Jonathon Green continues his eye-popping slang tour of London with a look at St Giles, once described as offering ‘the lowest conditions under which human life is possible’…

The first time I saw the flaming mot,

Was at the sign of the Porter Pot.

I called for some purl, and we had it hot

With gin and bitters too!

We threw off our slang at high and low,

For we both got as drunk as Davy’s sow…The Flash Man of St Giles (c. 1785)

It was a leper hospital and a plague pit and the local church which stood for hygiene’s sake deep in its own fields outside the city walls was named for St Giles, a second-division Saint Francis, in this case nurturing but a single wounded deer, who was named patron saint of cripples. The spire stands in the background of Hogarth’s Noon.

St Giles, once rebarbative fortress of the rookery, the buzzman, the breed and for communication’s purposes the Greek, is now reduced to a monstrous Legoland far more leprous and pestilential in its bland nullity than anything that existed before. Does its architect Renzo Piano have a problem with slang? St Giles of canting fame is gone. Before that he and his capo Richard Rogers saw off argot’s home in Paris, substituting the flaunting pipework of Pompidou’s bloated monument on the rue Beaubourg for the winding ginnels of villainy’s ancient Cours des Miracles. No matter: architects are not linguists; their vocabularies are small, centred on synonyms for money. We must not blame them for confusing ‘build’ with ‘destroy’.

By 1750 merely impoverished St Giles had become notoriously criminal St Giles. It was the first, or most celebrated rookery, which meant a criminal slum and plays either on some metaphorical, avian criminality (and perhaps blackness), or on the verb rook, to cheat. Looking back from 1852 one Thomas Beames, writing in The Rookeries of London characterised it as offering ‘the lowest conditions under which human life is possible.’ It was largely Irish, though the church was resolutely C0fE, and the locals turned to more alluring Scarlet Women than she of Rome, even if the stereotype of Catholic piety gave it the name of Holy Land or Holy Ground. Simultaneously, like Alsatia before it, St Giles was seen as a sanctuary – even if no monarch had said so – and thus another source for ‘holy ground’. Sited mid-way between Newgate prison and the Tyburn gallows it offered passing villains, processing in their tumbril, a traditional stop-off for a last beer before moving on to choke down their ‘vegetable breakfast’. The church-wardens bought the round: it was known as the St Giles’ bowl. Some of the condemned probably knew the area already. ‘For we are the boys of the Holy Ground’ sang the balladeers. ‘We dance upon nothing and turn us around.’ Like Huxley’s Savage the hanged, still unaided by the drop’s merciful dispatch, would spin slowly in the wind, displaying what the wits termed ‘a wry face and pissen britches’. There was a local jail, St Giles’ Roundhouse, from which Jack Shepherd escaped in 1724. First of the celebrity villains he would go on to greater evasions from Newgate before he too made the fatal trip. A well-known local tenement was known as Rats’ Castle and doubtless justified its name, while the spinniken or workhouse (from the Dutch spinnhuis, literally a ‘spinning house’ and as such referring to a woman’s house of detention) was coined to define the institution in St Giles.

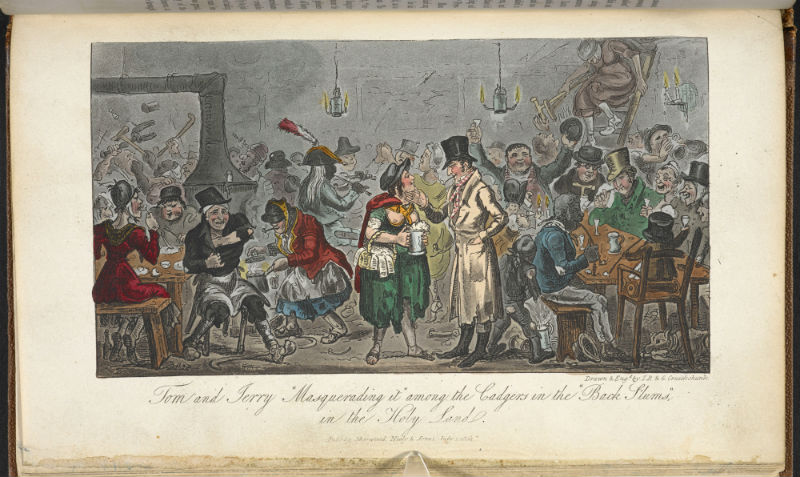

The rookery gave its due to language. Hopping Giles nodded to the saint; it meant one who limped. St Giles Greek (using Greek as a generic for incomprehensibility) meant criminal cant; a villain was one of St Giles’ breed or company and Francis Grose termed the breed ‘fat, ragged and saucy’; a St Giles buzzman was a pickpocket, but then so was a buzzman (playing on buzz, to ‘sting’) of any postcode. A St Giles carpet was a sprinkling of sand on the street: presumably to mask the latest bloodshed. Back slums, wherein Pierce Egan’s Tom, Jerry and Logic spent a merry evening pursuing Life in London among the cadgers, i.e. fake beggars, gave back slummers, defined as ‘dirty, common, low, and vagrant people’. (Slum originally meant a room, possible because it was a place to slumber). A blue boar, as the sexually imprudent called a venereal bubo, seems to have come from the generous girls of the Blue Boar tavern, sited on the corner of Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road, the southern boundary of the rookery.

There were other names than Holy Land: it could be Calmuck Tartary (though why, who could say; perhaps it seemed as alien as the Mongol Empire?) and Palestine in London which played on the ‘holy’ rather than on the usual Middle East-Jew link which in time would render Brighton as Jerusalem on Sea and Belgravia as Mesopotamia. To dine with St Giles and the Earl of Murray was to go without one’s dinner: the earl in question was buried in the churchyard.

Ned Ward, writing his Compleat and Humorous Account of All the Remarkable Clubs and Societies in 1709, introduced readers to the buttock ball, a local entertainment which ‘was begun, above thirty Years since, by a half-bred Dancing-Master, over the Cole-Yard Gateway into Drury-Lane; a Place so conveniently seated among Punks and Fidlers, that the Mungrel Undertaker was always sure of Musick, and equally certain of a Crowd of Whores to Dance to it.’ It seems to have been a precursor of the modern meat market, each one seeking a complaisant other, but Ward was more elegant, or at least elaborate, terming the ball both a ‘School of Venus’ and a ‘Diabolical Academy’; its regulars were ‘a mottl’d Diversity of Rakes, Beaus, grave Hypocrites, and Apprentices; Pimps, Bullies, Stallions, Valets, Butlers, and disguis’d Livery-Men; Thieves, Gamesters, Sweetners, Town Traps and Highwaymen; Procurers, Punks, Cooks, Jades and Chambermaids; damn’d filing Whores, sill Sows and Fireships; lewd Widows, wicked Wives and whorish Daughters; these Larded, by Chance, with here and there, a maid, but the fewest of that Sport of any.’ Did anyone, one has to ask, not attend?

Like Tom and Jerry Dickens – as Boz – visited St Giles but less tolerant than Egan, or more bound to the evangelical moralising of his time, he shuddered at the ‘filth and squalid misery’ but admitted to the excellence of its gin palaces, selling ‘The Cream of the Valley’, ‘The Out-and-Out’, ‘The No Mistake’, ‘The Good for Mixing’, ‘The Real Knock-Me-Down’, ‘The Regular Flare-Up’ and ‘a dozen other, equally inviting and wholesome liqueurs’. But by Dickens’ time St Giles was already suffering architectural assault: New Oxford Street was driven through in 1847, removing as it came the riper alleyways. That Mudie’s, the epitome of Victorian sanctimony, established its first lending library there is suitably ironic. Its reputation is slightly improved by the weekly appearance of the scholar Frederick Furnivall who recruited at the local ABC teashop for the rowing eight of shop-girls whom he coached on the Thames. While thus employed Furnivall did other things, among them founding the Oxford English Dictionary.

A very interesting picture, Jonathon, of the English welfare state, oh so long ago. The ever active Itie carries on his quest even today, having adorned that Parisian square with spirally wound ducting (rumour has it that it was he, not his gaffer, who was the shaking mover behind the design.) Pompidou added further to the Parisian pet lip when he ordered the flatpack kit from the Ruhr.

Renzo’s recent fettling of Köln’s Schildergasse, hurling at it copious amounts of glass and aluminum, generously sprinkled with Calatrava curves, has hammered down the final nail in that coffin, the one marked ‘here lies the artist’s street, died from urban mangling.’