In his late fifties the great novelist and lecturer John Cowper Powys moved with his companion to a rural cottage in New England. As Jonathan Law reveals in this remarkable essay, the remote setting enabled Powys to give full vent to his bewildering range of manias and eccentricities…

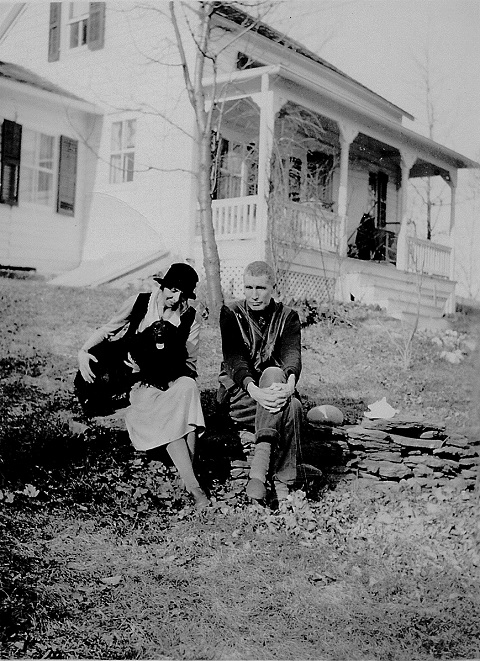

In the spring of 1930 John Cowper Powys and his companion Phyllis Playter moved into a “clean tidy oldish little Dutch New England cottage” in a remote part of upstate New York. At the age of 58 and after some 25 years of crisscrossing the States with his inspirational, barnstorming lectures on literature and philosophy, Powys was finally ready to give up his itinerant life and “to make the grand plunge … and try to earn my living by my pen.” Surely, in this rural quietude he would find “space wherein to expand” and to embark on the great literary works he had long contemplated.

Hillsdale, Columbia County must have seemed an ideal setting for the “semi-anchorite life” that Powys now planned. For all its “deep deep deep beautiful lonely wildness”, it offered a very human landscape of “Grassy slopes, park-like reaches, winding rivers, pastoral valleys, old walls, old water-mills, old farmsteads, old bridges, old burying grounds …” To Powys, the “Holland Dutch” architecture of the little, scattered villages breathed an atmosphere of “old world romance”, while the steep, wooded hills and the tiny valleys brimming with ferns and mosses woke a fierce nostalgia for his childhood in Somerset and Dorset. Above the farms and hamlets there were bare upland fields, separated by dry-stone walls and tall hedges of chokeberry, shadblow, and white-flowering thorn. But any sense of bleakness was dispelled by the “warm, hazy, vaporous, lovely grey waves of tender spring-like mists” that would sweep up the valleys and bathe everything in a liquid haze.

On his first day at the cottage Powys took an exploratory stroll through his new kingdom and set about “christening”, as he put it, “every stump and stone, every rock, swamp and rivulet in this virginal Arcadia”. Struck by a curious local name, he decided that the tall hill immediately behind their home was Mount Phudd, making the house itself Phudd Bottom. At the top of the hill there were some odd heaps of boulders and these Powys took to be Indian graves: henceforth the path between the stones became the “Avenue of the Dead”, while a solitary boulder further down became the “Altar of the God of Phudd”. In the months to come this supposed graveyard with its ghosts and its angry god would cast a dark shadow on Powys’s ever-delicate psyche (not to mention his bowels); but for the present he was quite exceptionally happy. Here, in this landscape at once foreign and familiar, mundane and mysterious, he could at last give himself up to what he considered “the most thrilling of all sensations, the sensation of sharing the little, evasive, casual waftures of mystic happiness, coming on the air in a doorway, on the sun-rays in an old barn, on the moon over a turnip-field, on the wind across a bed of nettles, and of sharing these with the forgotten generations of the dead.”

****

As summer gave way to autumn it must have become clear that life at Phudd Bottom would be no unmitigated idyll. The cottage was damp and rat infested and there was no indoor plumbing; when the New York winter bit, the only sources of heat were some primitive oil stoves and open fires that it was a constant struggle to keep alight. This might not have mattered so much if Powys had been blessed with an ordinary modicum of practical skills. However, his clumsiness was such that even the simplest of domestic tasks seemed beyond him. “Carrying out ashes he could usually manage, but lighting a fire could take him up to two hours,” comments his biographer Morine Krissdottir, “and he never did master the art of opening a window or pulling up a blind.” His laborious attempts to manoeuvre a tea tray were likened by one observer to the docking of the Queen Mary, while the thought of cooking breakfast could reduce him to despair at the complex logistics involved: “I can see my grand difficulty would be to get the fried egg out of its pan and onto the plate!” Indeed, Powys’s clumsiness was so extreme that a modern reader is tempted to diagnose some sort of dyspraxia syndrome; on one occasion he would end up with his arm in a sling after an ill-advised attempt to clap his hands.

Powys himself was well aware of “this mysterious anti-mechanic magic in my hands” but, infuriatingly, seems to have regarded it with pride; his curious home-made religion included as one of its elements an almost gnostic hatred of matter. All this meant that the burden of cooking, cleaning, shopping, and generally looking after John Cowper fell heavily on Phyllis, who was herself physically frail (“like a little huddled wren”) and suffered from gruesome periods that would confine her to bed for days at a time. After one such interlude, she came round to find that Powys’s attempts to light a fire had left black holes in the carpet and a thick layer of ash over everything: “An insane fury gripped me that he could be so absolutely without will or logic in relation to matter. I felt almost choked with the consciousness of it – and seized his hair … and made his spectacles fall off – and felt appalled at my conduct to the deepest nethermost fathom within me …” John Cowper formed the sound plan of appointing a housekeeper – but rather less wisely gave the job to a cousin of his named Warwick, who appears to have been eccentric even by the formidable standards of the Powys clan. Warwick was sent $300 – a good part of Powys’s yearly income – to make the journey from New Mexico; unfortunately, his regime proved so alarming that Phyllis fled the cottage to stay with family and Powys took to hiding in the garden. Eventually, he was forced to conclude that Warwick was “really rather queer in the head” and sent him packing; Phyllis returned and things resumed their wonted course.

***

If Powys took little part in the practical side of running the household, it would be wrong to suppose that he was idle. Indeed, his diaries – and the great Autobiography that he began at Phudd Bottom – show that he subjected himself to a daily routine that most people would find exacting.

Although he hated early mornings, Powys rose at dawn to commence the long series of obsessive-compulsive rituals that gave shape to his day. First, he would lay his fingers on a “little sacred talisman” from the tomb of St Therese, and say a prayer for his brother Llewelyn, a devout hater of all religions. There would follow a long series of prayers for his neighbours, including those in the Moravian burying ground just outside his window. As a climax, Powys would plunge his head into his washing basin and hold it there while he prayed for his dead grandfather “for it has entertained me from my childhood to see how long I can hold my head under water”. Although fervent enough, these prayers were hardly the most orthodox; as a child, Powys had loved to suppose that he was a great magician with the power to command angels and spirits and this idea would remain at the core of his self-image. In his particular kind of prayer, he would explain, “I act the Trinity … for I project my waves of magnetic force from the three centres of my being; from my brain, from the pit of my stomach, and from the centre of my erotic energy. I won’t weary you with a detailed description of the armies of magnetically created spirits that I thus send forth ….” He is, however, willing to divulge that he thinks of his spirits as “variously coloured”, enabling him to send differently tinted spooks on different types of errand.

All this achieved to his satisfaction, Powys would walk in the woods and feed the skunks from a garbage pail while continuing to send his colour-coded spirits to anyone who might need their help (an operation accompanied by various “spasmodic motions” of his body). With his druidical oak cudgel in his hand, he would then visit a “great mossy natural knoll” that he had named Merlin’s Grave and invoke the great magician while burying his face in its damp rubble. His ritual circuit always involved halts at two very important trees. At the first, an old apple tree that he named Polutlas, the much-enduring, Powys would again pray for his grandfather. At the second, an “enormous and very ancient willow”, he would indulge in a more personal type of therapy:

To this aged tree I have given the mystic name of the “Saviour-Tree”, and here and now I recommend to all harassed and worried people who can find in their neighbourhood such a tree—and it needn’t necessarily be a willow—to use it as I do this one. For the peculiarity of this tree is that you can transfer by a touch to its earth-bound trunk all your most neurotic troubles! These troubles of yours the tree accepts, and absorbs them into its own magnetic life; so that henceforth they lose their devilish powers of tormenting you.

Powys certainly had more use for such a tree than most. A complete list of his “frantic and misery-causing manias” would fill pages but the thoughts that agonised him most sprang from certain erotic books to which he had been addicted in his youth. These were French by origin, violently sadistic by nature, and in his own words “transported me beyond all other feelings I have known”. Although he was now strict in forbidding himself even the mildest sadistic thought, sometimes a “demon-image” from one of these terrible books would rush at him “like a frantic harpy”, a “wicked ripple” would float through his nerves, and all at once the pulses in his wrists would begin “to tick, as if I were wearing two wrist-watches”. Powys would atone for such lapses by adding various penitential acts to his routine; in particular, he would spend hours at the stream with a little net, carefully ‘rescuing’ fish by moving them out of shallow water: “This matter of saving fish in my small river was constantly on my conscience … and I used sometimes to walk as far as a mile carrying a pail of them, till I found an adequate pool for their reception.” There were also flies and bluebottles to be rescued, prayers to be made to Demeter and Cybele for all the down-and-outs of London and New York, and – if ever he found the time and the health and the peace of mind – books to be written…

***

From the winter of 1931-32 a new set of manias came to rule Powys’s life as his mind dwelt ever more darkly on the supposed “Indian graveyard” behind his cottage. Although he would sometimes admit that his knowledge of Native American culture came mostly from Hiawatha, Powys became convinced that the rocks on Mount Phudd were the burial mounds of Mohawk chiefs, angry ghosts who demanded some kind of ritual obeisance. Accordingly, “at the two equinoxes and at other pivotal days” Powys would climb to the wooded summit of Phudd “and walk up and down this “death-avenue”, as I liked to call it, kneeling in front of each pile of stones and invoking these dead Indians.” More onerously, the Indians began to call him each day to the Altar of Phudd, where he was ordered to go through a complex rite of tapping his head on this grey, lichenous boulder. Eventually even Powys – who had a self-confessed “mania for ‘bowing and scraping’ to idols” – began to feel that the ghosts were making unfair demands on his time and comfort. A series of journal entries show how he struggled to assert his self-respect:

I heard the Indian Tombs on top of Phudd telling me this layer or film of ice lay on them & begging me to climb up the Mount & salute them. This I was too lazy to do. I notice how if you are to be happy in this world you have forever to be hardening your heart …

I prayed to the dead Indians in the highest heap of stones and also in the first I came to and also in two heaps in the Avenue of the Dead up there. But as I went away three more ghosts of dead Indians—dark swaying slender bodies cried come to me—come to us! come to us! But I would not …

I visited my old favourite dead tree—O I did enjoy it so. But I was nervously agitated by those Ghosts of Indians calling to me & I talked to the tree saying unto it “Self first—self first—self first—Dead Indians second!” but the tree answered me not a word.

When Powys became openly rebellious, the Indians chose to exert their power through some very below-the-belt tactics. For many years John Cowper had suffered from hideous gastric troubles, almost certainly made worse by his freakish diet (by this stage he consumed almost nothing except bread, tea, and raw eggs). As a result he had become dependent on regular self-administered enemas; “For two or three years I have not had one single natural action of the bowels” he confided in the Autobiography, adding that he had come “greatly to prefer this artificial method to the natural one!” Unluckily, this gave Powys’s spectral opponents the chance to strike back in a particularly intimate way:

The Indians of the Hill & the God of Phudd commanded me to come to the Phudd Stone & tap my head. But I refused. I too am a Magician! I said. So they set themselves to show their Power & I set myself to show my Power … I gave myself a good Enema after my fashion with the squeezing tube and I squeezed it sixty times. The spirits of the Indians were making a grand coup, a great rally against me however and all went wrong. It would not work!!

Indeed it would not. Powys remained in an agony of constipation for some days before realising there was only one solution; to her myriad other chores, Phyllis must add the administration of the twice-weekly enema.

***

And so the months passed, and so the years. March would bring the phoebe bird, the hermit thrush, and the first woodchuck in the meadow; April the red maple flowers, white bloodroots, delicate hepaticas, and little green frogs by the stream. May the water mint and the white-flowering shadblow. Powys went on chanting his prayers, tapping his head on stones, and climbing Phudd Hill to watch the sun go down “like a great purple plum that you couldn’t eat”. In his four years at Phudd he would complete two of his greatest novels – A Glastonbury Romance and Weymouth Sands – and write most of his wonderful Autobiography. Looking back he would recall this time as one of extraordinary happiness and fulfilment: “years in which I had a greater chance to realise my identity than I have ever had in my life”.

Hilariously mad to the extent of making me laugh out loud. I felt a bit guilty finding such madness amusing and was relieved to learn that he recollected the period as a happy one.

I particularly enjoyed the account of fish rescuing.

Yes, fish rescuing was my favourite one as well.

That whole ‘I have no concept of matter’ thing must have absolute hell to live with (so that even his soul mate and surely the only person in the world who could tolerate him is gripped by an ‘insane fury’). It reminds me of the awful Skimpole in ‘Bleak House’ and his claims to have no idea about money.

Beautifully written piece. How can anyone not love this man? I’ve loved JCP for many years and have read about his crazy quirks before, all of which make him more endearing. But they still surprise and amaze; your account is very forgiving and affectionate. One of my favorite memories is of reading the Autobiography, slowly, over months, in the early morning, sitting in my car parked near the Long Island Sound in a secluded waterfront park. In perfect solitary woodland waterfront summer silence. Last year I managed to locate a short, rare video of JCP speaking – I have a copy – and regret only that I was never able to see him live; nor did I even know he existed when it would have been possible. It’s always wonderful to know there are other JCP lovers out there. If I lived in England I’m sure I’d meet up with them (I know there’s a society that has, or had, annual conferences/gatherings.)

How can anyone not love this man?

Perhaps we should ask Phyllis.

This is hilarious and worthy of a sequel to Paul Johnson’s Intellectuals. Johnson traced the gruesome trail of betrayed women and abandoned children left behind by soi-disant sages who earned their livings preaching how we should all live. What would he make of those who pronounced on the great political and social issues of the day, but couldn’t open a window or get a fried egg out of a pan?