As a couple more Labour leadership contenders drop off the greasy pole, Terry Stiastny, author of political thriller Acts of Omission, disinters a blisteringly cynical fictional account of the political life, and wonders why they bother in the first place.

It was so comfortable to be out of the race.

Then again, he thought, he would have faced a new and refined torture if he had become an Under-Secretary. The ladder would have stood before him as a constant challenge. He would have jostled against the press of his equals for a place on the next higher rung. Each parliamentary speech would have been an ordeal because failure would have raised the spectre of the sack. And each success by his rivals would have bred jealous despondency. He was lucky to be out of it. Now he could relax on the sidelines and watch the others sweat it out.

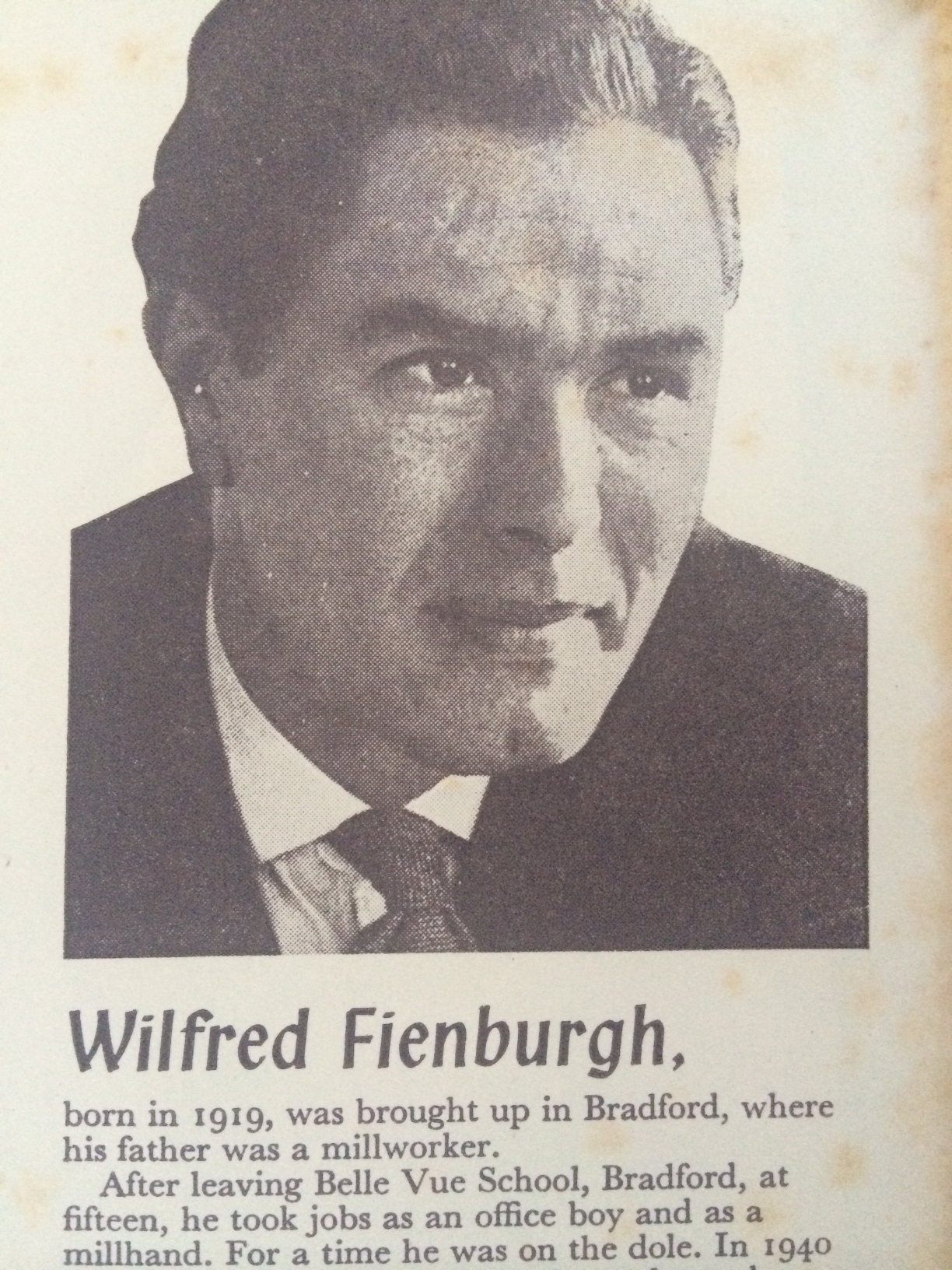

This is not Chuka Umunna in 2015, nor is it Dan Jarvis. This is the fictional Labour MP, Johnnie Byrne, in 1959, a political rebel without a cause. Byrne’s creator was a real Labour MP, Wilfred Fienburgh, who died in a car crash, aged thirty-eight, before his only novel was published. The book, No Love for Johnnie (you can buy it here), is mentioned in David Kynaston’s Modernity Britain, where Kynaston quotes Harold Macmillan’s view of the book’s publication; that if Fienburgh ‘hadn’t died, the other Labour MPs would have killed him.’

The angry young MP of the story is not great leadership material. Resentful at being passed over for promotion, he takes to drink and an affair. He picks a Middle Eastern conflict over which to cause a rebellion, hoping to win success that way, but, distracted by a woman, forgets to turn up to ask the crucial Commons question that would trigger the revolt. He is dilatory, never replies to his constituents’ letters or turns up to surgeries. It’s a laziness that a modern MP would find it much harder to get away with.

From the book’s opening lines, we are introduced to Johnnie’s bitter and jaded view of his own political career:

I wish I were a hundred miles away from this railway carriage, thought the Member of Parliament. The speech I am going to make is stuck in the back of my throat. I am choked by the dry dust of a thousand speeches. I am weary of words and hand-shaking and smiling at people and screwing myself up to mouth platitudes. There is nothing new to say. The whole damned business is as mechanical and meaningless as a formal tribal dance.

Even to modern ears, this is blisteringly cynical — or perhaps just blisteringly honest. If not going as far in public as Macmillan thought, other Labour figures, such as Richard Crossman, who called the book a ‘nauseating caricature’, were dismissive. Byrne, however, is also concerned with his image, his press coverage. He provides a running commentary on his own actions by imagining how they will appear in print.

Wilfred Fienburgh seems to have been as roguish as his fictional alter ego: contemporaries noted his love of well-placed gossip; Denis Healey said Fienburgh’s ‘good looks and big brown eyes’ led him astray, and described his ‘pretty wit’. Addressing the Spiritualist Association, Fienburgh was asked what the late Keir Hardie would have thought if he’d known the Witchcraft Act was still in force. ‘Why don’t you ask him?’ he retorted. Healey believed Fienburgh might have lived to be a leadership candidate, if it weren’t for the ‘demon’ that made him ‘accident-prone’. He’d have been great on Twitter, but then we’d probably also know precisely where those big brown eyes led him.

It’s hard to know whether a modern Fienburgh would charm the public or be destroyed by public scrutiny, or ultimately both. We say we want our politicians to ‘speak human’, to be human, but then snigger unforgivingly at their student photos, whether nerd or toff. The strain that politics puts on those who enter it isn’t just down to the media; it’s partly the long hours, the distance from family and home. The Conservative MP Charles Walker estimated that one in six of the Tory MPs in the 2010 intake had seen their marriage or partnership break up. No wonder that weighing ‘the rest of your life’, in Chuka Umunna’s words, against politics, often tips the scales towards life.

This isn’t to argue for a return to deference, to the ‘is there anything you’d like to say to the nation’ style of interviewing, or to the days when the abuses of a Cyril Smith could be covered up. French politicians, for instance, have tended to abuse their rights to privacy not only to hide affairs but more importantly, to conceal financial scandals. We need to know when politicians are breaking the rules that apply to all of us. But maybe, if we want them to be more like normal human beings, we could sometimes cut them the same slack we do to the human beings we know.

Terry Stiastny’s Acts of Omission, winner of the Paddy Power Political Novel of the Year, is now available in paperback.

I haven’t read the book, but I can thoroughly recommend the film adaptation, starring the wonderful Peter Finch.

“If they can’t stand the heat, stay out of the kitchen,” was my mothers summation of the plot, upon her return from South Shield’s Savoy cinema. Her take on politics was firm and fixed, having mixed it with Ellen Wilkinson during her wartime career. That summation is as close to the truth today as it was then, the world of employment is awash with stress inducing scenarios, regardless of the name on the office door, why single out politicians for a bit of a cuddle. The problem, one of carrying out important work whilst being poorly paid, is the elephant in the chamber, rubbish in, rubbish out. Pay them the going rate then hurl the kitchen sink at them when clangers are dropped.

Sounds like an interesting book.

Im still wondering what Chuka got up to, not that I care one iota whether an mp did something ‘quirky’ in their younger days before becoming a politician

I haven’t seen the film but must try to track it down. The BFI recently put it in its top 10 films on British politics. Plus, it has Stanley Holloway in it.

A few nights after the general election, I happened to find myself in a sauna with a Government Minister (God I’ve been longing to use that line). I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone look so exhausted — or so depressed.

Until a week or so ago I’d barely heard of any of the Labour leadership contenders, and I’m still finding it hard to work out what they are supposed to stand for. Contrast that with the leadership election in 1976 — the first I can remember — when the candidates were Callaghan, Healey , Foot, Jenkins, Benn, and Crosland: massive figures whatever you think, with who knows how many Cabinet posts between them. Two things about that list are bound to strike you, from today’s perspective: (1) the average age must have been about 60; and (2) not even a token woman. The ideological differences were also very real and very sharp. Despite all the talk about Blairites and Brownites, I can’t help feeling that this is a distinction that will mystify future historians, at least in policy terms (the narcissism of small differences?).