From football to fish and chips, from tabloids to faithlessness – a remarkable number of facets of modern British life can be traced to the ‘Age of Equipoise’, and specifically to the year 1860, argues Henry Jeffreys…

In 1860 a Jewish man called Joseph Malin in the East of London had a brainwave. His idea was to combine the traditional Sephardic way of cooking fish in hot oil and batter with the latest potato technology from Belgium, the chip. In doing so, he may have made a vital contribution to national stability.

In the early years of Victoria’s reign, Britain had been a turbulent place. The coming of the Industrial Age had radically upended many of the old ways of life, especially where the poor were concerned. Crime increased drastically. The movement to extend the vote turned violent. Was the country headed for revolution? Marx predicted as much. And yet rather than winding up in a bloodbath, Britain entered a period of social and political calm that became known as ‘the Age of Equipoise.’

Did Malin’s idea help to keep the peace? The British have always had a soft spot for junk food, and for a long time no dish was more cherished than a cod supper. As George Orwell would one day comment, there would never be a revolution as long as the lower classes had fish and chips. Junk food, not religion, was the opium of the British people. The role of religion was in fact partly a political one, and this might also explain the relative peace. Nonconformists, especially Methodists, were involved in the organisation of labour. Class war was mediated by Christian values, and the labour movement gained small victories incrementally rather than opting for violent revolution. In 1860 alone picketing was legalised and the London Trades Council established, both major milestones for the trade union movement.

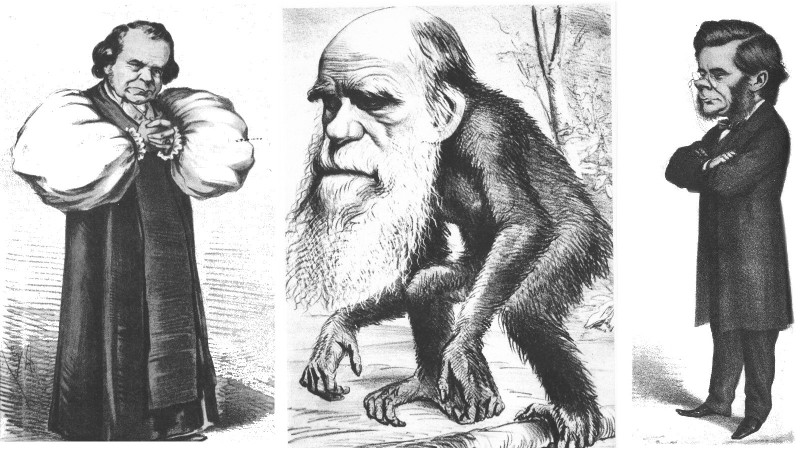

Christianity was not always so temperate. On the 30th June 1860 thousands thronged Oxford University Museum to hear a debate on Darwinism. A scientific and metaphysical revolution began with the 1859 publication of Darwin’s The Origin of Species. The debate was between the proponent of Darwin, Thomas Henry Huxley, and speaking against Samuel Wilberforce, son of the great abolitionist and dubbed Soapy Sam by Benjamin Disraeli for his oleaginous manner. It was a bad-tempered and passionate debate with both sides claiming victory, though most contemporary observers suggest that the Darwinians took the day.

When, in 1860, the writer J. Ewing Ritchie wrote ‘what would the Englishmen do without his newspaper I cannot imagine,’ he didn’t just mean that they’d be stumped for somewhere to put their fish and chips. Titles such as the Daily Telegraph, the Times and the Manchester Guardian were booming, as were their downmarket cousins, which offered up a familiar swirl of murder and prurient sexuality, preferably both at the same time. The News of the World ran with lurid headlines such as ‘Extraordinary Case of Drugging and Violation’, concerning a woman who was drugged, raped and thrown in the Thames. These ancestors of modern tabloids were sold on the streets by gangs of urchins.

A few months after The Woman in White had twisted its last twist, Great Expectations was also serialised by way of Charles Dickens’ magazine All the Year Round. Serialised novels fulfilled the role of soap operas and TV box sets. They were an equally transatlantic phenomenon although generally the other way round to today, with American audiences having a huge appetite for British stories. The two were closer than ever before: advances in steamship technology had cut transatlantic crossing times to roughly eight days. It was exhaustion following a gruelling American tour that would, a decade later, send Dickens to his grave.

One of the era’s most successful novelists was Mary Elizabeth Braddon. But the author of Lady Audley’s Secret had a dark secret: she moonlighted as a writer of so-called penny dreadfuls. These were lurid and often supernatural serials that sold, naturally, for a penny an episode. The titles gave you some idea of what to expect: Varney the Vampire or Feast of Blood, for example, was a great influence on Bram Stoker. One of Braddon’s own penny dreadfuls, The Black Band, was about a secret society of Italian revolutionaries (FOOTNOTE: The Black Band or, to use its full title, The Black Band, Or, The Mysteries of Midnight also features an Austrian gangster whose brain is gradually being melted by poison and an investigator named Joseph Slythe who manages to infiltrate the Black Band).

It was a well-chosen subject matter. The Italian peninsula and its revolutionary battles loomed large in the public imagination. One of their number, Giuseppi Garibaldi, was the greatest celebrity of the age. He was a veteran of several failed uprisings so when he landed in Sicily with a mere thousand men clad in red shirts, few gave him much chance of success. Instead, he somehow defeated the forces of the King of Naples and then, with British help, landed on the mainland. To the astonishment of a world that was following his exploits in the newspapers, he managed to inflict further defeats on the Neapolitan army and eventually joined up with friendly forces to the north. The following year, Victor Emmanuel II of Piedmont (the man on whose behalf he fought) was crowned King of a newly united Italy. Garibaldi is not only immortalised in the eponymous biscuit. His exploits, and those of his army of redshirts, have an echo in the strip of Nottingham Forest Football Club, keen to claim the revolutionary associations of so-called ‘garibaldi red’.

It was a revolutionary time for narcotics, too. In Germany, a chemist by the name of Albert Niemann isolated an alkaloid contained within the coca leaf and gave it the name ‘cocaine’. And in 1860, the Second Opium War with China concluded at the treaty of Peking, leading to the legalisation of the opium trade and opening up China to European capitalism and Christian missionaries. Opium was prevalent in Victorian society in a way that it’s difficult for us to fathom today. It was available without restriction over the counter. It was in patent medicines. Mothers sometimes gave babies remedies such as Godfrey’s Cordial, a mixture of opium and molasses, to help them sleep. Mrs Beeton, for heaven’s sake, included recipes containing opium in her cookbook. Perhaps it might be an explanation for the Age of Equipoise.

Once you know how much opium was about, it’s hard not to see morphine-induced hallucinations in mid-Victorian art rather as 60s pop art was infused with LSD and marijuana. There are the terrifying woodcuts of Gustave Dore and some of the pre-Raphaelites work is decidedly trippy. Willkie Collins took laudanum – a mixture of opium and alcohol – to deal with a case of gout so severe that one onlooker described his eyes as ‘literally enormous bags of blood’. But his laudanum-induced visions were like something from a penny dreadful: he was plagued by a doppelganger and a green skinned woman with tusks. Cocaine and opium could relieve pain but the art of medicine, of actually treating diseases, was still in its infancy. That said, 1860 saw the opening by Florence Nightingale of Britain’s first school of nursing at St. Thomas’s Hospital, Southwark.

Elsewhere in South East London, a house was completed that would transform British cities, or at least their vast and porous edges. The Red House in Bexleyheath, a collaboration between designer William Morris and architect Philip Webb, was built to demonstrate an alternative to the horrors of industrialism. Morris was, of course, the founder of the arts and crafts movement, with its dream of a return to the craftsmanship of a pre-industrial English past. Yet ironically the Red House proved an inspiration for miles and miles of identikit suburbs that would soon spread out of Britain’s cities to cater for the ever-expanding middle class. For them, the Age of Equipoise was a time of contentment and advancement. As Jane Aster wrote in Habits of Good Society: A Handbook for Ladies and Gentlemen: “The circles of good society are growing wider and wider, admitting repeatedly, and more and more than ever, men who have risen from the cottage or the workshop”.

A century and a half later, The News of the World is no more and fish and chips have largely been usurped by fried chicken, but we still live in Victorian suburbs. So how much has really changed? Drugs and junk food remain popular forms of entertainment, and we still binge on serialised stories and trashy news. The religion versus Darwin debate rumbles on. What is enlightening about the year 1860 is that, back then, these things were all brand new. It would be too much to say that this was the birth of the modern world, but much of what we take for granted, or even consider hackneyed, has its roots in the Age of Equipoise. And despite everything, Britain is still a peculiarly peaceful place today.

A version of this article originally appeared in the Happy Reader.

It was also the year Americans invented two things that illustrate our modern “curse or blessing” ambivalence about technology—the vacuum cleaner (carpet sweeper) and the repeater rifle.