A master of vicious social satire, E. F. Benson was just one member of a powerhouse Victorian literary family that is now all but forgotten. But his Mapp and Lucia novels are immortal…

This article by Andrew Nixon (aka Dabbler founder ‘Brit’) first appeared in Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly, Issue 54, Summer 2017 under the title ‘First-rate Monsters’. Slightly Foxed have kindly allowed us to publish it here.

E. F. Benson’s Mapp and Lucia books ruined Beethoven for me, and very nearly Shakespeare too.

Picture, if you will, the most appallingly pretentious person in the world: a well-dressed middle-aged lady at the piano, plonking her way through the slow first movement of the Moonlight Sonata. She is wearing her ‘well-known Beethoven expression’ with the ‘wistfully sad far away look from which the last chord would recall her’. Her guests, enduring the entertainment in various attitudes of suicidal boredom, give dutiful little sighs as that last chord fades, and then steel themselves for . . . another rendition of the slow first movement of the Moonlight Sonata! For – though she pretends otherwise and that Beethoven composed the trickier second movement largely by mistake – it is in fact the only tune she can play.

This is Emmeline Lucas, aka ‘Lucia’, and I’ve not been able to enjoy the Beethoven sonata since meeting her. The Italian affectation of ‘Lucia’ is just that, since she has no connection with Italy and certainly doesn’t speak the language. But by peppering her conversation with plenty of mio caros and molto benes she permits it to be thought that she is quite fluent in la bella lingua.

I’m afraid it gets worse. The bedrooms in Lucia’s house have names like ‘Othello’ and ‘Hamlet’. In the garden there is ‘not a flower to be found save such as were mentioned in the plays of Shakespeare’. And the flowerbed beneath the dining-room window is known as ‘Ophelia’s border’.

In Queen Lucia (1920) this stellar snob lords it over the village of Riseholme, oppressing local society with her profound appreciation of Shakespeare, her merciless Moonlights, her smattering of Italian and her unrelenting energy. Then in Lucia in London (1927) she deploys these same weapons to conquer the capital.

Yes, Lucia is a ruthless social climber, a backstabber and a perfectly shameless pseud. But the funny thing is that, through the series of novels that follow, we the readers are generally on her side. And that’s because a little distance away, in a picturesque East Sussex town, there lurks somebody far, far worse . . .

***

‘Elizabeth was gazing out of the window with that kind, meditative smile which so often betokened some atrocious train of thought.’

From the garden room of Mallards, her ancestral home, the eponymous anti-heroine of Miss Mapp (1922) plots against her friends and neighbours. The garden room is important: it is a strategic vantage point affording clear views down the two principal streets of the town of Tilling, so she can chart all comings and goings in comfort.

Tilling is a lovely, chocolate-box sort of place, with cobbled streets and characterful houses inhabited by the archetypes of the interwar leisured class: vicar’s wives, ageing spinsters, retired colonels. It is Elizabeth Mapp’s great purpose to devise new and ingenious ways to make their daily lives slightly less pleasant than they would other-wise be, and to ensure that the round of garden parties and bridge evenings that is Tilling’s social scene remains a hissing snake pit of envy and resentment.

The chief weapons in her armoury are thinly veiled sarcasm and cutting criticisms disguised as compliments. True, she is not the only culprit in the town’s never-ending social war. The women of Tilling have, as one male character ruefully puts it, ‘a pretty sharp eye for each other’s little failings’ (though the men are just as bad). But Mapp is by far the most ruthless and skilled operator. Hers are ‘the most penetrating shafts, the most stinging pleasantries’, and thus she is feared and admired by all.

Large and toothy, her face is ‘corrugated by chronic rage and curiosity’. She terrifies local shopkeepers and tradesmen with continual niggling disagreements:

Quarrelsome errands were meat and drink to Miss Mapp: Tuesday morning, the day on which she paid and disputed her weekly bills, was as enjoyable as Sunday mornings when, sitting close under the pulpit, she noted the glaring inconsistencies and grammatical errors [in the sermon].

In short, she is a master of what we might now call ‘passive-aggressive’ behaviour: never quite saying anything unambiguously insulting, but still making sure that everyone in the room feels jolly uncomfortable.

Like Lucia, Mapp is a first-rate monster, vivid and fully realized. Had their creator, E. F. Benson, left off at Miss Mapp, he might still have earned a respectable middling position in the pantheon of English observational comedies. But, fortunately, he hit upon the one indisputably great idea of his career, which was to elevate him to the top rank and preserve his name for posterity: he brought his two monsters together.

If you are a first-time reader of E. F. Benson, I urge you to start with Miss Mapp and the two ‘solo’ Lucia novels and work your way towards Mapp and Lucia (1931), rather than diving straight into the most famous volume in the series. The steadily growing prospect of these two titanic female egos meeting each other is quite thrilling, and conjures thoughts of unstoppable forces and immovable objects.

The wheeze Benson cooks up is that Lucia – newly widowed but with her chaste companion Georgie in tow – comes to Tilling to rent Elizabeth Mapp’s house for the summer. The latter doesn’t leave town: an eccentric local tradition sees the residents all holidaying in each other’s homes, meaning that Mapp is ever available to ‘pop in’ with helpful advice, to keep an eye on how her beloved Mallards is being mistreated, and generally to try to ‘run’ Lucia in the Tilling social scene.

Alas, she soon finds that her tenant is not the sort of person who can easily be run. (‘I see I must be a little firm with her,’ thought Lucia, ‘and when I’ve taught her her place, then it will be time to be kind.’) Worse, Lucia emerges as a clear threat to Mapp’s position as dictator of Tilling. She trumps Mapp’s teas with dinner parties, turns her own Mallards against her by hosting lavish garden parties and beats the locals into submission with the Moonlight.

Hostilities commence early and escalate rapidly. Mapp fires her most stinging pleasantries; Lucia combats them with retorts of ‘paralysing politeness’. Before long they are locked in a deadly war of attrition with first one then the other gaining the upper hand. The war doesn’t let up through the rest of the novel or the sequels, Lucia’s Progress (1935) and Trouble for Lucia (1939).

These three books are masterpieces of social satire and a joy to read. They’re vicious and gripping and wickedly funny, and they remain so after repeated rereading. They’re also about as deep as a puddle.

***

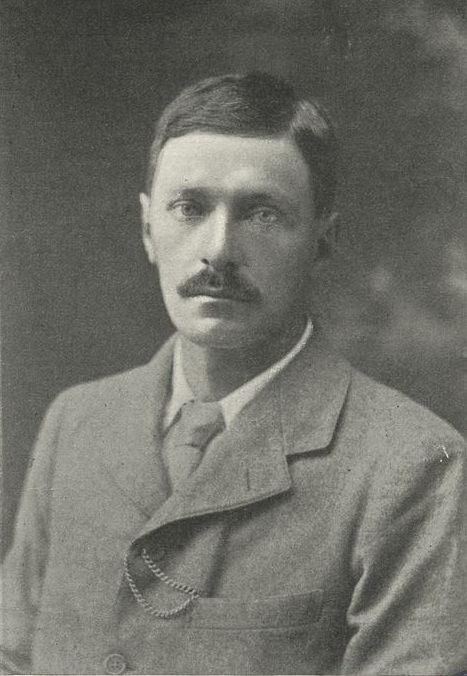

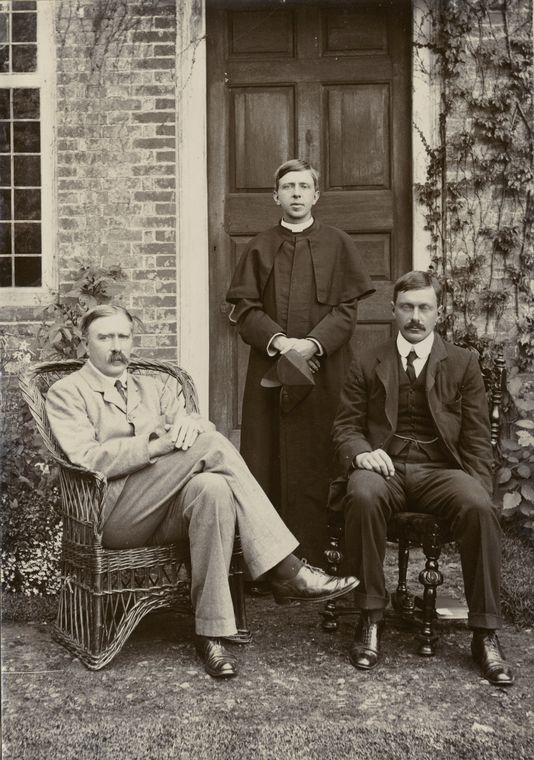

Posterity is a curious thing. Edward Frederic (‘Fred’) Benson (1867‒1940) was, from one angle, a rather frivolous odd-man-out in a very serious literary family. His father was a giant of the Victorian age: the domineering, humourless Edward White Benson, first Headmaster of Wellington College, first Bishop of Truro (where he invented the Christmas service of Nine Lessons and Carols) and later Archbishop of Canterbury. Fred’s elder brother Arthur was Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge, and a heavyweight essayist and prolific diarist who composed the lyrics to ‘Land of Hope and Glory’. Their younger siblings Robert Hugh and Margaret were respectively a pioneer of dystopian fiction and a celebrated Egyptologist. Literature simply poured out of the Bensons. At Christmas their favourite parlour game was to write pastiches of each other’s work. Fred himself published close to a hundred books in all conceivable genres from ghost stories and memoirs to sporting history, by way of serious fiction. Yet of all the countless millions of these combined Benson-written words, almost nothing is still read today except Mapp and Lucia.

The young Fred would have been appalled at such a legacy. Much of his literary life was spent trying to write something weighty enough to escape the shadow of his own first novel. Dodo (1893) – a sensational, smash-hit melodrama about a social climber – was openly disdained by his father and elder brother. In pursuit of gravitas he published several important works on archaeology as well as biographies of Sir Francis Drake and Charlotte Brontë. But try as he might, in the public mind Fred remained the creator of the eponymous Dodo . . . until he came up with the even more outrageous social climber Lucia. For all his efforts he was destined to be remembered for a handful of comedies of middle-class manners.

Then again, from another angle Fred’s achievement is admirable, even triumphant. There was a dark side to the Bensons. The patriarch Edward White had proposed to his cousin Mary Sidgwick (‘Minnie’) when he was in his mid-twenties and she was just 11 years old. Their weird, virtually arranged marriage took place six years later. The tensions within the family were awful. Of the six children Minnie bore, one died and at least three suffered from severe mental illness. None produced offspring of their own; they were almost certainly all non-practising homosexuals (as indeed was Minnie: after she was widowed she happily cohabited and shared a bed with Lucy Tait, daughter of the previous Archbishop of Canterbury). Arthur was plagued by manic-depressive psychosis, Robert Hugh had a catastrophic entanglement with the notorious fraudster Frederick Rolfe (‘Baron Corvo’) and Margaret ended her days in the Priory after succumbing to a ‘violent homicidal mania’.

Throughout all this, Fred led a remarkably sanguine and benevolent existence. In contrast to his insular siblings he was sociable and well-rounded. He was a gifted sportsman, spending his winters ice-skating to championship standard and his summers relaxing on the island of Capri. He knocked out bestselling books without much apparent effort. In the last part of his life Fred settled in the East Sussex town of Rye, eventually becoming the town’s mayor and living in Lamb House, the former home of his friend Henry James. From there he quietly, selflessly gave emotional succour and financial support to the suffering Arthur and Margaret.

And, of course, he fictionalized Lamb House as ‘Mallards’ and Rye as ‘Tilling’ and populated them with a cast of unforgettable caricatures, of whom Mapp and Lucia are merely the most vivid. Others include the camp bachelor Georgie Pillson, with his daring trousers and precious cabinet of ‘bibelots’; the Reverend Bartlett who, despite hailing from Birmingham, talks in ‘a mixture of faulty Scots and spurious Elizabethan English’; and the Bohemian artist ‘Quaint’ Irene, who wears men’s clothes and is always doing preposterous arty things (‘she sat for half an hour at Lucia’s piano, striking random chords and asking Lucia what colour they were’). Far from feeling insulted by these parodies, it seems that the locals of Rye were all eager to claim credit as their models.

While the rest of the wider Benson canon slides deeper into obscurity, Tilling remains in rude health. Various novelists have written follow-ups, a Friends of Tilling Society counts Gyles Brandreth and Alexander McCall Smith among its patrons and is active on Twitter, while a terrific BBC adaptation was made as recently as 2014.

In the Mapp and Lucia books Fred Benson’s prose is effortlessly entertaining. The satire is clear-eyed, drained of any delusion about human nature, but not entirely unforgiving. Above all else, it is very, very funny. His command of twisty witticisms (‘paralyzing politeness’, ‘vindictive forgiveness’) is second only to Wilde; his construction of farcical situations in which middle-class snobs get their come-uppance, second only to Wodehouse. As a dissector of the timeless human qualities of bitchiness, cattiness and vacuous viciousness he is quite without peer.

For as long as there is society and snobbery there will be Lucias and Mapps. They are, therefore, probably immortal. Posterity is a curious thing, but perhaps Fred Benson’s legacy isn’t such a bad one in the end. It’s just a shame I can’t listen to the Moonlight Sonata any more.

© Andrew Nixon, Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly, Issue 54, Summer 2017.

The independent-minded quarterly that combines good looks, good writing and a personal approach, Slightly Foxed introduces its readers to books that are no longer new and fashionable but have lasting appeal. Good-humoured, unpretentious and a bit eccentric, it’s more like a well-read friend than a literary magazine. Single issues from £11; annual subscriptions from £40. For more information please visit www.foxedquarterly.com