Mahlerman continues his fortnightly guide to serious music by looking at three great second symphonies…

In the summer of 1802 Ludwig van Beethoven, as was his pleasure, left Vienna for the peace of the countryside, settling in the small hamlet of Heiligenstadt a few miles away. Just 32 years old, with a growing deafness unexplained, he fell into a slough of despondency, producing the now famous Testament reflecting his bleak mood, and going on to set down what amounted to a last will, favouring his two brothers.

What amazes us most about this period in his life is not the self-pity and lamentation that this great genius expresses in the document, but the complete contrast it reveals with the music he was composing at the same time. The Symphony No. 2 in D Major, perhaps the least played of the nine, and certainly the least appreciated, is one of Beethoven’s most beautiful and uplifting creations and, though hardly revolutionary, it does contain some of the footprints that found greater expression in the E flat ‘Eroica’ that followed a couple of years later, closing the door on the 18th Century for ever.

Hector Berlioz, a great writer on, as well as of, music, commented that ‘this symphony is smiling throughout’, going on to add that in the short Scherzo third movement, ‘The composer still believes in immortal glory, in love, in devotion. What abandon in his gaiety! What wit! What sallies!’ Florid language from this French Romantic, but perhaps it will persuade you to lend an ear to the other three movements of this neglected masterpiece.

The shadow of Beethoven fell across the life of Johannes Brahms in such a profound way that he devoted almost twenty years of struggle and anguish creating, and finally delivering his first symphony in 1876 when he was already in his mid-forties, thereafter having to endure the inevitable tag that it received as ‘Beethoven’s Tenth’. Stormy and popular masterpiece that it is, it remains the least successful of the quartet of symphonies that Brahms composed, and he followed it within a year with the beautiful Symphony No. 2 in D Major.

Criticism of the Brahms symphonies usually centers on their lack of strong contrast, and it is true textually and in terms of their modest tempi and easy-going nature. The upside is that the composer’s vivid dramatic sense, and his gift for melody, are concentrated in these four works as perhaps nowhere else in his large output. Not a classicist, nor a romantic, the appeal of Brahms is that of a romantic spirit controlled by a classical intellect. A lifelong bachelor, very little is known of his emotional life – outside composition. He continued a lengthy, platonic, emotional relationship with Robert Schumann’s wife Clara, who championed much of his music. Physically striking as a young man, his good looks quickly gave way to the traditional image we have of him as a portly, bearded grump, hands clasped behind his back, pacing the countryside around Vienna lost in head-composition, his favoured method of creation.

I don’t need much of an excuse to listen to Carlos Kleiber conducting Brahms (or anything else); here he is with the Vienna Philharmonic in 1988, live in the Musikverein playing the final movement of this marvellous work.

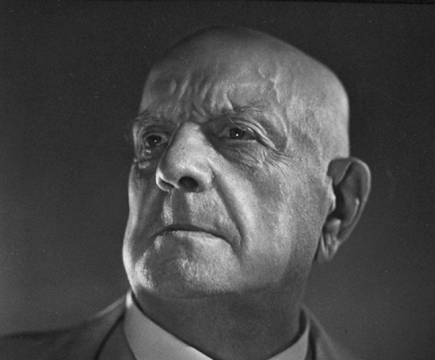

Northern Europe has produced a handful of very fine composers over the last 150 years, but just a couple who have an indisputable claim to greatness and, by chance, they were exact contemporaries. The Dane Carl Nielsen was virtually unknown in England until his amazing fifth symphony was performed at the 1950 Edinburgh Festival. The stir created was enormous and now most of his symphonic output is well known to music lovers. But towering above even this great master is the Finn Jean Sibelius [pictured, top]. That a composer of his stature should emerge from a country with a sparse population in the frozen north, makes his domination of symphonic form in the 20th Century more extraordinary still; where did he come from?

His early orchestral suite Karelia and later tone-poem Finlandia became enormously popular, and remain staples of the concert hall today, but they are relatively trivial. His real legacy began with the Tchaikovskian First Symphony and later Violin Concerto, both of which are influenced by the great Russian. But even at this time, in the last couple of years of the 19th Century, the Sibelius ‘voice’ was already formed, and when he produced the Symphony No. 2 in D Major early in 1902, the aroma of Beethoven and Borodin had vanished, to be replaced by the modal sway of Palestrina. The birth of this symphony is, quite naturally, the opening of the first movement, with a distinctive rising, three-note motif. What the composer does with this small idea over the 40 minute span of the symphony convinces me of his genius.

In January of this year the Finnish conductor Paavo Berglund sadly died, aged 82. I was fortunate enough to hear him conduct Shostakovitch, Tchaikovsky and Sibelius, the composer that his name is most often linked with, and I will not quickly forget these performances, often with second-line orchestras. He knew Sibelius, but not well (did anybody?), and had this music in his blood; paired here with the Helsinki Philharmonic in the Allegretto First Movement, we are as close to Sibelius Heaven as makes no difference.

The backdrop is the Sibelius Monument in Sibelius Park, Helsinki, and the curious whistling prelude on the vid is presumably the icy wind blowing through the 600 steel pipes.

gosh, with the exception of Mussolini, has ever a head lent itself more to solid statuary than Sibilius’? What a noggin! The sound of the pipes at the start of the Allegreto is wonderfully chilly and matches the sound of the wind currently battering my humble abode. Does the monument count as an aeolian harp I wonder?

Loved the beethoven, great performance

Yes Worm – and your comment put me in mind of a famous one made by the pugnacious Sibelius himself ‘pay no attention to what critics say; there has never been a statue in honor of a critic’.

Until the last third of his life when doubt set in, he knew his worth, and had little time for modesty.

Ah, Sibelius’s 2nd. Sublime stuff MM. Do you perform an IPod filling/loading/stuffing service for lazy, unimaginative and uncultured buggers like me? I’m beginning to feel that if I just left it all to you I would never have to worry about what to listen to again.

Hope your enjoying watching the Spanish go down the Swannee in the company of the finest graduates of HMP Slade.

Well Recusant, for a smaller fee than I receive for doing this (wait a moment, that would mean I would have to give you money), I would be happy to provide you with a ‘playlist’, but I have to warn you that I am not a big fan of the iPod, nor the tsunami of noise that we are subjected to daily, much of it uninvited. Good music only reveals its hidden beauty when we give it the attention it often merits – as you probably did with the Sibelius. Earphones also give a false ‘picture’. A modest stereo set-up will create a wonderful ‘soundstage’ in front of the listener, with ‘information’ from left/right arriving to both receivers on the side of your head (not just left-to-left) Was it Mitterrand who said ‘we need to give time time’. I’m with the old two-timer.

No worries, MM, I just used the word IPod as a catch-all. Earphones give me earache and I have a curmudgeonly reluctance to worship at all things Apple. Just keep up the Lazy Musicing and my list shall eventually be filled. And know that some of us swine who you cast pearls at appreciate it……………..

The Beethoven is wonderful (A voice in my head screams “Of course it is, idiot, it’s Beethoven!”). The movement you’ve chosen, MM, is a favourite; for me music at its most joyous, especially when played on period instruments. I have the Norrington/London Classical Players recording and I think that a producer planning a film on the life of Mohammed Ali should consider Norrington’s scherzo as accompaniment to early film of the then Cassius Clay mesmerising opponents with dazzling footwork then picking them off with flurries of punches. It fits, it really does, doesn’t it? Well, it does for me.

The Sibelius is wonderful (A voice in my……………….Oh do shut up). I have to smile when I re-visit Eric Tawaststjerna’s biography in which he tells us of the great man’s first visit to England: ‘Sibelius landed at Dover on 29 November and underwent a body search on the part of His Majesty’s Customs and Immigration who promptly fined him two pounds and six shillings for trying to smuggle in some cigars. At Victoria he was met by Bantock for whom he had an immediate sympathy.’

I include that final sentence simply to pick up the splendidly named composer Granville Bantock who championed the second symphony in Britain and just about everything else by Sibelius. If you ever post on neglected British composers, MM, I hope Bantock will feature: the Hebridean Symphony and the Celtic Symphony are marvellous works