you.

Fascinating series, Mr Law. Thanks.

In 1969 BBC TV broadcast a respectful interview from his farm, in which he holds forth on the evils of pollution and city life. He comes across as a sweet old boy: but they had to tweak the footage, to hide the giant swastika he’d painted on his barn.

Around the same time David Irving was a celebrated historian despite his less than carefully veiled sympathy for the Nazis, and Oswald Mosley made regular appearances on television. For all the complaints when Eric Hobsbawm died that he would never have been praised had he supported Nazism it clearly wasn’t long ago that fascism would have been no obstacle to public regard.

I have really enjoyed reading this series Jonathan, and how apt to be left with Williamson casting himself as a sort of Lear figure upon the blasted heath, railing against the society that has spurned him

Also mightily impressed that you’ve managed to read that much of his stuff

Yes, I had no idea that Williamson was responsible for the longest novel sequence in English.

A brilliant trilogy, JL.

Fascinating.

I can’t quite put my finger on why, but this sentence:

As with those who stayed loyal to the Party after Stalin, after Hungary, after everything anyone needed to know was known, the sin is all in the persistence – the refusal even to think about thinking again.

is perfect.

Not mostly for what is says, but the way it says what it says.

I can’t recall reading a piece of literary criticism and biography as enjoyable (if disconcerting) as this. Full of memorable phrases and striking observations. I wish it were a book.