Author and architecture expert Philip Wilkinson of the English Buildings Blog introduces us to the work of Stephen Bone, a mid-century illustrator who seem to have slipped unjustly from view.

I spend quite a lot of my life – whether I’m writing and researching English buildings or just staring out of the window of my house in the quintessentially English Cotswolds – sitting up and thinking of England. When I chanced upon a book called Albion: An Artist’s Britain, therefore, I couldn’t resist taking it from the shelf in the secondhand bookshop. And wasn’t there something familiar about the author’s name? Ah yes, Stephen Bone, the writer of one of the postwar Shell Guides to the British regions and counties that I’ve found so useful in the past.

Taking the book down, I discovered not just interesting reflections on Britain in the 1930s, but also a beautiful series of illustrations. The book fell open at the Norfolk farmyard scene, all steam and mist and frost and standing water. There isn’t much architectural content to fuel my interest in buildings (apart from the corner of a structure on the right, which looks as if it’s built of flint with brick quoins) but I greatly admired the way this painting of West Runton conjures up a place and a time.

Stephen Bone (1904–58) was the son of the Scottish artist Muirhead Bone (another reason the name was familiar) and his wife Gertrude Helena Dodd. He was encouraged to draw by his father and was taught as a boy by Stanley Spencer, who lodged for a while at the Bone family house near Petersfield. Bone went to the Slade, but left early, not liking the school’s academic approach to draftsmanship, and embarked on a career as a book illustrator, excelling as a wood engraver. He also travelled widely, notably with his wife and fellow artist Mary Adshead (they met at the Slade), and when he travelled, he painted, producing colourful landscapes on board. Some of these travels led to the book I discovered that day in the secondhand bookshop.

What a lot of atmosphere Bone conveys with his limited and rather muddy palette. It’s winter in West Runton, and quite early in the morning. The farm is already hard at work – the threshing machine is steaming away, someone is on top of a stack, a horse waits patiently between the shafts. We observe all this through the gate, at one remove, as it were – and through the mist, which makes the scene less distinct but also encourages us to look into the picture and puzzle at what’s going on. Bone reported:

‘Dimly through the mist one sees threshing in progress. The January frost was thawing into mud and my feet were cold and wet.’

From Bone’s thick, painterly way with the mud and frost in the foreground to the looming shapes of stacks and buildings in the distance, from the vague figures to the precise lines with which objects such as ladders and cartwheels are delineated, it’s clearly a composition that has been put together with great care. At first glance it all seems to so casual – those thick foreground daubs of paint. But look for a minute or two. Look at the gate, for example, and the artful way a few strokes of the brush summon up the shadows on the uprights, the frost on the top rail. Look too at the combination of diagonals (ladders, cart shafts, the stack-man’s fork handle), again portrayed with a few slender lines.

Bone worked similar magic in many other locations. In the top picture, Figures notated rapidly in a few blocks of colour each, play on the beach at Cromer against a background of hotels, houses, and a grey towered church. The sky is cloudy and I don’t think it’s too fanciful to imagine that those clouds were moving and that it was a windy day.

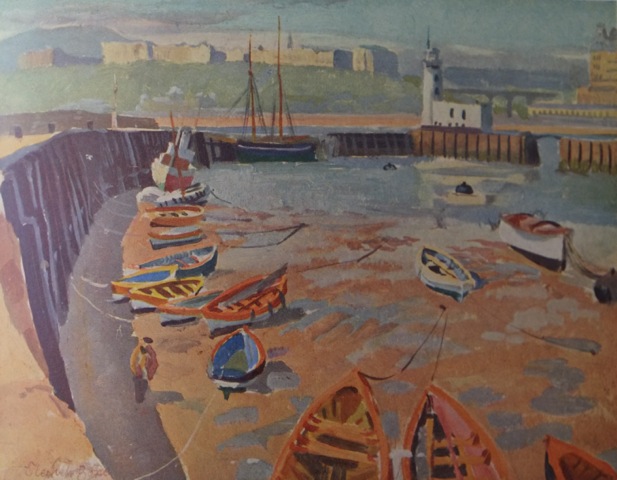

In another seaside scene, this time showing low tide at Scarborough, the artist allowed himself a bit more bright colour, in the blues, oranges, and yellows of small boats. Patches of water, many depicted in a single broad brushstroke, give them context. Grey town buildings loom on the horizon and the pavilion roof of one of the big hotels, the Grand perhaps, is just visible on the far right.

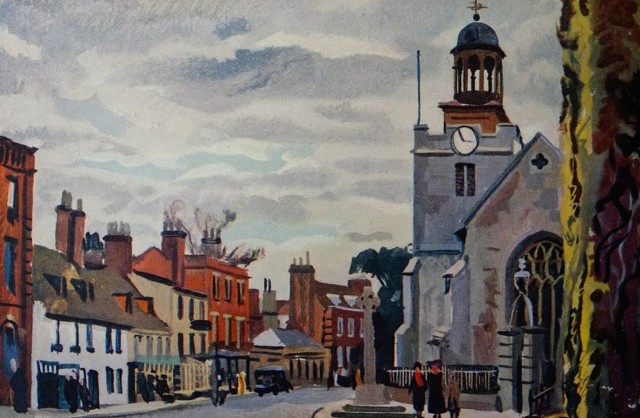

Stephen Bone had just as much fun with more workaday scenes, such as his evocation of the railway and backs of houses at Chalk Farm (more steam), and his study of brick and stone buildings in Lymington, again with a rapid brush but still bringing out details, from a quatrefoil window to a weather vane.

Bone’s Albion was published in 1939, the year war came. Its author-illustrator joined up, serving in the camouflage unit before becoming an official war artist (his father had been the very first official war artist in World War I). After the war he continued painting his landscapes, but dealers found them uncommercial. Bone carried on painting the way he wanted to anyway – but forged for himself additional careers in illustrated books (working with Mary Adshead), as a broadcaster (on popular British radio shows such as The Brains Trust), and as an art critic. I think he’s probably still rather under-appreciated: my copy of Albion cost just £5.