All readers are familiar with the distinctive branding of Penguin paperbacks, and there can be few Dabblers who don’t have at least half a dozen or so on their bookshelves. Karyn Reeves, however, has about 2,000 of them – and she reviews them on a weekly basis on her blog A Penguin a Week. Here’s why…

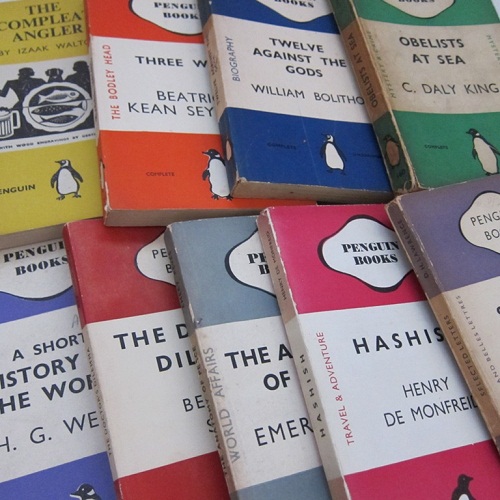

The iconic branding of Penguin’s early paperbacks is so recognisable that I can only recall one occasion when someone looking at my bookshelves asked what they were and why so many of them were orange. I have thousands of old Penguins and Pelicans, but I concentrate my collecting these days, and my reading, on Penguin’s main series – the series of books which began with Ariel in 1935 and which were numbered approximately in publishing order, with their numbers displayed on the spine. These are the books which feature Penguin’s classic branding, and perhaps for that reason I often see and hear them mistakenly referred to as Penguin Classics. But Penguin Classics are a completely different series of books which never carried the tripartite branding, and which are all still available; they recently (and controversially) added Morrissey’s autobiography to their list.

Penguin’s main series was far more eclectic. Its focus was always contemporary fiction, but over time its list expanded to include books of plays, essays on world affairs, several volumes of crossword puzzles, and even surveys of research. And the early Penguins came in a far greater range of colours than the well-known orange and green; there were also red, cerise, light-blue, dark-blue, purple, grey and yellow Penguins. Throughout the years, as they moved away from the simple tripartite coloured branding of the early years and introduced illustrated covers, they always remained innovative in exploiting new technologies and maintained their focus on design and quality. By the time Penguin Book founder Allen Lane died in 1970 there were approximately 3,000 titles in the main series, most of which I understand to be no longer available, and many of which seem largely forgotten. I have about 2,000 of these titles, and I am still searching for the other 1,000.

Penguin’s story is said to begin with Allen Lane, managing director of The Bodley Head, on the platform at Exeter St Davids train station. He was returning to London after a visit to Agatha Christie and her husband Max Mallowan, and he was facing a bookless journey as he could find nothing of interest at a station bookstall which sold only popular magazines, reprints of Victorian novels, and thrillers of doubtful quality. It gave him the idea that here was a market waiting to be tapped, and that by leveraging print runs in the thousands he could make contemporary, appealing and high quality paper-bound reprints of contemporary fiction available through retailers other than bookshops. They would need to be inexpensive to sell in sufficient quantities, and he fixed on the idea of books priced at a sixpence, the cost at the time of a packet of ten cigarettes. When the board of The Bodley Head refused to support a move into paperback publishing, Allen Lane set up his own company and forged ahead with the assistance of his brothers Richard and John.

And so Penguin Books began in July 1935 as a series of ten dust-jacketed sixpenny paperbacks. The initial ten titles, which included works by Andre Maurois, Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers and Ernest Hemingway, had been chosen partly for their literary merit and partly because they could be secured, as few publishing houses were willing to support the new venture by making their titles available. The early attempt at branding is one of the novel features of the earliest Penguin paperbacks: they possessed simple but striking covers and spines colour-coded for genre, so that six of the initial ten had orange covers indicating fiction, two were green to denote crime, and two were dark blue indicating biography. The early difficulties securing sufficient orders meant that the fledgling venture was a precarious one, and that Penguin Books could have folded before it began.

The idea of publishing fiction in paperback form was not a new one. Cheap paper-bound reprints featuring lurid covers, tiny print and poor-quality paper had been available for many years, and it meant that mass-market paperbacks carried connotations of low quality in both content and style. An exception to this was the Albatross Modern Continental Library which was producing inexpensive paper-bound English-language reprints with modern styling even before Penguin was launched, but these were only available on the continent, and the Albatross Library didn’t survive the Second World War. Lane adopted many of the Albatross Library’s innovations, including the dimensions, the colour-coding for genre, the modern geometric styling, and even the idea of a bird-inspired logo. But Penguin’s approach to paperback-publishing also differed from their competitors in that they embraced the idea of breadth – they focused on literary merit rather than best sellers, allowing successful titles to cross-subsidise those which were less popular. And they were innovative, establishing successful series such as Penguin Classics, Pelicans and Puffins, and pursuing novel forms of marketing such as the Forces Book Club and Puffin Young Readers.

The year after Penguin’s launch, George Orwell wrote ‘In my capacity as reader I applaud the Penguin Books; in my capacity as writer I pronounce them anathema.’ But George Orwell was wrong: Penguin Books actually offered a new market to authors whose sales had begun to dwindle, and with print runs in the thousands, a Penguin reprint meant an opportunity to rejuvenate flagging sales and to be exposed to a new audience. Allen Lane had glimpsed the future, and in this decade when several publishers suffered financial difficulties, including The Bodley Head, he had foreseen that the answer could lie in expanding the readership. Cheaper books could turn book-borrowers into book-buyers and recruit new readers by competing with other inexpensive forms of entertainment.

I knew nothing of this history when I fell into collecting them. In the early 1980s, vintage Penguins were cheap and abundant, and I soon realised that they were also reliable – you could buy an orange-spined book at random and almost always find it worth reading, and so I started scanning the shelves of second hand bookshops looking for those recognisable spines. All these years later it still seems to me a very reliable way to choose something to read, and I can only think of a handful of titles which have proved disappointing. Sampling Penguin’s early list has provided the opportunity to discover forgotten authors and forgotten works, and to be introduced to authors and books I would never have come across otherwise. And it offers a way to access information about the past which is uncontaminated by later biases and preconceptions or by what someone else considers important enough to remember. It is the incidental details in the stories, the references to everyday life, which often surprise and interest me the most.

I think that there is much to be said for holding onto the past, and at least trying to take a temporary stand against the inexorable process by which things gradually slip into obscurity. These days I read one of these pre-1970 Penguins each week and then write a few paragraphs describing it for my blog A Penguin a Week, partly as my own record of my reading, but also to make a record on the internet of something which was once created, and to promote the idea that some of these forgotten books are worth rediscovering. I hope in time to both find and read them all.

Whenever someone makes a sneering comment about bloggers and blogging, I point them in the direction of ‘A Penguin a Week’. It’s a wonderful project that could only exist in the age of the internet and Karyn Reeves is building an archive that is of inestimable value.

In the wrong hands, ‘A Penguin a Week’ could be a bonkers idea, but Reeves approaches each book with an open mind, whether it’s a meditation on the meaning of existence, or a third-rate, long-forgotten crime novel from the 1940s and writes incisive, balanced reviews. The quality of the criticism is the thing that makes this project work as much as the initial idea.

The prospect of having to read a randomly-selected pre-1970 Penguin novel every week would horrify most people. Anyone who cares about books should salute Karyn Reeves for undertaking this extraordinary venture and discovering a few neglected gems along the way.

A book a week is good going! Very interesting and noble undertaking Karyn, I salute you (and have subscribed immediately)

Has anyone tried to tackle a Pelican book a week? That would be tough

A great project indeed – and Penguin was a great publishing venture – but surely the oldest Penguins are now falling apart, aren’t they? I rarely come across one in readable condition…

One of my favourite British bookshops is The Topsham Bookshop in Devon, which organises its fiction according to its publisher. It is fascinating to see all the different styles.

Didn’t Foyles used to do something like that? Although ‘organise’ is probably flattering their system of chucking everything in big piles on the floor.

The Trover Shop in Washingtton, DC,did that. I don’t remember the visual effect particularly, rather the frustration of trying to find the book one was looking for. (Quick, name the American publishers for any of J.F. Powers, Saul Bellow, Louis Auchincloss, Martin or Kingsley Amis.). I suppose that it simplified their inventory work.

At the time of launching his imprint, and for some time afterwards, Allen Lane had to confront many doubters who couldn’t see the future as clearly as he could. It took some publishers quite a while to realise that what he was doing for good the business – his and theirs. One of the doubters was my friend and mentor Neil Webster, who knew Lane and was actually offered a partnership by him: Neil turned Lane down, on the grounds that the venture was too risky.

A Penguin A Week is an excellent blog, looking at often neglected or forgotten books and treating them seriously – something very much in keeping with what The Dabbler does, of course. Karyn Reeves’s other blog, Vintage Penguins, another admirable enterprise, holds up for inspection the covers and cover illustrations of early Penguins, reminding us how well designed and presented many of those paperbacks were.

As a long-time Penguin collector, I find Karyn’s website invaluable for advice on both content and cataloging. In my view, there are dozens of neglected gems among the first 1,000 Penguins. My personal favourites include Nos 145-46 – The Paradine Case (later filmed by Hitchcock), No. 674 – The Journal of a Disappointed Man and No.953 – Murder of my Aunt.