Sarah Ogilvie’s new book on the Oxford English Dictionary, Words of the World, caused a stir recently when the mainstream media reported it as claiming that a former editor, Robert Burchfield, had deliberately purged it of foreign loanwords… Jonathon reads the book and sets the record straight…

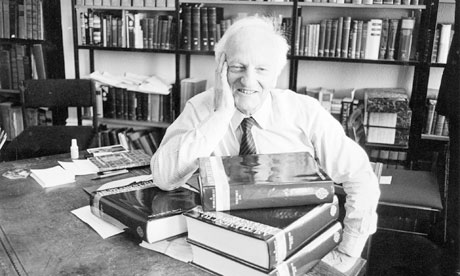

So my friend publishes her book. My friend being a linguist and lexicographer (although currently working as neither) this book is a pointilliste discussion of one aspect of dictionary-making: the decisions that were made by a succession of those editors who were responsible for the OED: James Murray for the first edition, OED1, William Craigie for the supplement of 1933 and Robert Burchfield [above] for the 1972-86 supplements, which, when absorbed into the original work, became 1989’s OED2. Professionals will recognise it as part of a trend: discussing, with extensive use of the OED’s own extensive records and the new possibilities of computer analysis, the way in which what is the English-speaking world’s greatest act of lexicography is made. In this it is of a part with Linda Mugglestone’s Lost for Words (2005) and Charlotte Brewer’s Treasure-house of the Language (2007), both of which focussed on certain aspects of the creative process. Because my friend is both highly intelligent and notably articulate, and because for some the making of dictionaries – notably what goes in and what does not, and of course why such judgements are made – is of importance, this is a fascinating book, and because she worked for a time at the OED, on foreign ‘imports’ into English, or more properly ‘loan-words’, she is able to provide an insider take on the story. But the fascination, I suggest, is likely to be restricted to those of us in and around ‘the craft’. I cannot, with the best will on offer, suggest that this study, with its wealth of detail, graphs and statistics, offers the lineaments of a potential best-seller.

I should like to suggest that the story is simple: it is not. Lexicography demands value-judgements and such judgements must be made by individuals. These individuals, try as they might, remain human and such humanity plays its part in influencing even the most disinterested. Beyond the individual lie pressures: social, cultural, chronological in the form of a publisher’s urgent deadline and perhaps most of all, economic, the need to recoup investment. The pure scholar would have no time limits and of course, being the record of an ever-expanding and changing language, no dictionary is ever ‘finished’. The pure scholar might have existed in the eras of ‘men of letters’ (who tended to be men with private incomes) but these are other days.

It is impossible to précis what my friend has done, but I shall try. If the book has a single aim it is to show, despite all the arguments then and now, that the OED was consistently open to as wide as possible variety of what is summed up as ‘English’. This sounds simple: it is not. Of the many tasks set itself by the what was originally the New English Dictionary was covering as far as possible the whole English language. But what, here, did English mean? Obviously the English of England (and the remainder of the UK). After that it was all questions: did one include the particular English of those countries – e.g. America, Australia – for whom it was the primary form of speech and writing – but which included terms were not those used ‘at home’. Did one extend one’s embrace further still, to those nations where local terms, for instance the kind of Raj vernacular that one finds in Hobson-Jobson, were regularly used by English speakers, and beyond that to the kind of localisms that cropped up in the tales of explorers and travellers, and which an English speaker was thus required to understand. One drops the pebble in the pond: just how far does one follow the ripples? This is gross over-simplification, but that such decisions lead to choice is undeniable and it is the choices – with their implications as to what, thus, exactly was ‘English’ – that my friend’s book illumines. Different editors, of course, had different takes. Murray had the problem of fighting off those ardent prescriptivists who believed in language that was ‘good’ or ‘pure’ and thus saw all else as ‘barbarous’ (in its root sense of ‘foreign’). Burchfield, a New Zealander, promoted himself and his new edition as the great, welcoming promoter of what was gradually becoming known as ‘world English’, and as such the antithesis of Murray who had allegedly represented an overly anglocentric, imperialistic world-view.

So my friend publishes her book. It is called Words of the World and her name is Sarah Ogilvie. I see it in the London Library, grab it, read it. And feel as I have laid out above. A few days later I see, am mailed in fact, a story from the Guardian . It features her book. It claims that Burchfield, far from embrace and expand the OED’s representation of world English, had almost purged it. Well, knocked out a substantial chunk what had been there in the 1933 Supplement. It puffs and blows. It sniffs, sensing that concept so rarely seen in dictionary-world: a scandal. It is picked up, as such things are, by the Internet. It is also, argue a number of experts, not to mention Dr Ogilvie herself, a misrepresentation.

The nature of scholarly books such as Words of the World is that they are not susceptible to speed-reading. Speed-reading, is, on the other hand, the stand-by of much literary journalism. Thus the promotion by each new dictionary of half a dozen ‘hot new words’ that will, it is hoped, grab some publicity. Dr Ogilvie does indeed put Dr Burchfield through the wringer, noting the sometimes yawning discrepancies between his claims – world English welcome here – and the reality of the published lexis – a certain amount of robust editing. Dr Burchfield also needed his dictionary to be noticed (so did Murray, so any maker of what is not exactly literary sex on a stick) and Dr Ogilvie acknowledges the fact. But she makes a point of eliminating any suggestion that he lied. If her opinion differs from his, then it is for the best of lexicographical reasons: the detailed analysis of the material on offer.

My learned friends (who are definitely not lawyers but truly learned, and indeed friends and better qualified to consider this tale then am I) have already written about the story and the book. (Here and here; Dr Ogilvie has offered her own response in the Huffington Post). I leave you to consider both story and rebuttals. Better still you could read the book.

Sarah Ogilvie Words of the World: A Global History of the Oxford English Dictionary (CUP £17.99)

I find interesting the fuss that occasionally stirs up around lexicography, though not quite interesting enough to run out for Ogilvie’s book, or the new book in the US about Webster’s Third. I suppose that we all, by virtue of long acquaintance, come to imagine ourselves authorities on the English language, silently inserting a “this” into “Since the memory of man runneth not to the contrary.”

Newsnight covered this story with a debate between Philip Hensher and poet Simon Armitage. The angle they seemed to be trying for was that Burchfield was a xenophobe, or possibly even a… racist! Probably just as well you don’t have a telly, JG.