They don’t make bad poets like they used to, laments Douglas Dalrymple…

It’s a sad truth not often recognized that the glory days of bad poetry – no less than the glory days of good poetry – are behind us. In the dewy springtime of bad verse a sorry line or a limp sonnet was received with joy. “Dalkey, you know, has written a truly rancid couplet,” you might say to a friend over coffee in 1781, and he would foam at the mouth till able to confirm it for himself. In our own benighted era, the best that Dalkey’s great-grandson can manage to elicit is a shrug or a fart.

The trouble is not that people no longer write poetry. A casual browser of blogs today may be tempted to conclude that the Internet exists primarily to facilitate the distribution of amateur verse. It’s nose-deep in the fervid free-verse emotings of approximately 1.6 billion teenage poetesses and balding, fifty-year-old beta males. But none of them is worth reading. None is sufficiently terrible, or terrible in the right way. Verse published offline suffers the same curse: none of it is especially good, but none of it is bad enough to be anything very special.

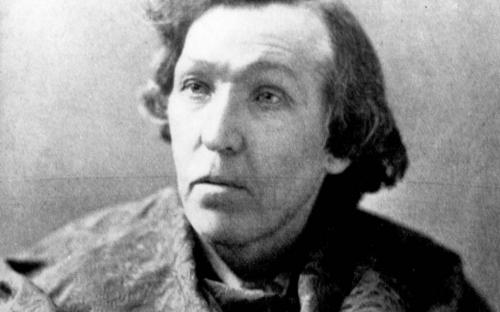

The patron saint of awful poets is William Topaz McGonagall, the “Tayside Tragedian,” born in 1825. Stephen Pile in The Book of Heroic Failures writes that McGonagall was “so giftedly bad he backed unwittingly into genius.” Memory of that genius was so pungent and enduring that more than a half century after his death he inspired a bit-character on The Muppet Show. Performances of Angus McGonagle the Argoyle Gargoyle (who “gargled Gershwin”) were about as well received as the real McGonagall’s public recitals, which often closed in a storm of rotten veggies. “The Tay Bridge Disaster,” McGonagall’s most famous poem, opens with these immortal lines:

Beautiful Railway Bridge of the Silv’ry Tay!

Alas! I am very sorry to say

That ninety lives have been taken away

On the last Sabbath day of 1879,

Which will be remembered for a very long time.

Equally winning, in my opinion, is McGonagall’s poem commemorating the premature demise of Queen Victoria’s fourth son, “The Death of Prince Leopold.” A particularly moving stanza reads:

Oh! noble-hearted Leopold, most beautiful to see,

Who was wont to fill your audience’s hearts with glee,

With your charming songs, and lectures against strong drink:

Britain had nothing else to fear, as far as you could think.

Not all connoisseurs of bad poetry appreciate McGonagall. Wyndham Lewis and Charles Lee, in their introduction to The Stuffed Owl: An Anthology of Bad Verse (1930), distinguish between “bad Bad Verse and good Bad Verse.” McGonagall they exclude as too clearly a producer of the former. The better bad stuff may be the off-day work of poets positively gifted. It may be grammatical and keep its meter. It is typically marked, however, by such qualities as bathos, sentimentality, and unintended humor.

So in The Stuffed Owl we are not surprised to find Wordsworth (“Spade! with which Wilkinson hath tilled his lands”), Henry Vaughan (“How brave a prospect is a bright backside!”), Tennyson (“He suddenly dropt dead of heart-disease”), Leigh Hunt (“Not without virtues was the prince. Who is?”), and Browning (“Irks care the crop-full bird? Frets doubt the maw-crammed beast?”). But the work of less familiar names is no less delightful. Christopher Smart (1722-1771), for example, spent years in Bedlam and was devoted to drink and prayer without ceasing but in Book II of his long poem “The Hop-Garden” he offers this bit of sound advice:

When in the bag thy hops the rustic treads,

Let him wear heelless sandals; nor presume

Their fragrancy barefooted to defile…

Meanwhile, John Dyer (1700-1758), whose magnum opus, “The Fleece,” was heartily denounced by Dr Johnson, gives us the following iambs on lambs:

Wild rove the flocks, no burdening fleece they bear,

In fervid climes: Nature gives naught in vain.

Carmenian wool on the broad tail alone

Resplendent swells, enormous in its growth:

As the sleek ram from green to green removes,

On aiding wheels his heavy pride he draws,

And glad resigns it to the hatter’s use.

Another poet with a gift for untrod subject matter was Samuel Carter, who published a volume of verse titled Midnight Effusions in 1848. In a poem titled “London” he praises the metropolitan sewer system:

Magnificent, too, is the system of drains,

Exceeding the far-spoken wonders of old:

So lengthen’d and vast in its branches and chains,

That labyrinths pass like a tale that is told:

The sewers gigantic, like multiplied veins,

Beneath the whole city their windings unfold…

Though not included in The Stuffed Owl, it turns out that Frederic the Great of Prussia – “Der Alte Fritz,” his soldiers called him – was a backward student of the muse as well. In Francis Parkman’s Montcalm and Wolfe (a history of the Seven Year’s War), we learn that “surrounded by enemies, in the jaws of destruction, hoping for little but to die in battle, this strange hero solaced himself with an exhaustless effusion of bad verse.” I’ve looked in vain for some of Old Fritz’s stuff in English translation but all I could find was a scrap of erotica (“Everything that speaks to eyes and touches hearts / Was found in the fond object that inflamed his parts”).

But I like this notion, in Parkman’s quote, of turning to bad poetry for solace at one’s failure to die in battle. It contains, I perceive, an accusation against our own weakling age, and a likely explanation for the decay of bad verse. Unfortunately, you see, no one nurses the ambition to die in battle anymore. Hence no one finds himself in need of solace on discovering at the end of the day that he has, yet again, failed to do so. And hence it also follows – o tempora! o mores! – that no one really gives it the old college try when it comes to writing bad poetry.

Most of us lack the ability to wrap the world in war “in order to rob a neighbor whom [we] had sworn to protect.” I suppose Frederick thought death on the battlefield preferable to a life of exile such as Charles Stuart’s or old age on a rock like Napoleon’s.

Samuel Johnson was hard on Frederick the Great’s style, calling it an imitation of Voltaire’s style such as Voltaire’s valet might have managed. Voltaire differed from Johnson in pretty nearly any opinion one can name, but thought this well said.

I am enabled to quote you some Frederick at third hand, for it has passed from Kant’s Critique of Judgment through John Crowe Ransom’s essay “Observations on the Understanding of Poetry”: Ransom remarks that Kant translated it into German, a language the king disliked, but that the translator of Kant gave it in the original French. The poem (asking your indulgence for my inability to remember how to type accented characters) is “sur les vaine terrerurs de la mort, et sur ley frayeurs d’une autre vie”:

Oui, finnison san trouble et mouron sans regrets;

En laisson l’ univers comble’ de nos bienfait;

Ansi l’astre de jour aut bout de sa carri`ere,

Repand sur l’horizon une douce lumi`ere;

Et les dernier rayons q’il darde dans les airs,

Sont les derniers soupirs qu’il donne `a l’univers.

f

I am no critic of French poetry, and Johnson and Voltaire aren’t here to consult.

There are notable poets of the last century who committed lines worthy of an anthology of the awful.

Ah, thank you for that, George, though it’s too bad I can’t read French.

I’ve dabbled on McGonagall myself, this is my favourite verse:

Then as for Leith Fort, it was erected in 1779, which is really grand,

And which is now the artillery headquarters in Bonnie Scotland;

And as for the Docks, they are magnificent to see,

They comprise five docks, two piers, 1,141 yards long respectively. –

McGonagall has apparently been translated into a dozen or so languages, including Mandarin and Thai — a supreme test for the translator you’d think, to bring any stanza of McG into another language without inadvertently improving it beyond recognition. (As they say, poetry is that which gets lost in translation …)

One thing the bad poets of the 19th century all seem to share is a fixation with the latest steam-age technology: trains, drains, docks, and bridges. This is a point made by Stephen Robins, editor of The World’s Worst Poetry: An Anthology, who quotes an extract from ‘Railroad Song’ by Thomas Holley Chivers (a failed inventor as well as poet):

Clatta, clatta, clatta, clatter,

Like the devil beating batter

Down below in iron platter —

Which subsides into a clanky,

And a clinky, and a clanky

And a clinky, clanky, clanky,

And a clanky, clinky, clanky;

And the song that now I offer

For Apollo’s Golden Coffer —

With the friendship that I proffer —

Is for Riding on a Rail.

Of this Robins comments memorably if a little mysteriously: “One can imagine him [Chivers] chanting the poem whilst leaping around and hiding behind pieces of furniture”. Indeed one can; and once imagined, it’s quite hard to unimagine.

brilliant!!