Judith Flanders is one of the leading historians of the Victorian period – and wrote a guest post on the Dabbler about the invention of detective fiction here. Today, Jonathon reviews her new book The Victorian City, Everyday Life in Dickens’ London…

Dickens is 200 this year and no one has ever delineated a city, in this case London, and its world better than did he. The word Dickensian can be found in the 1840s: it suggested the optimism and good cheer of the Pickwickians and the closing, goose-bedecked scenes of A Christmas Carol. Such was its meaning during the writer’s life. The 20th century changed the definition, turning it accusatory and focusing on the Scrooges, the Gradgrinds, and a social system that in its lodging of the poor – the workhouse – was first concerned to see that that such lodgings lacked ‘eligibility’, that is the tiniest vestiges of welcome and comfort. The truth, or at least the recorded facts, lies somewhere between the two. The historian Judith Flanders, who has already considered the minutiae of The Victorian House (2003) and what she suggests was the 19th century’s Invention of Murder (2011) now turns her skills to the larger world: London in the era of its greatest chronicler. She takes him as her guide, and his narratives – fact and fiction – drive hers. They are, however, but starting points for a book of absorbing, wide-ranging exploration.

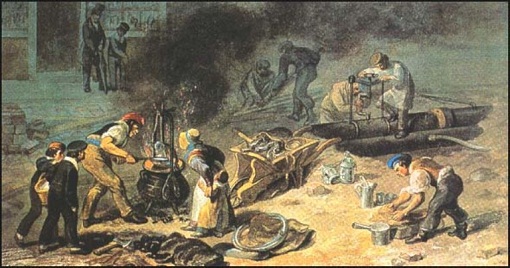

We know a great deal about Victorian London. The city was expanding, moving from its compact Regency boundaries to a vast metropolis spreading out towards rings of suburbs. The population grew at speed. More people, more needs. Dickens noticed, and Ms Flanders has followed his lead, embroidering the basics with wide-ranging and always revelatory material. Like the city itself, which left foreigners who had been used to far smaller capitals, both amazed and aghast at its enormity, it is impossible to encompass the full range of her work. She takes in public transport (including the material that makes up the streets beneath), the burgeoning railways that helped create those suburbs, the many markets whether large – Smithfield, Billingsgate, Covent Garden – or small and local, the slums – St Giles and Fagin’s Saffron Hill – the stinks and stink industries, the impenetrable brown fog, the sewers – both before and after they were properly added to the urban infrastructure – the food and entertainment available on the street and the violence that one might meet there (not to mention a new take on advertising: the sandwich man), the language (including slang), and the nightlife, both respectable and, typically in prostitution, less so. This is merely to enumerate her chapter headings: the gods of this historical overview truly lie in the detail.

Ms Flanders is of course hardly the first explorer. She displays an impressive bibliography and draws on it with verve. Nor is she alone today. The Internet is filled with a variety of historians, professional and amateur, who are walking those Victorian by-ways. The material seems inexhaustible. The Victorians did it themselves. Henry Mayhew then James Greenwood are perhaps the best known of these prototype ‘social scientists’. But her primary guide, Dickens, emerges as the greatest. What is underlined is what we know from his many biographers, but not usually broadened out with so much evidence: the extent to which his fiction is informed by the material that his reporting, the fruit among other things of his near obsessive walking of London’s streets, discovers. If he created ‘his’ London, the mid-Victorian London that dominates all our images, then he did it from fact, not fantasy.

Ms Flanders does not take all at face value. She dissects her evidence and often challenges its assumptions. The sardonic wit that on occasion pops up in The Invention of Murder (and for the pleasure of those who follow her on Twitter) is present here; her politics, unless I misread her, are unashamedly liberal. Commenting on the reluctant and belated committal of state cash for efficient sewerage she notes the arrival of the ‘Great Stink’ in the Houses of Parliament and adds ‘Nothing makes funds available more quickly than the discomfort of the ruling class.’ Her take on prostitution, among much else that was seen as the ‘inevitable’ fate of the allegedly ‘idle’ and ‘criminal’ poor, is nuanced. She deconstructs the generalizations offered by Mayhew – or rather those of his less than well-qualified collaborators to whom he turned over the subject – and gives, perhaps surprisingly, a good deal more credence to ‘Walter’, he of My Secret Life, than one might normally find.

Like Mayhew and Greenwood she writes with compassion. She needs to, because while there are an infinity of delights, this is not ultimately a cheerful book. To note that even the section entitled ‘Enjoying Life’ finds itself prefaced by a discussion of the 1867 Regent’s Park Skating Disaster (40 dead), is perhaps to tease, but the world of the one and the ninety-nine per cents is not an invention of the 21st century. There may have been slumming, but there was little understanding of one class by another. For the majority life was tough, with no social trampolines: one could fall far and fast (and rise thus too as Dickens regularly points out) and the willfully cruel hypocrisies of Evangelism, underpinned by a Queen who descended into mourning and effective absenteeism for the last half of her reign, did not help. Even Dickens, however sympathetic, tends to draw his working-class characters in overly-stereotyped tones; it would take the ‘Cockney novelists’ of the late century to make some effort to look objectively at the poor.

As she has already proved, Ms Flanders is a mistress of the historical marshalling yard, assembling her vast selection of information in ways that cannot fail to enthrall her readers. Anecdotes, memoirs, diaries, letters, court and press reports, governmental blue books, bawdy songs… It is an omnium gatherum, a gallimaufry, an olla podrida. It offers the richest, juiciest, most plum- and sixpence-stuffed of Dickens’ Christmas puddings. It is a glorious, if sometimes terrifying and often distressing raree-show. It is wholly fascinating.

That;s interesting about the changing meaning of ‘Dickensian’. Could there be any higher compliment to an artist that he become an adjective? And in this case, an adjective twice over.

Of course, 100 years from now, any torrent of highly erudite and eloquent filth shall be known as ‘Greenian’.

I must say I am interested in this book – for reasons that you allude to JG, I follow Judith on twitter and she comes across just as you say. If a hint of her personality comes across in the book then I’m sure it would be a good read, even if it is well trodden subject matter. This one’s going on my amazon list