Continuing our series looking at great paintings housed in London’s National Gallery…

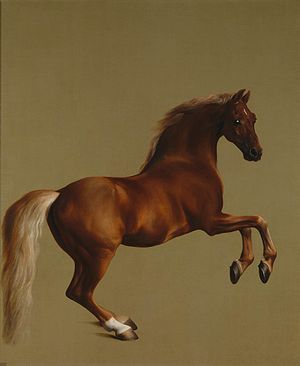

I took my youngest son to the National Gallery last week. As we stood before Stubbs’s Whistlejacket I asked him what he thought: “It’s a bit scary, Daddy”. I could see his point.

Stubbs’s series of paintings depicting a horse being surprised and attacked by a lion (Horse Frightened by a Lion, A Lion Attacking a Horse) is usually taken as the contemporary demonstration of Burke’s theory of the sublime in art: how witnessing the terrible can produce an ultimately satisfying aesthetic sensation:

The passion caused by the great and sublime in nature . . . is Astonishment; and astonishment is that state of the soul, in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror. In this case the mind is so entirely filled with its object, that it cannot entertain any other.

Despite a hint of nervous fragility and the almost coquettish turn of the head, there’s something of this in Whistlejacket. The lion/horse encounters are the sublime as narrative – it’s thrilling to see, frame by frame, a lion preying on a terrified horse (in fact, this sort of thing is a YouTube favourite). The portrait of Whistlejacket, on the other hand, is more subtly sublime, it shows rather than tells. It’s a purer representation: he’s a thrill in himself.

It also happens to fulfill a couple of Burke’s criteria for the sublime not present in A Lion…: it possesses qualities of vastness and of the infinite. The horse is literally vast, mountainous, at least for a painting (he’s life-size), and he’s placed in infinite space. He’s entire, a stallion rearing alone on an unbounded field of neutral colour; there’s no background, no context, nothing present to distract us and by which he can be diminished.

Another important element: he has no rider. Unlike nearly all representations of rearing horses, from Classical times onwards, there’s no regal personage astride him. He’s literally nature unbridled; the star, not a supporting actor. (Of course, Whistlejacket also happens to be an astonishingly lifelike representation of a horse, from the bulging veins on his muzzle to his feathery tail, but that’s another story).

Incidentally, both Burke and Stubbs found a backer in the 2nd Marquess of Rockingham who, through his sponsorship of these two individuals, has a good claim to be the greatest patron this country has ever seen.

Burke, of course, went from theorising on aesthetics to become the greatest critic of the French Revolution, for him a source not so much of sublime terror as of Terror outright. It’s fitting perhaps that Napoleon, the Revolution’s culmination and nemesis, was portrayed at the height of his powers triumphantly crossing the Alps on a rearing stallion. Napoleon Crossing the Alps by Jacques-Louis David (below) is painted with the same Romantic intensity as Whistlejacket but with the horse more traditionally mounted by a great man, one who was in the business of mastering Alps and armies, as well as horses.

But then Whistlejacket – and Burke – have the last laugh, I think: after a great deal of rather crazed destructiveness, Napoleon came to a sorry end. Proof that the sublime should be reserved for horses and mountains and suchlike.

Wonderful musings, Gaw. I mentioned Whistlejacket briefly in the Skating Minister episode. It’s a pure example of the appeal of physical form, isn’t it? I suppose that (a long way) after the female nude, the equine form is the most pleasing to the human eye…

what I like about Whistlejacket compared to many of the other Stubbs horse paintings is that it seems to be one of the most realistically proportioned of his horses. (many of the others have impossibly slender necks and tiny heads) Also it’s nice to see a Stubbs without his usual backgrounds of arcadian frothy trees (a la Claude) for a change

I’ve never known what to make of the painting’s lack of a background. I’m not a horsey person, but you’ve kinda explained it to me, thanks.

How it came to be so lifelike, as well as the various theories about its peculiar features (including the lack of background), all make for fascinating reading.

BTW I removed the reference to Burke being ‘very English’. Of course, he was Irish. But as he practically invented what’s become a characteristically English way of thinking about the world this can slip one’s mind (incidentally, Conor Cruise O’Brien’s biography theorises brilliantly on the significance of Burke’s Irish background – funny how the Celtic and English mixture so often produces the best fireworks).