Queen Gin: Oh! what is is this that runs so cold about me?

A dram! — a dram! — a large one or I die.

’Tis vain [drinks hastily]

O, O, Farewell [dies]Mob: What, dead drunk or dead in earnest?

[finale of The Deposing of Queen Gin, with the Ruin of the Duke of Rum, Marquee de Nantz and the Lord Sugarcane, &c. by Jack Juniper]

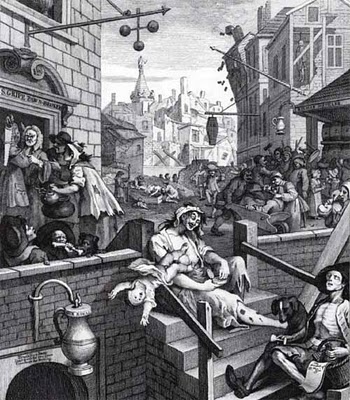

Those were the days, eh? Gin in parliament (with a much-reviled act which engendered those lines; nantz by the way being brandy, from Nantes), gin on stage, gin in ballads, gin in the press and of course gin in Hogarth’s Gin Lane – the one with the poxed drab, the falling baby, the skeletal lush, the collapsing house, the run-down pawnbrokers and similar snapshots of Merrie England. And gin wasn’t even gin. Not like what they mix with tonic at the cockers-p. or turns up in your over-priced ‘Shove-Me-Up-Against-the-Wall-Rip-My-Clothes-Off-and-Sod-That-You’re-Too-Pissed-to-Manage-It’ down Ayia Napa. No. Gin was genever, which was Dutch for juniper and thus en-slanged as Hollands or the Dutch drop or Geneva (even if that is in France) and a heavy drinker was taking his drops or reading Geneva print.

Nor was that all. far from it. It was Old Tom which memorialized Thomas Norris, who was employed at Hodges’ distillery and who opened a gin palace in Great Russell Street, Covent Garden. It was daffy, not because that was its effect (though it was) but from Daffy’s Elixir which was otherwise a proprietary remedy popularly merchandised as ‘the soothing syrup’. It could also be duffy, which also stood for a quarter pint measure, or it was deady, again nodding to its effects, but this time from a distiller, one D. Deady of Sol’s Row off Tottenham Court Road. Tom and Jerry, in Life in London, went to East to debauch at All Max, which not only punned on the West End’s fashionable Almacks but played with max or old max, which meant gin. A max-ken sold the stuff and the drunken clientele were maxy.

It was transparent; it came in colours: blue or white; some saw it as a form of textile. The first led to brilliant, which was raw and undiluted (raw was another name), and clear crystal and thence flash or strike of lightning or thunder and lightning (which added bitters) and strikefire. Transparency gave see-through which moved on to whiteness, and asking for white port or white wine in the wrong tavern might not get what you expected. The ‘port’ and ‘wine’ were meant to be euphemisms, so was the later twankay or twankey which in tea trade jargon meant green tea and might be the origin of the pantomime dame Widow Twankey. Bunter’s tea referred to the bunter, a run-down old whore or a female rag-scavenger.

It could be true blue or light blue and a century on bluestone which in standard English means copper sulphate or even sulphuric acid. The textiles suggested smoothness and were coloured as well: blue or white ribbin, i.e. ribbon, which played on the earlier blue or white tape (which might have been underpinned by taphouse) which could also be red tape (though ‘red’ in drinks was usually brandy), and white velvet or satin (later appropriated by Sir Robert Burnett). A yard of satin or of tape was a glassful. The main blue was blue ruin, which had the same effect on mother, though another synonym was mother’s milk, as were cold cream and cream of the valley.

Less appealing was rag water, so called as Captain Grose explained because ‘these [are] liquors seldom failing to reduce those that drink them to rags.’ Not that one might always boast even a rag: stark– or staff-naked suggested raw alcohol, ‘unclothed’ in congeners or mixers, not to mention the poverty of its drinkers. Strip-me-down naked was synonymous. Some saw it as an universal panacea: meat-drink-washing-and-lodging.

The effects provide a regular flow of imagery: busthead, crank (which ‘mixed gin with water and ‘cranked you up’),kick in the guts, roll-me-in-the-kennel (a kennel being a gutter), gunpowder (you head ‘went off with a bang’), heartsease, kill-grief (but also kill-cobbler which suggests a professional propensity), tittery, which in dialect meant tottering along on the verge of collapse, and wind which ‘caught your breath’. Diddle was another one that meant unsteadiness, and the diddle-cove or –spinner was the landlord of a diddle-ken. Then there was the simply uncompromising: ruin, misery or poverty, though royal poverty suggested that at least for a while you would ‘feel like a king’. Much later came South Africa’s Queen’s tears, a Zulu term back-referring to the tears Queen Victoria supposedly shed after her troops’ defeat at Isandhlwana in 1879.

As in the martini (not to mention the camp if defunct English martini wherein tea is mixed with gin), gin works as an ingredient. There’s the dog’s nose: beer warmed nearly to boiling, mixed with gin or wormwood (the basis of absinthe); absent wormwood, substitute brandy. Another gin-and-wormwood combo was purl (possibly linked to standard purl, a rill or whirl of water) which used the dog’s nose ingredients plus sugar and ginger. It was a popular morning pick-me-up and a cut-down version, early purl simply heated beer with gin. Gin and beer could also be huckle-my-buff or –butt which uses dialect’s huckle, to jog along, thus making it literally ‘jog my skin’ or ‘my buttocks’. Piss quick – either from its resemblance to urine or its possible micturative effects – is gin mixed with marmalade topped up with boiling water. Twist blends brandy and gin.

Ever-popular was hot, described by George Parker in his London guide Life’s Painter of Variegated Characters in Public and Private Life (1789) as ‘a mixed kind of liquor, of beer and gin, with egg, sugar and nutmeg.’ He added that it was ‘drank mostly in night-houses, but when drank in a morning, it is called flannel.’ Like the material flannel ‘kept you warm’ and if you were wrapt in warm flannel you’d had too much. An older name, which underpinned flannel, had been lambswool. And for the really desperate, there was alls, which came either from ‘all nations’, as in ‘flags of…’, or more basically ‘all the leftovers’. (Up the market Victorian wine merchants talked of omnes, the odds and ends of various wines). Either way it consisted of the dregs collected from the overflow from the pouring taps, the ends of spirit bottles and similar leavings; it was sold cheap in gin shops where female customers, misogynists claimed, were particular devotees.

‘Ye link and shoe boys clubb a tear,

Ye basket-women join;

Grubb-street, pour forth a stream of brine,

Ye porters hang your heads and pine;

All, all are damn’d to rot-gut beer.’Timothy Scrub Desolation, or, The Fall of Gin 1736

okay…so you say ‘gin’ was made with juniper but wasn’t like today’s gin?? Do you mean in the sense that it wasn’t 40% smooth stuff, but basically meths/ pure alcohol with a juniper flavour?

Also, I have heard that rum, as in the stuff that salty sea dogs drank was not ‘rum’ as we know it now either, but just a spirit of sorts, so what was the difference in production between 18th C. ‘gin’ and ‘rum’? were they bascially the same thing??? I’m confused

I think this was possibly lexicographer’s license – distant from its artistic cousin in that artifice substitutes for the art – but this is what the current OED (2009 revision) says at genever:

A clear alcoholic spirit from Belgium and the Netherlands, distilled from grain and flavoured with juniper.

Originally used to designate the spirit as manufactured in the Low Countries, with the shortened form gin used to distinguish a British imitation of this, usually flavoured with a variety of spices and aromatics in addition to or in place of juniper; the two words are, however, often used indiscriminately.

In many works of reference in the 18th and early 19th centuries described as being distilled from fermented juniper berries; this practice is obsolete, although juniper berries are occasionally added to the malted grain mash before fermentation and distillation.

The unrevised (1989 or earlier) entry for gin says:

An ardent spirit distilled from grain or malt; see genever n. and the note there.

As flabbergastingly fascinating a post as ever, Jonathon. I once drank potato gin in Poland – can’t recall much about that occasion. And I once almost killed an aged aunt with one of my curiously strong G&T’s (far from Ayia Napa) – must have been Rag Water.

There used to be something in my youth called Polish Pure Spirit which bore what seemed a phenomenally high proof number and at which I recall we schoolboys ogling but never daring obtain.

As for your G&T, it sounds very appealing.

My grandad always put angostura bitters in his G&T. Doubt the Sipsmith boys would approve, they were terrible fascists about mixing.