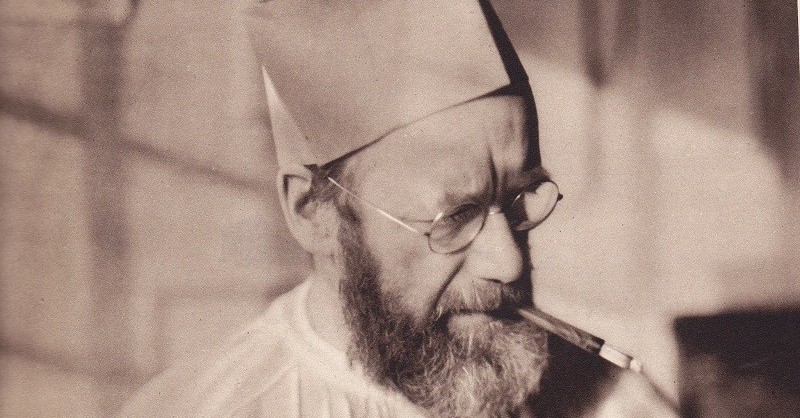

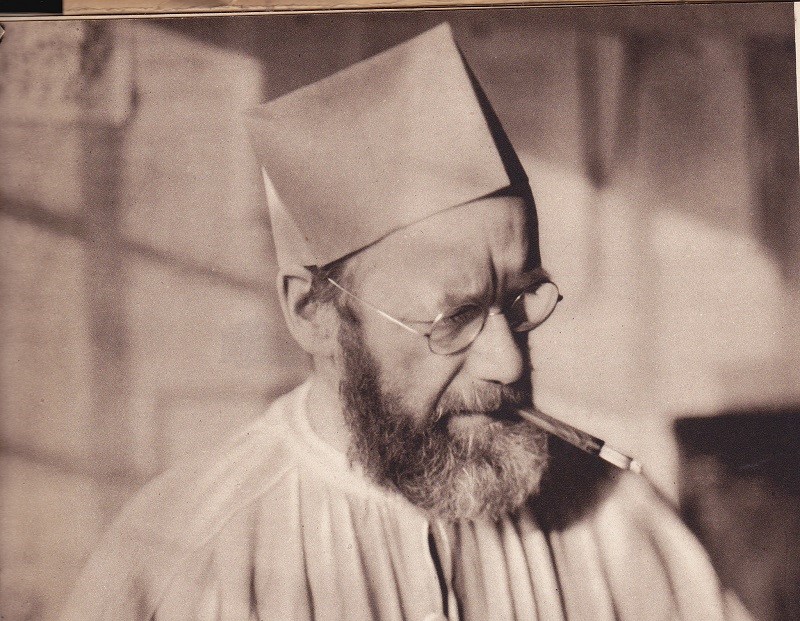

It is difficult to know what, exactly, to make of the sculptor Eric Gill, what with his indiscriminate sexual appetites and belief that all art was meaningless unless understood as an expression of religious conviction…

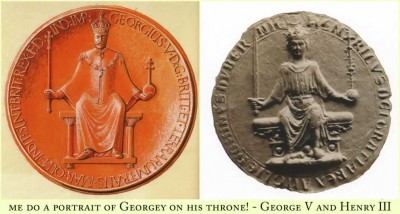

In 1914 Eric Gill submitted a design – of George V astride a urinating horse – to the Lord Chancellor’s office, intended for the Great Seal of the Realm. It was his third attempt, and it looked like this:

Gill was excited to receive the commission. “Me do a portrait of Georgey on his throne!” he wrote to his friend, the artist William Rothenstein; “Did you ever see the Great Seal of Henry III – 1230? It’s a bloody marvel.’ He had been looking at this and other seals in the British Museum, and his first rejected design was based upon it.

The second design, derived from the Great Seal of Oliver Cromwell of 1655, was also rejected (and not, so far as we know, because of the Cromwell reference). For his third attempt he stood the horse stock still, extended its rigid back legs in a manner typical, it seems, of a urinating horse, and set Georgey upright and preposterous in the stirrups, as though aiding his steed’s micturition.

The design was accepted, though it would presumably have needed the final approval of the King, and someone up the lugubrious chain of State with greater knowledge of the demeanour of horses may in the end have noticed the snook-cocking; but anyway the project stalled with the advent of war, and the seal was never cut.

It is hard to know what to make of Gill, taken all round. His artistic reputation has been if anything enhanced by the revelations in the 1980s of his vast, indiscriminate and, as he himself had it, anti-bourgeois sexual appetites, which included incestuous and abusive relationships with his sister and daughters, and what his biographer describes as an ‘experimental connection’ with his dog. He believed that all art was meaningless unless understood as an expression of religious conviction, and for a period in the 1920s would only work with fellow Catholics.

He was also, unquestionably, one of the great modernist sculptors of the early twentieth century, the finest letter cutter of his day, and a highly original designer of typeface (responsible among other things for the fonts Gill Sans, Joanna and Perpetua). In each of these disciplines he consulted not only his whimsical disposition, or his socialist politics, or his Catholic heterodoxy – the peculiar blend of abilities and dispositions and beliefs that constituted his own originality, in other words – but also picked ceaselessly and perceptively over the great midden of the past, piled up in museums and other collections. Coins and medals and Great Seals, to take only an example, numbered among the scattered remnant, the invaluable spoglia, of vanished or fading cultures and traditions.

The composer Jean Sibelius famously said that music was a mosaic designed by God and thrown down [somewhat petulantly?] in fragments to earth; the job of a composer was to collect it together, sort through it, reassemble it. The composer or artist, conceived of in this way, is a passive and dutiful figure, albeit one alive to the mystical scintillation of his or her work; Gill was conspicuously neither passive nor dutiful, but he might, anyway, have approved the notion that art, and craft, and design, were not the product of a creative imagination ex nihilo, the hair-pulling soul-dredging piano-bashing psychomachia of romantic imagination; but rather the outcome of a lengthy process of discrimination, of assembly, and of (not-overly-respectful) transformation.

I believe that Gill’s small act of sedition has much to teach the nascent republic of Norbiton regarding, among other things, the proper use of medals, seals, stamps and coins, which might otherwise only testify to the malign influence of Emperors, Kings and other despots. Were we in a position to devise our own coinage, say, or cut our own Great Seals (for ritual chucking in the Thames, perhaps), I hope we would somehow manage Gill’s neat trick – part slight of hand, part mental reservation – of precisely respecting and precisely disrespecting in the same laconic gesture.

It anyway amuses me to think that among the tesserae now available for our own recombinations, is one of Georgey’s horse taking a piss. It’s a bloody marvel.

Prophet as predator

MALCOLM BULL

review of

Fiona MacCarthy

ERIC GILL

Faber.

0571137547

Published: 8 November 2015

http://www.the-tls.co.uk/tls/public/article1629326.ece

And here’s a TLS blog piece on Eric Gill http://timescolumns.typepad.com/stothard/2015/11/eric-gill.html – and it seems the Malcolm Bull piece linked to in the earlier column is from 1989