Having recently demolished some of the most popular football myths, James Hamilton begins another three-part series for our Row Z feature, this time looking at death and violence in Victorian and Edwardian football. The first part reveals that football fan violence was far from an invention of the Thatcher years…

It’s one of the most extraordinary and tantalizing facts of our time. Take out all the estimated-to-be-drug-related activity out of the crime figures, and what you are left with are the gentle, pacific, Marpleian levels of fair-cop crime enjoyed in 1920s and 1930s Britain.

They didn’t enjoy them in the Edwardian period! Here’s Bolton v Glossop, Division Two of the Football League, 1908:

“No fewer than three players were sent off the field during the game, which was admittedly very vigorous indeed. Cuffe was the first sent off, and then a stand-up fight took place, with the result that Marsh and Hofton were ordered off. The referee was Mr. W. Gilgryst, and he reported the clubs to the Association, and also the players. He says, too, that the spectators were most rowdy and threatening during the greater part of the game. Mr. Gilgryst had to be escorted from the field to the dressing-room by the police and others, and was struck a severe blow from behind, the offender being taken in to custody. Furthermore, an official of the club was reported for using filthy language and for abusive conduct, while Bolton players complained of rough treatment. I am afraid there is serious trouble.”

(John Cameron writing for the Penny Illustrated Paper)

The best early stories of this kind always seem to involve fans of Preston North End. They knock railway officials unconscious at Wigan station in 1881. In 1884, they attack Bolton Wanderers players and fans at the end of the game. In 1885, they are involved in a stave fight with their colleagues from Aston Villa. In 1886, they take on Queens Park (Glasgow) fans at an unnamed railway station and two years later, there are tales of a hail of bottles..

In the 1890s, Preston step to one side and leave the field free for West Brom, who, at an away match with Nottingham Forest, invade the pitch and attack their own players!

It’s very hard to know exactly what is going on in stories like this. Part of the problem is that, contrary to what many might assume, we don’t really know much about who it was that was going to football matches. What evidence there is, is contradictory. One early Mitchell and Kenyon film of Nottingham Forest’s ground, scene of the Baggies triumph I’ve just described, shows a seated stand full of what are very obviously well-dressed, prosperous gentlemen and ladies. Other grounds that Mitchell and Kenyon feature really are all flat-capped, but most crowds are more varied and more difficult to judge. Ibrox was built in a genteel area and hoped to attract a loyal local following.

We do know that football clubs and authorities took measures to restrain crowd violence and regarded it as a problem – the “two-headed hydra” of the game, as one Victorian observer put it. Troubled grounds could be ordered closed, and matches moved. The Football League imposed a minimum entrance fee of 7d, pricing out the poorest (and, it was assumed, the most unruly). Most clubs charged even higher entrance fees for certain of their enclosures. Some seats at Old Trafford when it opened in 1910 were at a price point of several shillings.

It’s interesting to note that off-duty soldiers and naval men were granted free admission, on the premise that they would intervene to help out if trouble arose. That speaks of a belief in a cooperative, people’s policing in which the responsibility for order and control was more widely spread than it has become.

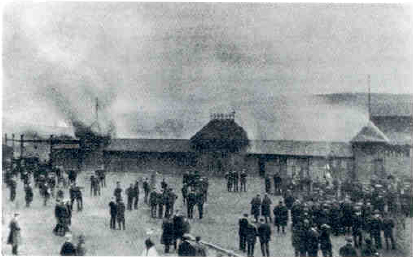

We also know that in common with all Edwardian crime measures, the amount of crowd violence declined in the years up to 1914. The climax seems to have been the great Hampden riot of 1909, in which 6,000 people participated, the pitch was destroyed and many parts of the stadium badly damaged by fire.

We’d see nothing like that again for another sixty years. It’s been said that the crime rates of interwar Britain are both the best any comparable country has ever enjoyed, and the hardest for any comparable culture to explain. So it was with football. Fan violence went away for forty years after 1919. And we’ve no real idea why.

This goes well with Gaw’s anti-nostalgia post yesterday. “A stave fight” sounds rather quaint at this distance, but ‘quaint’ probably isn’t the word you’d use if you found yourself at the wrong end of a stave…

In one respect, puzzling but possibly a piece of the jigsaw that is Dave’s big society has been solved, every now and then, don uniforms, nip across to Flanders and have at the Bosch, sorted, Millwall becomes a haven of pacifist calm.

Observed violence, or lack thereof, may be in the eye of the beholder and subject to partisan colouration, taken to watch second division Elche play in their large all-seater, easy-to-park-outside-of stadium I was told “never get any crowd trouble here you know, much more civilised, the Spaniards”. Yeah, right, 10mins in some Pedro accurately hurls a full can of beer which bounces off the ref’s napper, rendering him horizontal. Leading to the conclusion that A..the ex pat was ex brains or B…the violence, as he said, wasn’t in the crowd but was an interaction between the crowd and the pitch.

Naturally after that little incident the vibes among the crowd hoisted themselves up onto an altogether different level, what a waste of beer.

Or maybe, Eche or Elix as was, being the old Roman part of Spain, the locals thought the ground was a Flavian Amphitheatre.

“Keano! Keano”. Fred Keane, that is – Preston wing half, 1899 to 1905, always in the face of referees, dismissive of the cucumber sandwich set; hero of Deepdale’s whippet loving, flat cap brigade. He was infamous for inciting violence among visiting Bolton fans by parading in front of them, holding his nose, with a string of five year old pigs’ trotters (Bolton’s iconic symbol) round his neck. No wonder Preston had such a bad reputation.

Remarkable to think that the authorities assumed that off-duty naval men would intervene to prevent trouble, rather than being the ones starting it…

Brit, as I understand it, this ‘volunteer to thump a hooligan’ idea was an important part of Arthur Balfour’s ‘Big Society’ concept.

From memory, Gregory Peck’s character in The Big Country was a retired naval man, gentle as a lamb, without a Colt 45.

James description of Ibrox / genteel area is thought provoking, today it is a big brick box midst a sea of desolation, just around the corner is Media City, hub of the Scottish entertainment industry, the Ku Klux Klan meets Bollywood. Further around the corner is the big tin box that is BBC Scotland. Sort of the Ku Klux Klan meets Bollywood meets The Guardian’s audio visual outpost in the north.

It’s always deceptively charming when the hardest nuts of a bygone age are called Fred and Arthur (GAW’s post yesterday). Football was the only thing my grandfather (also an Arthur) enjoyed – that and Max Bygraves – and would never have dreamed of making any trouble worse than commenting “Where’s your specs, ref!”

Apparently, the violence was so pervasive that the words in the song: “a policeman’s lot is not a happy one” were spot on, with coppers being knocked senseless on a daily basis.

James refers, in his wonderful piece, to Mitchell and Kenyon. I suppose the cinematic recording of violence and mayhem was not what M and K felt was wanted; their audiences were too busy sprucing themselves up to be filmed for the sunday promenade, the parade to celebrate England’s glory, even to be caught with a smile on leaving the factory after a filthy, dangerous, and deafening 14 hour shift. The smiles were probably buffed up with an oily rag. Whenever I watch the glorious ‘Electric Edwardians’, I sit, almost trance like, beguiled by the astonishing clarity of those images of long dead people. Perhaps seeing them on best behaviour is the way it should be; I can watch a bunch of hooligans kicking a ball about whenever United play Liverpool.

Yes, I think you’re right, John: M&K would have had little interest in filming something unless it couldn’t earn for them later in the day/week at the local temporary cinema. It’s an interesting difference between the news and popular cultures – since the 1950s, the stress has shifted away from crime/violence being the exception in an otherwise jolly nice country, towards being the “secret truth” behind the false facade. Personally, I think we’re the ones getting it wrong.

But there are SOME M&K films that aren’t like this. I’ll try to find which ones and if any are online. One I recall from Dan Cruickshank’s series – men leaving a metalwork factory very obviously filthy, miserable and exhausted – a local brewer has sent a wagon to sell them beer as they emerge, and he’s doing brisk business. Another is taken in the yard of some utterly benighted looking factory, and the fight in this one isn’t, for once, concocted by the filmmakers, but real and threatening: the cameraman beats something of a retreat. It’s a horrible 2 minutes to sit through.

I agree completely with your first para, James. Regarding the scene of real violence you refer to in the second, I don’t recall seeing it, but will check if it is included in ‘Electric Edwardians’.

I also own the DVD and will see if I can identify it. It’s a handbags sort of fight, but definitely real and not inspired, as were so many others, by M&K themselves. Look for the handkerchief being waved from a window at the end, which the commentators (if I’m remembering this correctly of course!) identify as a signal to wrap up.

Found it..

The “fight” comes from the grim and atmospheric “Parkgate Iron and Steel, Rotherham 1901” which is Youtubed for the curious.

The “other” film – of exhausted men falling onto a beer wagon – is on the Dan Cruickshank “Lost World of Mitchell and Kenyon” DVD, complete with the entirely apposite and outraged comments of an employee’s grandson.

I think a consequence of having a more egalitarian society is that public violence tends to become ‘our’ problem, rather than something perpetrated by those outside respectable society who can be dismissed as knowing no better.

BTW another great post!

Thanks, James, it is fascinating; one almost gets an impression of M and K experimenting with a far less structured approach, in some ways spontaneous and unannounced (to the workforce). The men look to have one thing in mind: home. The fight does look genuine. The whole scene has a menacing quality. Were the handkerchiefs prompted by a works manager warning M and K that it would be wise to stop.

We might, perhaps, expect a Carl Davis soundtrack played by the LSO as an accompaniment to the films, but the music provided by ‘In The Nursery’ seems so apt.