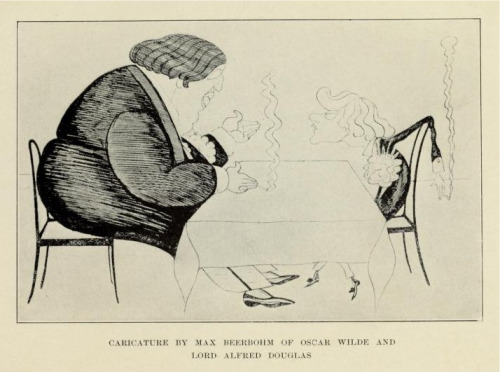

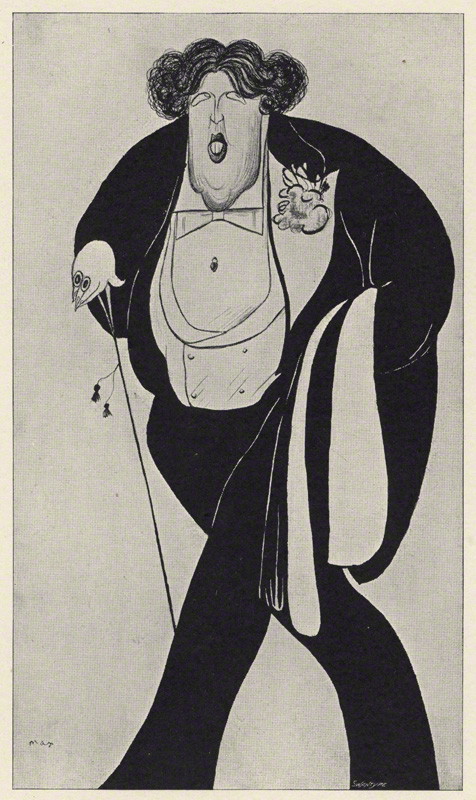

Nige uncovers a remarkable piece of precocious satire: a young Max Beerbohm sticking it to an Oscar Wilde at the peak of his powers…

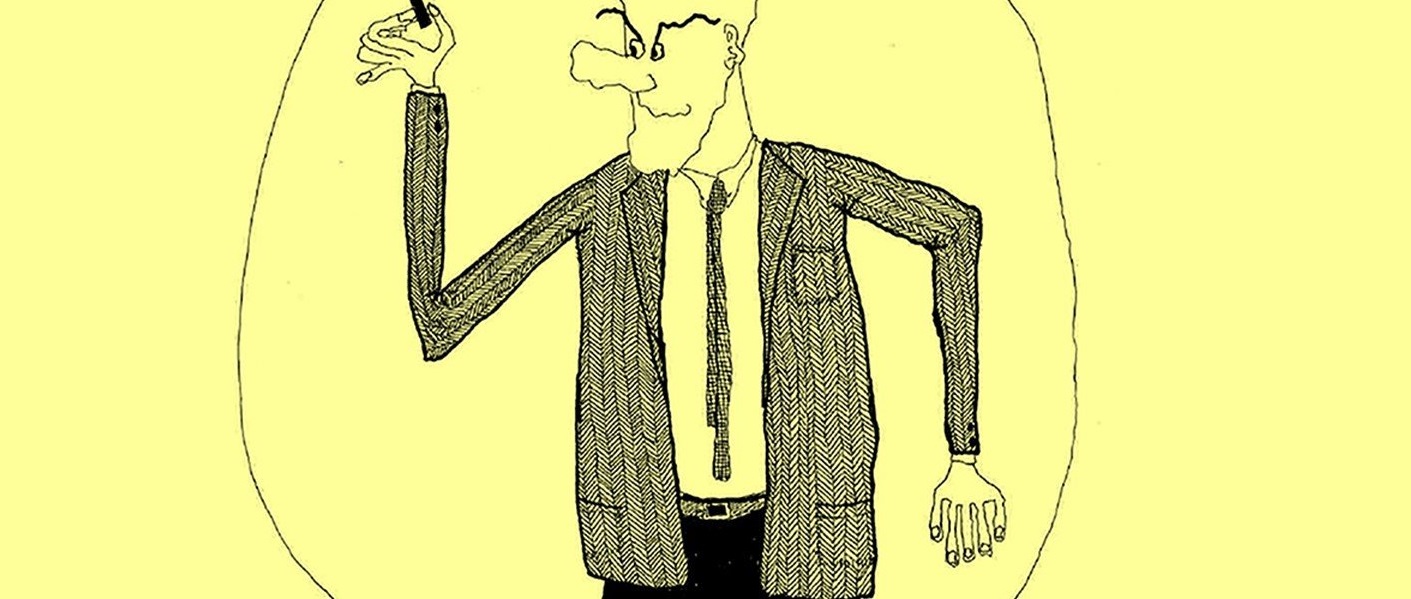

Browsing my overcrowded bookshelves with a view to some thinning out, I came across a collection of previously uncollected pieces by Max Beerbohm, A Peep into the Past (Rupert Hart-Davis, 1972) – definitely a keeper.

The title essay is a quite extraordinary piece, written in 1893/4, when Max was a 21-year-old undergraduate, and apparently intended for the first issue of the Yellow Book (where, in the event, Beerbohm was represented by A Defence of Cosmetics). A Peep into the Past projects an alternative reality in which Oscar Wilde is an elderly, all but forgotten belle-lettrist, living ‘a life of quiet retirement in his little house on Tite Street with his wife and two sons, his prop and mainstay, solacing himself with many a reminiscence of the friends of his youth’.

‘Oscar Wilde!’ begins Max…

I wonder to how many of my readers the jingle of this name suggests anything at all? Yet, at one time, it was familiar to many, and if we search back among the old volumes of Mr Punch, we shall find many a quip and crank cut at its owner’s expense. But time is a quick mover and many of us are fated to outlive our reputations and thus, though at one time Mr Wilde, the old gentleman of whom we are going to give our readers a brief account, was in his way quite a celebrity; today his star is set, his fame obscured in this busy changeful city.

Bear in mind that this was written when Wilde, then 39, was at the peak of his fame – just a year before it all ended in scandal and ignominy.

Mr Wilde, we are told, is an early riser and an indefatigable worker, with ‘an infinite capacity for taking pains’ and plenty of ‘”grit”, as they call it in the North’…

Himself most regular in his habits, he is something of a martinet about punctuality in his household, and perhaps this accounts for the constant succession of page-boys which so startles the neighbourhood.’ This is not the only hint at Oscar’s predilections: when the author ventures to pay a visit to the house on Tite Street, ‘I found everything there neat and clean and, though of course very simple and unpretentious, bearing witness to womanly care and taste. As I was ushered into the little study, I fancied that I heard the quickly receding frou-frou of tweed trousers, but my host I found reclining, hale and hearty, though a little dishevelled, upon the sofa. With one hand readjusting the nut-brown Georgian wig that he is accustomed to wear, he motioned me with a courteous gesture of the other to an arm-chair…

Beerbohm constructs an alternative literary career for Wilde, in which he has published little under his own name, produces quantities of journalism, and finally writes a play when already in his old age. ‘After all,’ Max sums up indulgently, ‘it is not so much as a literary man that Posterity will forget Mr Wilde, as in his old capacity of journalist.’ (Note ‘forget’.)

The visit to Tite Street goes well enough:

The old gentleman was unaffectedly pleased to receive a visit from the outer world, for, though he is in most things “a praiser of past times”, yet he is always interested to hear oral news of the present, and many young poets can testify to the friendly interest in their future taken by a man who is himself contented to figure in their past…

Wilde’s celebrated wit is represented by a mangled version of a famous exchange with Whistler, in which

Wilde, beaming kindly across the table, said, to encourage him, “How I wish I had said that!” Young impudence cried, “You will, Sir, you will.” “No, I won’t,” returned the elder man, quick as thought…

Then, at the end, comes an equally painful example of Wildean paradox:

Just as I was leaving the room I observed that the weather had become very sultry and I feared we should have a storm. “Ah yes,” was the reply, “I expect we shall soon see the thunder and hear the lightning!” How delightful a perversion of words! I left the old gentleman chuckling immoderately at his little joke.

A Peep into the Past reads now like a strange kind of reverse prophecy, the projection of a future that could scarcely be more different from the one that actually unfolded for Wilde. Did Max sense something frail about Oscar’s fame, the possibility of terminal disaster?

The least surprising thing, perhaps, is Beerbohm’s ability, while still an undergraduate, to project himself as a staid, middle-aged, genteel literary essayist: as Wilde remarked, Max was blessed with the gift of perpetual middle age.