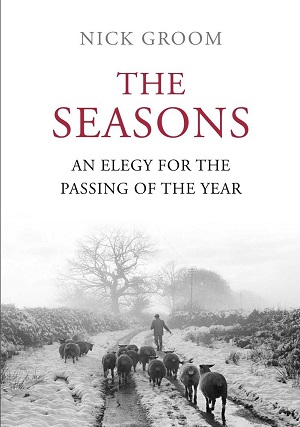

Professor Nick Groom’s new book The Seasons: An Elegy for the Passing of the Year is a celebration of the English seasons and the trove of strange folklore and often stranger fact they have accumulated over the centuries. In an exclusive post for The Dabbler, Nick looks at the English Christmas…

Hallowe’en, with its black plastic witch costumes and gruesome sweets, is over. Pumpkins can now be bought for a pittance. For my daughters and their friends (and for shops and supermarkets up and down the country) that means one thing: Christmas. But England once had a far richer tapestry of seasonal festivals, which patterned and punctuated the year. Who now delays gathering nuts until after Holy Cross Day? Who eats a goose at Michaelmas? Little remains of this calendar of saints days, weather lore, and local customs; instead, this harvest-home of traditions has been replaced by a dumbed-down agenda for the year based on a handful of annual retail events: Christmas, Easter, Hallowe’en, and Valentine’s Day (although commemoration of the maverick Gunpowder Treason Day has remained fairly immune to exploitation). But it is not too late to rediscover those lost festivals that once connected us organically to the year, from the first snows of winter to the last gleanings of apples and pears.

We are of course a profoundly more urban and a less rural population than ever before, increasingly cut off from the land and its produce, and so the shared heritage of the yearly cycle has accordingly become ever more remote from its agricultural origins. Instead, our experience of the year reflects contemporary society, which in its technological and agricultural sophistication will go to the ends of the earth to source or grow asparagus in the autumn, strawberries in the winter, and apples all the year round. Our awareness of the passing of the year is now prompted more by seasonal ‘limited edition’ flavours of gourmet potato crisps than by birdsong and wild flowers.

The consequence of this is an impending cultural catastrophe because our collective memory of the year is heading towards extinction: what was once a cornerstone of national identity, braiding together remembrance, history, and landscape, is increasingly derelict and forgotten. Only tattered remnants survive. What will have been lost to us when we no longer recognize, or even hear, the cuckoo call in the springtime, when we read the nature writing of Gilbert White and John Clare not for the shared pleasure of the shifting seasons but as an archaeological relic of a bygone era?

Reconnecting with our seasonal heritage is one of the best ways of reawakening what it is to be English. So let the Scots keep their Hallowe’en in its re-imported, American form – the sombre English festival for that time of the year is Hollantide, which has its own wealth of folklore. And by acknowledging Hollantide, a distinctive little piece of the cultural jigsaw is restored. How many students have wondered why Shakespeare’s Prince Hal remarks of Falstaff, ‘Farewell, the latter spring; farewell, All-hallown summer’? Shakespeare was not writing metaphorically, but from his direct experience of the seasons. We’ve just had an ‘All-hallown summer’: warm days during Hollantide at the beginning of November; a belated frolic.

So to Christmas: the biggest seasonal festival in England, one that has in fact become characteristic of England. Christmas affords an opportunity to identify and celebrate typical English values and culture. Giving provisions or doles to the poor and needy was customary on St Thomas’s Day (21 December) to ensure that everyone enjoyed a good holiday, and meals during these celebrations inverted social status in order to support the poor and needy. Presiding over this world turned upside down were boys elevated to the status of bishops, and the ‘Lord of Misrule’ [above] a carnivalesque figure bedecked with holly – ‘Sir Christmas’, or ‘Old Father Christmas’. Natural order was also overturned alongside social order: on Christmas Eve decorated boughs and greenery were brought into houses – holly, ivy, and mistletoe.

Christmas dinner was for many years the roast beef of old England; turkey was first imported in the sixteenth century and by the eighteenth was considered traditional; goose was for the poor, who dined on the birds left over from Michaelmas. Mince pies, made of spiced meat, were oblong and known as ‘coffins’ but eating them was lucky for the forthcoming year: ‘As many mince pies as you taste at Christmas, so many happy months will you have’. Christmas cake was usually reserved for Twelfth Night – a wise reminder to stretch celebrations into the cold, dark days of the New Year.

Old Christmas was therefore a time of questioning hierarchies and sharing with the lower social classes. In the nineteenth century, the tradition of decorated boughs was overtaken by Christmas trees, and the American ‘Santa Claus’ replaced Old Father Christmas. The first Christmas card was sent in the same year that Dickens’s novel A Christmas Carol was published, and the first Christmas crackers were developed by confectioners competing to make their bon-bons more appealing. But the Victorians also assiduously maintained donations, alms, and charity boxes, their enthusiasm for Christmas being inspired by guilt at the condition of the labouring classes. It was a reminder of poverty, a communal reparation for the years of Enclosure Acts, urbanization, and industrialization that had provided the grimy foundations for the workshop of the world.

Today, we would do well to add to our Christmas celebrations some of these traditional associations and customs. But reconnecting with the seasonal calendar doesn’t just have to mean reviving old traditions: every custom has had its beginning. I am fortunate to live in a village where we traditionally wassail orchards every January – at least we have done for the past two or three years since establishing a community cider press. So perhaps we should make Christmas in the twenty-first century an annual reminder of our disappearing seasonal environment: of holly, ivy, and mistletoe; of robins and wrens; and of trees. So, plant a tree on Christmas Day or simply feed our native birds before you enjoy the fruits of the season. Make it your own tradition.

Looks like a good book, Nick. Funny how most cooking and travel shows emphasise the european seasons and festivals in a way that is incredibly attractive to middle class brits, yet we mostly ignore our own rich history of such things.

It was great when I lived in Bavaria and the year was marked out by festival days when everyone would get together to celebrate the new season’s beer. The UK’s horrendous seasonal shopping festivals are pretty shabby in comparison

Dear Worm

Your are quite right – so much of what the middle-classes find so charming when they holiday abroad is already happening on their doorsteps. And yes, the English seasons tend to dissolve into marketing campaigns. But there are ways of turning this around: local breweries could, for example, make St Nicholas’s Day (6 Dec) the day on which they introduce their Christmas ales (those dark, malty brews that are so tempting on winter nights). St Nicholas was certainly celebrated in some parts of England, but more significantly it would distinguish the American ‘Santa Claus’ from the Old English Father Christmas – who of course I much prefer: a mischievous lord of misrule and a king of carnival, rather than some commercial icon. The English Christmas is one of games and play, not consumerism. And the tradition does continue, if now predominantly as a Radio 4 programme throughout the year: I’m Sorry I Haven’t A Clue. Every one of those games that Humph and now jackdee comperes has the spirit of Old English Christmastide. And it is how I will celebrate the season.

The subject of England and, particularly, if not exclusively, its history, always arouses my interest, and this superb post excited that interest to the extent that I immediately ordered a copy of The Seasons: An Elegy. One of my favourite books is Steve Roud’s The English Year in which he presents a month-by-month guide to England’s customs and festivals. In the section on Christmas he refers to Robert Southey’s certainty, expressed in 1807: ‘All persons say how differently this season was observed in their fathers’ days, and speak of old ceremonies and old festivities as things which are obsolete. The cause is obvious. In large towns the population is continually shifting; a new settler neither continues the customs of his own province in a place where they would be strange, nor adopts those which he finds, because they are strange to him, and thus all local differences are wearing out.’ Roud asserts that this was the beginning of what could be termed the ‘new seasonal nostalgia’, when everyone agreed that Christmas was not what it was and that something should be done about it. Roud adds that over the following decades, something was indeed done as, in modern terms, the season was rebranded and relaunched. So, perhaps hope remains. I particularly liked that final paragraph in your post, Nick, and am now wondering what I can do to make a difference, even if that difference will be minute in the scale of things. I feed our native birds daily throughout the year, so perhaps a little wassailing is on the cards. Hold on a minute while I ask the missus if she fancies a bit of wassailing……

The Cotswold village of Bibury holds duck races on Boxing Day – variations on plastic ducks being raced down the river with numbered competitors drawn by lot for a couple of quid – with all proceeds going to the local football club. It’s hugely popular, attracting large crowds who revel in mulled wine and mince pies.

This is a new tradition, which sounds very much in the spirit of old Christmas. So, as John remarks, no need to lose hope. In fact, there looks to be a huge opportunity in Michaelmas for farmers of geese, if only they could get some celebrity sponsorship. Someone should tell Waitrose.

And to think I stayed home on Boxing Day when I could have been down in Bibury: mulled wine, mince pies and plastic duck racing on the river. I’d not thought of the existence of Bibury for several years, but was nudged awake by your comment, GAW. It immediately brought back memories of what was a rather special place. I particularly remember a magical few hours at Arlington Mill, where our two daughters watched enthralled by the antics of water voles:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/16398310@N08/11622635686/

Apologies for this bout of self-indulgence, which will have little or no interest for readers – but it transports me back to a lovely holiday in the Cotswolds).

Christmas 2014: “Are you and mum coming to us on Boxing Day?” “Not a chance; we’ve entered our plastic duck in the race down the river at Bibury.”