Three of the great British composers all died within a few months of each other. Mahlerman looks at what we lost in 1934…

Last week we celebrated the ongoing second Elizabethan age, sixty years and counting. The first, ending with the death of Gloriana in 1603, was marked by an extraordinary burst of creativity in literature and music – not just Shakespeare, Marlowe, Donne and the rest but, leading up to the short life of Henry Purcell 100 years later, Queen Bess presided over a magical group of musicians the equal of which has not seen since in this septic isle; Byrd, Gibbons, Dowland, Thomas Morley… there are many more. It should have been the foundation upon which we built an empire to equal that of Germany in the 18th and 19th Century, but somehow it didn’t happen. And when in 1934, within a few short months, we lost Elgar, Delius and Gustav Holst, the cloth was pretty threadbare – save the great modalist Ralph Vaughan Williams, whose instincts were to look back at the autostereotype of Merrie England. Let’s remind ourselves of what we lost.

Anyone who doubts the genius of Edward Elgar should perhaps invest the four and a half minutes it takes to listen to the grave beauty of Sospiri (‘Sighs’), the composer’s Opus 70 for String Orchestra, harp and organ. Gone is the triumphalism and bombast that mars some of his earlier works. Here, and in some of his late miniatures for orchestra, the true heart of this complex Colonel Blimp character is revealed. The jingoistic Pomp and Circumstance and the masterful Enigma Variations brought him worldwide recognition and wealth but for many, the beginning and end of this great Edwardian gentleman is the deeply felt Oratorio set to the poem of Cardinal Newman, The Dream of Gerontius. If only we had the space and time for that today.

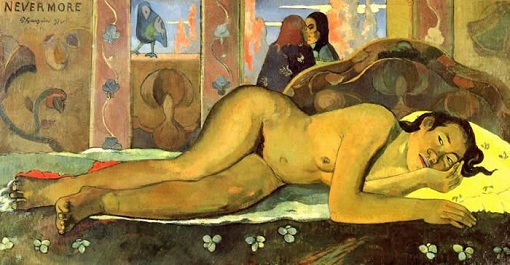

If we are mostly concerned on Lazy Sunday with classicism in music, then it could be said that the work of Fritz (later Frederick) Theodore Albert Delius represents its polar opposite. A clear framework, a regular pulse, economy of means – all are absent in this most personal of composers. And as the conductor Andrew Davis said in John Bridcut’s recent film on Delius, the best music we know seems to ‘go somewhere’. The music of Delius ‘just sits there, sounding beautiful’. But in the same way that the music of, say, Tchaikovsky, is not for every day, so it is with Fred, that on some days only Delius will do. The gently lapping rhythms, the extreme fluidity of Sea Drift, In a Summer Garden and On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring are what we might turn to for consolation at these moments. Above is the marvellous painting Nevermore by Paul Gauguin, an artwork that Delius once owned, and a reminder that this often limpid music was created by a rampant libertine, whose early life in Florida and Paris was disfigured by his unchecked desires – desires for which he paid a heavy price in the syphilis he contracted. By his mid sixties he was paralysed and blind, and only able to compose with the aid of his amanuensis Eric Fenby, and the support of his long-suffering wife Jelka.

The musicologist Anthony Payne, famous for his work on Elgar’s 3rd Symphony, believes that the North Country Sketches, composed just before the First World War, represent the high-water mark of the Delius output. Inspired by the Yorkshire Pennine Dales where his life began, here is Winter Landscape, the second of four movements.

English on his mother’s side, Swedish on his father’s, the music of Gustav Holst seems to emerge from a wellspring of its own making, tipping the hat to no man. Hugely admired by musicians he has never, except in one work, been taken up by the musical public. The Hymn of Jesus is heard from time to time, and the mysterious poetry of Egdon Heath is sometimes released as if from behind the clouds – but as for, say, his fascinating orientalist chamber opera Savitri, a sign is there none. Perhaps we should accept the fact that in the orchestral suite The Planets, the inspiration level was absolutely white-hot, and that this marvellous piece deserves the universal popularity it has achieved in the last 100 years. The big tune of Jupiter was wheeled out last weekend under Tower Bridge, but today we will marvel at the audacious imagination of Host in the drifting, whispering beauty of Neptune, the Mystic, with the composer’s concise instructions for the fading of the wordless women’s choruses that they should be ‘placed in an adjoining room, the door of which is to be left open until the last bar, when it is to be slowly and silently closed’.

Thank you once more, MM, for this lovely post. Neptune is my favourite Planet.

Wonderful stuff, as usual. Sospiri is an old favourite of mine, along with Elgar’s Mina, an orchestral miniature that purports to be a musical portrait of the composer’s cairn terrier. (It’s no dog, though, in my opinion. I think it’s either a self-portrait or a portrayal of one of those upper-class ladies that Elgar admired from near or far.)

Oddly enough, Holst’s Savitri is being given a rare performance at this year’s Cheltenham Festival, in about a month’s time. Cheltenham was where Holst was born, and it’s interesting that this town, famous as the place where the colonels and administrators of the Raj came to retire, should have given birth to a composer who steeped himself in Indian literature and philosophy.

A lovely post. Three great composers; three wonderful pieces. The post has, for me, pointed up the uniqueness of Delius and, without exaggeration, it has reignited my interest in his work, which has sat undisturbed in my collection for too long.

Sospiri is beautiful; yet so overwhelmingly sad. Is it Elgar’s deepest sigh for a Europe about to be engulfed by utter misery? It’s easy to imagine him saying to the work’s dedicatee, W H Reed: ‘This is complete madness; everything we hold dear is under threat, and we can do nothing to influence it.’ Glorious music; I suspect the great funeral director who lurks in my imagination might put it to me: ‘Fancy a bit of My Way, Angels, Forever Autumn, Over the Rainbow?’ I’d say ‘No thanks, just give me Sospiri. Then let’s hope those present will be able to cope with the emotional surge of it all.’

Thank you Brit – and thank you for keeping your latest Uranus jokes in the box.

Yes PW, emerging as Elgar did, from a period when you kept your passions on a tight rein, it is hard to square what we hear in this devastatingly sad piece, with the starched-collar image of the composer in his plus-fours, off to the races. The opening chords are as atmospheric as anything I can recall in music.

When you eventually blow the dust off your collection JH, the ebb and flow of Sea Drift would be a good place to (re) start……I think I’ll go and crank-up Spotify right now.