This week Mahlerman takes us on a journey into “a Teutonic soundworld to which few non-German singers posses a passport”…

In early 19th Century Germany, ownership of the universal domestic pianoforte expanded from Royalty and the landowning super-rich to embrace the new middle-classes; and in parallel with this expansion emerged just four major composers who produced over one thousand songs between them, to cater for this new socio-economic group. And what a strange quartet they make.

All of them were made of the right stuff but only one, Robert Schumann formalized his relationship with Clara Wieck, in 1840. Two others, Franz Schubert and Hugo Wolf (and probably Schumann also) contracted syphilis, which contributed to their early deaths. Both Wolf and Schumann attempted suicide by drowning, both asked to be admitted to an insane asylum, and both ended their days there. Only Johannes Brahms had anything like a ‘normal’ life, but he weaves himself back into the story care of his life-long love (almost certainly unconsummated) for Schumann’s wife Clara.

Johannes Brahms was born into a working class Lutheran family in Hamburg in May 1833, and he grew into a beautiful, shy, golden haired youth. Fame, and with it wealth, was a long time coming, and he was in his late thirties before the German Requiem made his name, releasing him from money worries. He enjoyed the fruits of his genius, eating and drinking expansively and adding the patriarchal beard that completes the more familiar picture we have of him. He wrote more than 200 songs and duets, most of them infused with the folk elements, the volkslieder, that he held so dear. To this framework he added the values of seriousness, respect and rectitude that was the still centre of life for the German bourgeoisie. His Opus 91 comprises two exquisite songs supported by viola (Brahms’ favourite instrument) and piano, played on this video by Daniel Barenboim and the sometime leader of the BPO Wolfram Christ, and sung by Jessye Norman; here the first of them, to words by Friedrich Ruckert, Gestillte Sehnsucht (Stilled Longing).

Brahms cared little for the poetry that was the wellspring, the ignition, that lit the poetic flame within Robert Schumann, one of the great musical car-crashes of the 19th Century. He possessed a lyrical imagination of the highest order, but the pure essence of his genius was rarely expressed on a large canvas – the symphonies, while containing some beautiful effects, usually fail through poor construction, and the sense that the composer has bitten off more than he can chew. Reduce the scale, shrink the ambition, and a formal simplicity, a poignant sentiment emerges that perhaps was not equalled even by Schubert. The Liederkreis cycle of twelve songs is a great example of Schumann’s genius for the small scale. Intensely romantic, they inhabit a Teutonic soundworld to which few non-German singers posses a passport. Here I have reproduced the marvellous poem by Eichendorff that forms an equal part of the fifth song Mondnacht (Moonlit Night), and it would be a stronger man than I who could remain unmoved by these magical reflections and their hidden meanings. And for good measure, I have included a reading in German by Dieter Mann which has its own music.

Es war, als hätt’ der Himmel

Die Erde still geküßt,

Daß sie im Blüten-Schimmer

Von ihm nun träumen müßt’.Die Luft ging durch die Felder,

Die Aehren wogten sacht,

Es rauschten leis die Wälder,

So sternklar war die Nacht.Und meine Seele spannte

Weit ihre Flügel aus,

Flog durch die stillen Lande,

Als flöge sie nach Haus.It was as though the heavens

Had silently kissed the earth,

Such that in the blossoms’ lustre

She was caught in dreams of themThe wind crossed through the fields,

And swayed the heads of grain

The forest softly rustled

How starry was the nightAnd my soul spread

Far its wings

And sailed o’er the hushed lands

As if gliding home.

Here is the German Lyric Bass-Baritone Matthias Goerne to sing the piece in a way that invites no comment. The pianist is Eric Schneider.

;

And then there was Hugo Wolf, another suicide in waiting. Born in the same year as Gustav Mahler, 1860, his short life just crept into the 20th Century. At age 28 he had written practically nothing – and then, in a kind of fever, he penned 53 Morike lieder, 51 Goethe lieder, 44 Spanish lieder, 17 Eichendorff lieder and a dozen by Keller plus a few individual pieces. Over 200 lieder in less than two years – then silence for two years during which time he suffered an almost complete mental collapse, there being no real cure for the syphilis he contracted in a brothel. In November of 1891 the muse returned, and he wrote 15 Italian lieder, sometimes several in one day. Then, a month later, the muse vanished – for five years. The second volume, completed in a month, appeared in 1896. He was 36 years old and had seven years to live. At the close of that year a friend sent him some of the poems of Michelangelo (yes, that one) translated into German, and he immediately composed melodies for the first three before madness returned. He never completed the cycle but, in a period of remission before his final visit to the asylum, he revised the Three Michelangelo Lieder, the second of which, Alles endet, was entstehet (All that is created, must perish) is sung here by the late, lamented Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau standing just to the side of Daniel Barenboim.

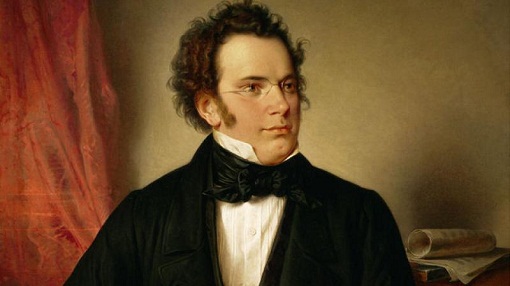

Im Abendrot (In The Evening Glow) D.799 by Franz Schubert. What to say, that hasn’t already been said. Probably written a couple of years before his death at the age of 31. Open the score and it looks nothing much. Get hold of Hans Hotter and Gerald Moore in 1957 (I did) and see what they can make of it. Get a hankie. Try and be strong. Fail.

Blimey MM you’ve really wheeled out the big guns today – a post to savour that’s for sure. Strauss’ Im abendrot has to be one of my all time favourite pieces of music so its great to discover another lovely piece with the same name

Wonderful stuff, though alas the fourth video has been blocked in my country “on copyright grounds” I shall track it down nonetheless…

Prior to reading your post, Mm, I could have written an exhaustive account of my knowledge of Lied on the back of a postage stamp using a 6” distemper brush and still have room for a photo of Schubert. Now, having read the post and revelled in the story and your use of language, if not all the music, my knowledge of Lied has skyrocketed.

I love the Brahms; the accompanying viola adds tremendously to the piece and I do wonder if I would have been equally moved by piano accompaniment alone. Well, of course I wouldn’t: that’s why the great composer included the instrument. And what a wonderful instrument it is and what an encouragement this is to revisit stuff I haven’t listened to for years, such as Britten’s Elegy For Unaccompanied Viola and Walton’s Viola Concerto. Thanks Mm.

It is a great pity that Schubert got his leg over once too often with the wrong type of girl and succumbed to the pox at 31. How selfish to deny us further fruits of his genius.

Forget the middle classes… is it a sign of the times that they’re closing the piano department at Harrods?

Although the answer to your question Susan is almost certainly ‘yes’, the quote from Harrods that ‘pianos don’t do as well as handbags’ speaks volumes. It is probably good news, as the few sales of pianos that are out there shift to companies that specialize, and can offer a decent service – and there are plenty of them.