While the rest of the world thinks it’s Valentine’s Day, at The Dabbler we know that the real significance of today is that it marks the 250th anniversary of Percy’s Reliques. Prof Nick Groom explains how the seminal collection of ballads kickstarted the British folk tradition…

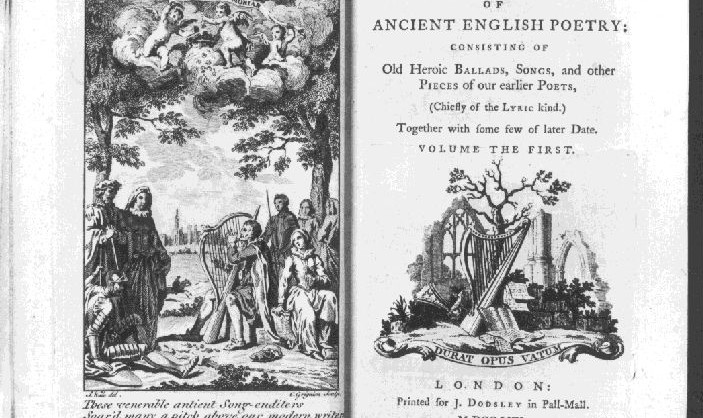

On 14 February 1765 – St Valentine’s Day two hundred and fifty years ago – a three-volume book with the title Reliques of Ancient English Poetry was published. It was the first serious collection of old English and Scottish popular ballads and, in a very real sense, marks the beginning of the folk revival in Britain; it also had profound effects on the emerging cult of Mediaevalism – the fascination with the architecture and literature of the Middle Ages which would develop into the Romanticism of the early nineteenth century – and inspired national folklore revivals across the whole of Europe, notably the German Volkslieder movement: the people’s culture.

Reliques of Ancient English Poetry was compiled by one Thomas Percy and so was popularly known as ‘Percy’s Reliques’. Percy was young clergyman living in Northamptonshire with a keen eye for the printing press. He wrote poetry and songs and fables, and was a dab hand at spotting literary trends – in the early 1760s he published a range of short handy books, from the first English translation of a Chinese novel (admittedly translated by Percy from the Portuguese rather than from Mandarin), a versification of ‘The Song of Songs’, and a collection of Viking poetry. This latter, which includes the chilling ‘Death Song of Regner Lodbrog’, could be seen as hopping on the ‘Ossianic’ bandwagon that James Macpherson had sent careering through the literary world in 1760.

Macpherson claimed to have discovered the lost works of the third-century Celtic bard, Ossian, in the Highlands of Scotland, including fragments of what he edited into two epic poems. Ossian, the ‘Scottish Homer’, thrilled the reading public with his haunting and heroic scenes of ancient warriors grimly facing battle, of their needless slaughter, and of the subsequent devastation of the Celtic civilization – although some, like the pugnacious Samuel Johnson, dismissed Macpherson’s discovery as an impudent literary forgery. Nevertheless, the enthusiasm for Ossian revealed that there was an appetite for mysterious British antiquity over the conventional taste for classical Roman literature.

Enter Percy. Percy not only had a keen eye for cultural fashions, but also a deep interest in the tradition of English poetry, particularly the works of Mediaeval and Tudor writers that were, at the time, decidedly out of favour. And among the early editions of Chaucer and Spenser that he had acquired at knock-down prices was a real rarity. One day, while visiting a friend in the country, he had noticed a maid lighting the fire with old paper – very old paper. She was, in fact, tearing waste paper from a manuscript book that dated back to the previous century and contained scores of old songs and ballads and romances, many of which seemed to derive far back in the mists of the Middle Ages. It was not unusual for old paper to be put to all sorts of domestic uses, from lining pie dishes to less salubrious purposes in the privy, but what was trash to the uneducated maid was the literary find of a lifetime for the young scholar. Percy asked for the papers, and so acquired what has since been known as the ‘Folio Manuscript’.

The discovery of enigmatic books and manuscripts has since become a staple of fiction – particularly the Gothic novel – and survives today in horror films such as The Blair Witch Project, which adapts the conceit to one of found documentary film footage. But Percy’s discovery was not an elaborate fabrication: the Folio Manuscript was genuine (and is now in the British Library). The upshot of this was that, after consulting the great Ossianic sceptic Johnson, Percy resolved to edit and publish the Folio Manuscript. After several years of labour, the Reliques appeared.

But of course, things are not quite so simple. When Percy’s Reliques was finally published, only about a quarter of the songs and ballads actually derived from the Folio Manuscript, despite Percy frequently invoking his source and indeed picturing it on his title-page. Instead, Percy had ransacked libraries and archives to corroborate and supplement his often patchy source materials, and neither was he averse to silently filling in any gaps there might be in the originals or replacing dubious readings with his own words, lines, and stanzas; unsurprisingly he also censored obscene material, although he did allow the darker verses of blood, revenge, madness, the supernatural, undead revenants, and even torture and cannibalism to remain.

He also provided erudite headnotes, essays, and introductions that outlined a Mediaeval culture based around the figure of the minstrel, the singer of traditional songs. Percy imagined minstrels to be at the centre of the court – guardians of lore and heritage; commemorators of contemporary deeds of valour and derring-do; and valued counsellors to kings. Accordingly, they typified the values of a sophisticated old English society that could be contrasted not only with classical Mediterranean culture, but which also offered an alternative to the primitive Scottish Ossian.

The upshot of Percy’s omnium gatherum of sources, his meddling with texts, and his admittedly fanciful context of chivalric minstrelsy was that the book electrified public taste. The Reliques was a runaway success and kick-started ballad and folklore collecting across Europe. Antiquarian scholars began to seek out and preserve songs, sayings, customs, and legends, connecting Britain with its mythical past and providing the next generation of writers and artists with a rich tradition of belief and superstition rooted in the indigenous past.

Percy was not the first ballad collector – Samuel Pepys had an extensive, if unpublished, collection; neither was the Reliques the first anthology of songs – earlier collections such as the delightfully titled Pills to Purge Melancholy had been popular in their day. But Percy’s Reliques was the first to demonstrate that songs and ballads were part of our national heritage, and thus deserved attention.

Without Percy’s Reliques there would be no ‘Rime of the Ancient Mariner’; it was the favourite book of Walter Scott and inspired him to salvage the Scottish ballad tradition; its influence can be felt in the Pre-Raphaelite visions of Arthurian knights and damsels in distress, and in today’s folk scene, which is rediscovering the legacy of Thomas Percy and his disciples.

Two hundred and fifty years on, the song remains the same.