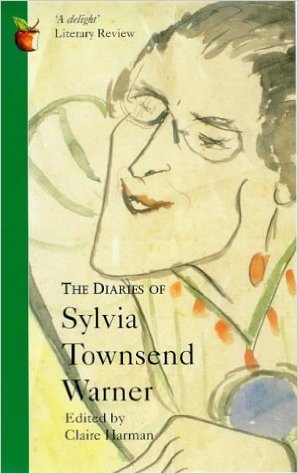

The lead article in the current issue of Slightly Foxed literary magazine is by our own Jonathan Law, who writes about the remarkable diaries of Sylvia Townsend Warner.

Continuing from yesterday, here is the concluding part of an expanded version of the piece, in which Sylvia meets the love (and bane) of her life, Valentine Ackland…

With hindsight, some lives seem to have a single turning point, a moment after which nothing can be quite the same. For the writer Sylvia Townsend Warner such a moment arrived indubitably in the autumn of 1930, when a train of events turned her life alarmingly if delightfully upside-down. Among the many things to change would be the diary that she had kept for the past three years. As her life acquired a new and all-compelling focus, the journal – hitherto a loose medley of wit, brilliance, and charm – would undergo an equivalent transformation. Suddenly, there is a real story to be told – and, by God, it is one of the great love stories of the century.

***

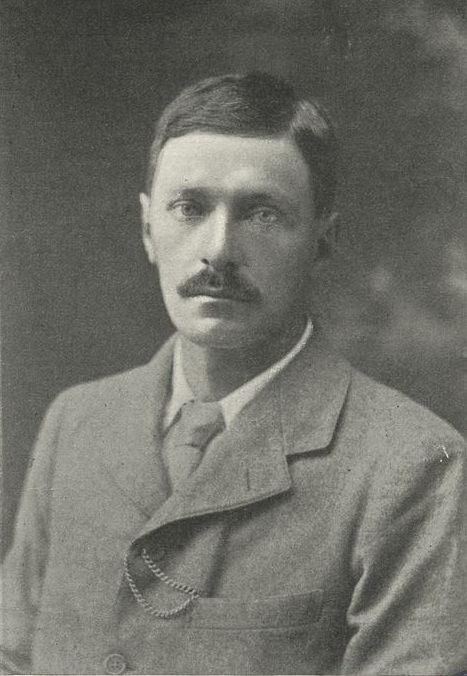

For most of the 1920s Sylvia had been making visits to Chaldon, a remote Dorset village notable as the lair of T. F. Powys, a writer whose grim rustic fables enjoyed a vogue at the time. Although a self-styled recluse, Powys had a gift for attracting devotees (one hailed him as “a blend of Socrates, William Blake and God the Father”) and Warner was among those to succumb to his bloodcurdling charm. With his eccentricity and gloom Powys cut a Johnsonian figure, and for a while Sylvia became a sort of Boswell, filling pages of her journal with his weird obiter dicta. When the opportunity arose to buy a tiny cottage nearby, Sylvia jumped – and through a series of accidents also acquired a lodger: an extraordinary young person named Valentine Ackland.

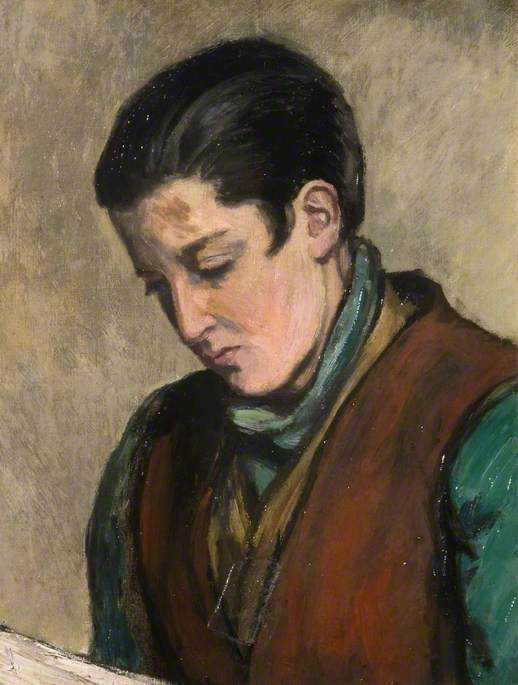

If Sylvia hardly knew what to make of her new housemate, she was in good company. With her cropped hair, masculine dress, and unaccountable behaviour Valentine had spent most of her short life confusing people. The roots of this went back to a deeply unhappy childhood, in which her father, denied a son, had done his best to raise Valentine as a boy. A Catholic education had probably not helped and nor had marriage (later annulled) to a very gay man. Valentine, you could fairly say, had issues.

The diary gives a slow-burning account of the day on which it all changed: October 11, 1930. For some months the village had been disturbed by goings-on at the vicarage, where the tenant, a Mrs Stevenson, was training “mentally deficient” girls to work as domestics. According to rumour, the girls were mistreated and half starved; there had been frequent, pathetic escape attempts and loud sobbing heard from the bedrooms. While others gossiped, Valentine determined to act. With Sylvia in tow and a gun in her pocket, Ackland set off through the “strange stilled light” of the afternoon to confront the terrifying Stevenson. Although nothing was resolved, Sylvia was thrilled by Valentine’s impetuosity and aristocratic fearlessness: “Righteous indignation is a beautiful thing … I watched it flame in her with severe geometrical flames.” That night they would share a bed, the start of passionate relationship that would last for forty years.

Writing in her journal the next morning, Sylvia would hail the new day as “our first … a bridal of earth and sky”; and this heady sense of a world transfigured by love barely diminishes over the weeks and months. Everyday pleasures and activities are filled with a shining, singing joy:

It was amazing happiness to be writing … full of cold snipe and beer, with my love lying beside me, her lappet of hair trailing into the winter grass …

It was our most completed night, and after our love I slept unstirring in her arms, still covered with her love, till we woke and ate whatever meal it is lovers eat at five in the morning …

For Sylvia, her new lover was a thrilling blend of the otherworldly (“as elegant and aloof as a unicorn”) with the robustly down-to-earth; if she sometimes resembled “a solitary sea nymph”, it was a one who could “split logs with an axe and manage a most capricious petrol pump, and cut up large frozen fish with a cleaver”. Above all, perhaps, Valentine made her feel that she herself had risked too little: “All my life I have been dutiful, probably too dutiful, dangerously dutiful anyhow”.

After one particularly joyous night, the couple exchanged vows and from this time Sylvia regarded their relationship as a marriage: “For my part … I loved, I increasingly honoured, and if being bewitched into compliance is obedience, I obeyed; as for fidelity, it seemed as natural as the circulation of my blood …” In 1933 they moved to Frankfort Manor, a mouldering 17th-century grange in Norfolk where Sylvia wrote poems and stories while Valentine shot rats with a rifle. Their happiness appeared to be complete.

It was here, however, in the “kind paradise” of Frankfort, that the cracks began to show. As Sylvia resumed her literary career, Valentine became increasingly bitter at her own failure to get published and Sylvia’s sometimes clumsy attempts to help (they would issue a joint volume of poetry in 1934). Although Ackland is often dismissed as an awful writer, her position was if anything more painful: she had the misfortune to possess a genuine but slight and quite unmarketable talent, and to be sharing a house with a genius. To make matters worse, Valentine had become a very heavy drinker, although the problem was never acknowledged by either of them (occasional physical collapses being put down to ‘migraine’). Sylvia would likewise turn a loving blind eye to her friend’s affairs with other women – a policy that she would come to see as damaging (“the worst injury one can do to the person who loves one is to cover oneself from head to foot in a shining impermeable condom of irreproachable behaviour”). And almost symbolically, the Chaldon vicarage affair that had first drawn them together now came back to bite: Mrs Stephenson sued for libel, and legal costs meant they had to abandon Frankfort for another tiny, freezing cottage.

Very little of this makes its way into the diaries. From the mid-1930s there are long gaps in the record and a strong sense of things not being said. We have to go elsewhere to learn about the big change in Sylvia’s life at this time – her decision to follow Valentine into the Communist Party in 1935 – or about the move to Frome Vauchurch, the riverside house in Dorset that would be home for the rest of their lives. The war years are thinly covered and it comes as little surprise when the diary breaks off altogether in 1945.

When the entries resume, in May 1949, it is in a shockingly different key. The mood is one of black anguish as Sylvia faces the great crisis of her life. For some years Valentine had been pursuing an on-off affair with a young American woman, and she was now determined to move her lover into the house, while retaining Sylvia as a companion. Knowing that she could never accept this, Sylvia saw no choice but to leave, even though the idea of separation from Valentine threatened her very sense of self: “what I cannot begin to imagine is myself alone. The moment I think of that I go out like a candle … There is no one in the room”. As Sylvia wrestles with such thoughts, this sanest of writers seems to hover on the brink of a terrifying mental collapse. There is, she concludes, a dangerous place where “one’s thoughts look towards madness as towards a sheltered valley – still far off & hard to obtain, but … with a wearied longing”. These entries are truly harrowing: but sadder still, perhaps, are those that register the simple pain of knowing oneself unloved:

I kissed the hollow of her elbow – gentle now under my lips, and no stir beneath the skin. She looks as beautiful now as when she was beautiful with love for me …

To feel myself delighting her … that is something I think I shall never feel again; and of all the things I grieve for, it is that I grieve for most.

That September Sylvia moved to Yeovil for a month’s trial separation. While Valentine brought her lover to Frome Vauchurch, Sylvia walked alone on Sedgemoor feeling “idiotic with grief, with care, with bewilderment, with exhaustion of spirit” and (the old genius for simile reasserting itself) “as derelict as an old bus-ticket”. Although she was home within weeks, the situation hung in the balance until the spring, when Valentine quietly admitted defeat. Somewhat to her own astonishment, Sylvia had won:

Here I am, grey as badger, wrinkled as a walnut, and never a beauty at my best; but here I sit, and yonder sits the other one, who had all the cards in her hand – except one. That I was better at loving, and being loved.

The diary reverts to its wonted descriptions of lamb’s tails wagging in the hedges, pussy willows that glisten “like suspended hail”, and Dorset turning pistachio green in the last rays of the sun: but for Sylvia the trauma could not be erased. As she noted to herself: “because one goes on living, one does not realise the extremity which one has lived through. My hair is burned as black as Dante’s with hellfire, and I wonder why it will not lie down in a graceful wave.” Over 12 years later a sudden memory of the separation is “almost an abolition. I waited to hear myself fall in half, as a cleft log does.”

By this time, Valentine had found other ways of giving pain. In February 1956 Sylvia stepped into her friend’s room for a book and saw something that struck her like a blow: “a small rosary by her bed, curled up and neat as a snake”. Valentine had rediscovered the Catholic faith of her youth and would soon, to Sylvia’s horror, begin attending Mass. Unlike twenty years before, when they had both embraced the Party, Sylvia refused absolutely to follow her on this latest journey, and remained deeply hostile. Indeed, Valentine’s observance seemed to cause her a quite intimate disgust (“the physical repulsion I feel at the thought that she sticks out her tongue & has a wafer planted on it”). Although anti-religious feeling was common enough among leftish types at the time, there is something peculiarly vehement about Sylvia’s attitude, which seems coloured by an old-fashioned anti-Catholicism as well as a deal of snobbery. As both women were only too aware, the issue had opened a real and lasting breach (“I … tremble at this enormous & growing distance between us”). In some strange way, the matter became a rerun of 1949: Valentine noted how Sylvia “looked frighteningly like she had looked about Elizabeth – shaken and on the edge of sudden tears”, while Warner wrote to a friend comparing “this Roman Catholic business” to “a third person in the house”.

Although Valentine’s faith remained a lasting source of unhappiness, the diary records “mercies and mitigations” aplenty as seasons pass and the 1950s become the 1960s. In September there is a “a little rusty meadow, with a mere” where they pick blackberries and mushrooms; in January “a sharp blue sky, and the boughs and branches so motionless that each leaf carried its coping of snow as tidily as an eggcup holds its egg”. In the old house by the river there is always something to see and to transcribe: swans with their “narrow severe faces”; an otter screaming “like a woman in orgasm”; a dead heron “extraordinarily flat in its rigid pattern: like a squashed iris”. The similes have the old virtuosic touch: a rescued bat is “as pretty as Mozart”, a massive tabby has “black velvet breeches like Parson Woodforde”, and here are the first snowdrops “holding their noses straight up in the air, & looking like cherubim badgers”. One autumn evening there is Beethoven on the wireless and Sylvia, soon to turn 65, dances among the cats and their saucers and wonders whether “perhaps it was the last time I should dance for joy”.

The great anxiety now was the state of Valentine’s health. For years she had suffered from a pain that was thought to be mastitis, and there were other mystery complaints. In 1968 the word ‘cancer’ is first heard; a lump “the size of a golf ball” is removed from her breast and later there is a full mastectomy. The diary becomes almost unbearably moving as step by step Sylvia is forced to contemplate the unthinkable: “A life without her seems inconceivable: physically inconceivable, like trying to conceive walking without a sense of direction …” By the following summer Valentine is in constant pain and too tired to eat. They travel to London for a crucial consultation and Sylvia feels all the old intoxication as Valentine stoops to give a coin to a match-seller: “All her life was in the gesture. And am I to lose this?” For a moment she is “back in our glorious glorified beginnings”. It is only when they return to Dorset that the truth sinks in; that nothing is being done, that the doctors have decided Valentine is beyond cure: “And she raged. And I could do nothing.”

In October the swans fly overhead and Valentine weeps silently: “This world so lovely, and she with such quick eyes for its loveliness …” The reader, too, may be weeping buckets – and for somebody he or she has probably come to dislike. Valentine dies at home in the early morning of November 9: “her beautiful, beautiful long body, so smooth, so white”. In the blank moments after death Sylvia sees “all her young beauty flooding back into her face” and puts her rosary in her hands. From Valentine, always a great bestower of gifts, there is a last, loving present: “on my desk … next year’s diary, inscribed by her”. On the page for May 20, Valentine’s birthday, three words in a firm, steady hand: Non Omnis Moriar.

The diaries that Sylvia kept between Valentine’s death and her own, almost twenty years later, have an uncanny, almost posthumous feel. There is a sense of a woman living in two worlds at once, an unreal, empty present and a past made authentic by love:

I inhabit my body like a grumbling caretaker in a forsaken house … Only two things are real to me: my love and my death. In between them, I merely exist as a scatter of senses …

Time and again, she is overcome by a sense of Valentine’s presence that goes beyond reverie or wish and verges on the mystical: “I held her again … this young creature who loved me … It was. It is.” After a day spent reading her 1930 diary, Sylvia is convinced that Valentine has followed her to bed: “a resurrection of the body … I believe”. And there is a night when Sylvia wakes at 3 a.m. and knows absolutely that she is not alone: “she was beside me in actuality of being: not remembered, not evoked, not a sense of presence. Actual.”

***

It is a common enough sadness to reach the end of a book and to wish there were more. In this case, the feeling is complicated by the knowledge that there is indeed more – a lot more. The one-volume selection from Sylvia’s diaries published in 1994 barely skims the surface of the 38 manuscript books held in the Dorset County Museum. A scholarly, multivolume edition is surely overdue, but with low brand recognition for the Warner name and the economics of publishing as they are, I’m not holding my breath.

This would probably not have bothered Sylvia. She does not seem to have been writing for posterity and told a friend that she thought the diaries “too sad” to publish at all. Any reader of the diaries will know exactly what she meant, but the final impression is not one of sadness; although there is deep, awful pain, the final impression is of a miraculous and undiagnosable joy. On what was probably the worst day of her life, the day she realized that Valentine would not be cured, Sylvia stepped outside, looked up at the sky, and saw something extraordinary: “I saw the Sun dance, as it’s said to do on Easter morning … I can hardly believe it. But I saw it.”

She had seen the sun dance.

very interesting indeed!