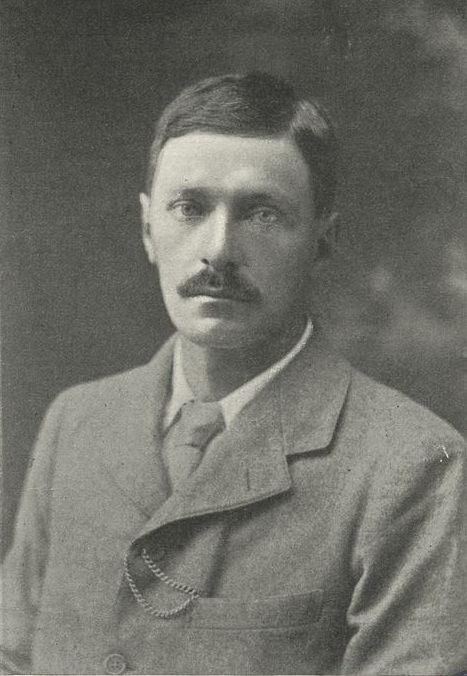

The lead article in the current issue of the excellent Slightly Foxed quarterly magazine is by none other than our own Jonathan Law, who looks at the work of Tarka the Otter author Henry Williamson. You can read the original piece here. In the first of two exclusive follow-up articles for The Dabbler, Jonathan explains how Williamson became Adolf Hitler’s most besotted English admirer…

In 1930 Henry Williamson had every reason to feel pleased with life. The success of Tarka the Otter – published three years earlier to stellar reviews and already in its third printing – meant that he was famous, admired, and on the way to becoming wealthy. A man once regularly mistaken for a tramp now wore good tweeds, hobnobbed with the likes of John Galsworthy, and had a membership at the local yacht club. He bought an expensive sports car, an Alvis Silver Eagle, and drove it very fast. But just ten years later Williamson would be a lonely, vilified figure, shunned by his neighbours, despaired of by his friends, and largely forgotten by the literary world: many people thought he should be in prison. What happened?

In a word, Hitler happened – and the author of much-loved animal tales became perhaps the Führer’s most besotted English admirer.

In a way, that Alvis was to blame. In the summer of 1935 Williamson was feeling jaded and written out, bored with otters and salmon and North Devonand very conscious of having turned 40. We might charitably describe it as a mid-life crisis. At this moment he receives a letter from an old friend, inviting him on an expenses-paid motoring holiday in Germany: they can drive their flash new cars on the flash new autobahns! The German Writers’ Guild will be most helpful, and the jaunt can end with a visit to that year’s Nuremberg Rally.

Williamson obviously enjoyed himself immensely and described his adventures in Goodbye, West Country (1937), a light-hearted memoir that no one has seen fit to reprint. Like other observers of the time, he is impressed by Hitler’s public works, the creation of mass employment and all the rest of it. Like some other veterans of the trenches, he is all for Anglo-German reconciliation. But Williamson’s observations have a jaw-dropping quality all of their own. He is, for example, moved by Hitler’s humanitarianism – hasn’t he banned the police from using rubber truncheons? And don’t believe that scare stuff in the papers about repression and violence: “everywhere I saw faces that looked to be breathing extra oxygen; people free from mental fear.” The Hitler Youth bring back fond memories of time as a Boy Scout, while in the Brown Shirts he sees “the spirit of English gentlemen” – but gentlemen who have “transcended class-consciousness”. When the trip reaches its climax at Nuremberg, Williamson is overcome by the spectacle, finds himself shouting “Heil Hitler! God Save the King!’

There is one further exquisitely sinister moment: back at his hotel, Williamson, drunk on champagne, takes a photograph of himself shaving in the mirror. His hair has become parted, the shaving foam has cut off either end of his moustache. A familiar apparition glowers back at the author of Tarka the Otter.

***

Back in England, Williamson lost no time in announcing his new allegiance. When his early tetralogy of novels, The Flax of Dream, was reissued it came with a preface in which the author declares, “I salute the great man across the Rhine, whose life symbol is the happy child.” In another new passage, the hero gushes:

There is an ex-corporal with the truest eyes I have ever seen in any man, now rousing the young men and the ex-soldiers, to save the nation from disintegration: a man who doesn’t smoke or drink, a vegetarian owning no property, living for the sun to shine on the living.

Those who already knew the novels might have found this pretty odd; on the face of it, the books preach a message of benign nature worship, interspersed with lively rants about the evils of war, nationalism, and industrial civilisation. You could describe the philosophy as a mixture of Rousseau, Shelley, and St Francis, with perhaps a dash of Lenin and a dollop of Fotherington-Thomas. Reading the books now, we might easily see them as the work of a proto-hippy, not a budding fascist.

The question that most fascinates – and troubles – is how far Williamson’s fascism was a mad aberration, and how far it reflected toxins already latent in his thought. A “religion of nature” can seem an attractive, life-affirming thing, but in practice it tends to go a bit like this: worship of nature shades into worship of vitality, which shades into worship of power, which shades into worship of cruelty. As we have seen, the vitalist creed preached by Williamson certainly involved an imaginative engagement with cruelty – the emphasis on hunting and killing has struck some readers as sadomasochistic. The world of Tarka the Otter is one of pristine energies, unsullied by doubt or reflection; there is a fierce kind of purity here that sits uneasily with the benign muddle of a democracy.

Quite apart from its ferocity, there are clear points of contact between Williamson’s cult of nature and the emphasis on the natural, the organic and holistic that formed one strand of Nazi ideology. He would not be the only sensitive type to be sucked in by this style of talk. In a passage of haunting pathos in his Autobiography, Edwin Muir writes of the time he spent at Hellarau, a back-to-nature settlement near Dresden that attracted cranks and idealists of all stripes. As described by Muir, this was a setting where the young Williamson would have felt much at home:

The worship of nature was a powerful cult in Germanyin these years after the war … in the weekends the simple-lifers, the direct worshippers of nature, came out from Dresdenand crowded in the woods. They called themselves the Wandervogel; they neither smoked nor drank; instead they carried guitars, and sang German songs, and kindled ritual fires, and slept, young men and women together, in the woods. The war had wakened in them a need to be with harmless unwarlike things like trees and streams, and to move freely through peaceful spaces. Most of them, I have been told, were carried away later by the gospel of Hitler. They had nothing but simplicity and a belief that smoking and drinking were evil to protect them against him.

Williamson’s great, tragicomic delusion was to see Hitler in his own image, as a prophet of anti-industrialism and ecological renewal. Apart from its sheer folly, this suggests a narcissism more serious than anything involving shaving foam and a mirror. Indeed, reading his later apologetics you might get the notion that Hitler was above all an agrarian reformer who regrettably allowed himself to be distracted by other matters (a World War, a spot of genocide). Say what you like about Adolf, he had some good ideas about forestry, cared about the wildlife. At times Williamson’s take on Nazi Germany is pure Springwatch for Hitler.

Even more oddly, Williamson convinced himself that Hitler shared his own quasi-pacifist beliefs – the Führer, we are told, is “the only true pacifist in Europe”. Here Williamson was led astray by his life-shattering experiences in the trenches – and most critically by his participation in the famous Christmas truce of 1914. As he states time after time, this left him with a simple conviction that Englishmen and Germans were “brothers” and must never fight again. His weird tendency to identify with Hitler was compounded when he learnt that young Adolf had been serving on just that area of the front at Christmas 1914: surely Hitler had to feel the same way about these things? Possibly, just possibly, the two of them had met!

Three weeks after my eighteenth birthday, I was talking to Germans with beards and khaki-covered pickelhauben, and smoking new china gift-pipes glazed with the Crown Prince’s portrait in colour, in a turnip field amidst dead cows, and English and German corpses frozen stiff. The new world, for me, was germinated from that fraternization. Adolf Hitler was one of those ‘opposite numbers’ in long field-grey coats.

In reality, Hitler was in the reserve trenches, a mile or two back. News of the incident left him pale and shaking with fury. There’s an instructive passage in The Flax of Dream where the young idealist Willie Maddison, a clear surrogate for the author, is reproached by a friend for going on about Lenin’s philosophy when he has never read a word of it. “I know Lenin intuitively,” Willie replies. I don’t think this is meant to be funny. The trouble is that Williamson thought he knew Hitler intuitively. It’s part and parcel of his romantic anti-intellectualism. Elsewhere in the book Willie extols the “unspoilt, unthinking mind” of the child uncorrupted by formal education. Williamson’s mind, you have to conclude, was in some ways very unspoilt indeed.

Whatever mental process brought him to these views, Williamson would now stick to them through thick and thin. He became a dedicated member of the British Union of Fascists, lauded Oswald Mosley as the greatest Englishman of the age, and wrote articles for the party newspaper, Action, until it was banned in 1940. Even after the declaration of war, you can find him proclaiming that Hitler is “determined to do and create what is right. He is fighting evil. He is fighting for the future.” Detained very briefly in 1940, Williamson was released on the understanding that he might prefer to keep such thoughts to himself. For the rest of the war he struggled to farm a thankless piece of Norfolk on strictly organic principles, apparently seeing this as some sort of microcosm of Hitler’s and Mosley’s struggles to regenerate their nations. His literary career was more or less deep-frozen, although he kept up a stream of articles inveighing against nitrate fertilizers and white bread, which he seemed to see as the root cause of the war. The death of Hitler hit him very hard.

The story might fittingly end there; but it is some sort of tribute to Williamson’s cussedness that his greatest literary endeavour was still to come.

Really interesting post, Mr Law.

…a man who doesn’t smoke or drink, a vegetarian owning no property, living for the sun to shine on the living.

This isn’t an original insight – I can’t remember who I gleaned it from – but there’s a temptation to admire politicians who seem to transcend the petty selfishness and artifice so rife in politics. Sometimes, though, the purity of these mens’ visions is a consequence of their ideological fanaticism and we’d have been better off with a corrupt, self-serving but essentially unambitious sod.

The obsession with bread seems to have been commonplace…

Ah, yes; those baguette-eating surrender monkeys.

As for Germany’s wartime bread:

‘Bread, as an essential staple of the German diet, was adulterated with just about anything […] and loaves began to get increasingly grey, even green, in colour, as more additives and alternative ingedients were added. Some claimed that sawdust was being added, while others suspected darkly that bonemeal was now included […] With a gritty texture and a taste reminiscent of cardboard, wartime bread was barely palatable.’

Roger Moorhouse Berlin at War (2010)

Splendid stuff Mr Law. I remember being struck by the savagery of Tarka The Otter when I was presented with it as a set book at the age of 12 or 13. This and you previous Williamson post have been fascinating.

As for ‘Springwatch for Hitler’ ? A little gem!

There is an irony here, Williamson, an author who it would seem, made nothing from his writing has as his Idol, Adolf Hitler who as an author, made what may be the largest earner ever from a single book. Did Williamson ever contemplate that I wonder, the advantage of a captive market. Indeed did he ever read Mein Kampf, a book so excruciatingly boring many never get past page twenty. The book, even today, can be seen by the inquisitive eye in a surprising number of Rhein-Pfalz drawing rooms, À la recherche du temps perdu perhaps.

Unity at least had the good sense to apply barrel to temple although it must be said, not with any great accuracy, a not unknown problem with Northumbrians. ‘Tis a pity perhaps that yours truly didn’t share her enthusiasm.

another corker of a post JL, very interesting indeed.

There’s been numerous discussions on here about the fine line between marxism and fascism, and the way that environmentalists often seem close to tipping into either camp with their hatred of other humans clogging up their ‘perfect’ planet

Excellent post. As the last of those who lived through that period pass on, our understanding of the thirties and the war is moving from history to myth in the true sense of the word. The left-liberal narrative that has predominated for decades has left us with the impression that supporters of Hitler and Mussolini were few and were for the most part angry aristocratic misanthropes or unhinged romantics or even semi-psychotic, while the millions who supported the far left were righteous naifs who emoted for the poor and dreamed of a better world. Not very accurate at all. Mosley was motivated by a disgust with urban poverty, not ancient pagan gods, and Hitler had many more admirers than we like to believe.

Worm is quite right about the link between totalitarianism and radical environmentalism. It’s no surpise Williamson retreated to organic farming. Perhaps this is a good argument for changing the royal succession as soon as possible. I think we saw a similar syndrome at work in the posts about Ruskin’s irrigation works on his estate dug in the cause of protesting the horrors of capitalism.

Not sure the link is with totalitarianism, per se. Fascism is motivated inter alia by nostalgia for the organic nation… so there’s really quite a short step between it and radical environmentalism.

I think the left is now deep in it too. The humanism of the old left with its belief in progress has been overtaken by a lot of anti-humanist thinking–neo-Malthusians, climate change alarmists, animal rights radicals, the local produce brigade, anti-globalisation and resource extraction types–all would see better days ahead if half the world’s population disappeared. When combined with the left’s traditional attraction to social engineering and scientism, there’s plenty to furrow one’s brow over.

I agree with that but I’m not sure it makes sense to use left-right categories when dealing with extremists.

It seems to me that on the one hand there are those who believe that liberal democracy is the least worst option, and then on the other those who think there are absolutely ideal ways to organise things if only people could be got out of the way.

Can Lenin and Basil Fotherington-Thomas have ever before shared the same sentence?

Fascinating stuff. There’s nowt so queer as folk.

There is so much more to Henry Williamson than this fixation on his politics which tend to be exaggerated out of all proportion to the reality. HW was not a Nazi, nor a Nazi-sympathiser – terms which carry horrific post-WWII knowledge. To state he was twists the truth. HW was a loyal patriot of this country throughout his life and fought throughout the First World War, an experience from which he never recovered. From that time one of his main life’s compulsions was to do everything in his power to avert further similar carnage. That was his driving force and what lay behind his rather naive and muddled dabbling first in the politics of the left and finding that was not the answer in the 1930s of the right (post-WWII he voted Liberal !!!!!!). HW never condoned the atrocities of WWII (a diary entry of October 1940 refers to Hitler as “bloody wicked”) and always referred to Hitler as ‘Lucifer’ – the chief angel and Bringer of Light fallen to Satanic Evil – a powerful metaphor that has to be taken account of to understand HW’s work.

This whole subject is very complex but I would ask readers to strive for a more balanced view of this difficult, complex, troubled, man, author of over 50 books many of which relate a socio-historical view of life as it actually was in the first half of the twentieth century – not a synthetic hindsight. HW was there and lived through traumatic events: he related it as it was for him with absolute honesty: that is rare.

Visit the Henry Williamson society website (www.henrywilliamson.co.uk) – even read my two biographical volumes!

By the way I personally feel that Tarka can (and possibly should) be seen as an allegory of the First World War: nature is indeed red in tooth and claw, and man is but an aspect of nature.

Anne Williamson, Manager the Henry Williamson Literary Estate.