From the Dabbler’s rich archives, Toby Ferris examines the place of teeth in the art of fifteenth century Italy and Northern Europe…

I have come to realise that if I am to make any real progress on my much anticipated, much delayed History of Whistling, I will first have to address the associated history of teeth.

I can do no more here than break a little ground, and think for a moment about teeth in art – specifically, the art of fifteenth century Italy and Northern Europe; for this is a world, seemingly, without teeth. The fifteenth century did not paint teeth, and I am forced to document, and speculatively account for, an absence (with a handful of telling exceptions, which I will come to).

It should be noticed first of all that the absence of teeth is not merely determined by whether mouths are painted open or closed, although there is a statistically significant predominance of closed mouths both in quattrocento and also Flemish art. Open mouths are represented as empty caverns, as though painters had no paradigm on which to draw and teeth were simply not in their repertoire.

How to explain this? In part, of course, it is just a question of the pose and its associated history – who could grin through a sitting? But it is a also matter, clearly, of decorum. The mouth parts are one of the portals to the inside of the body, the warm, clammy and damp interior. When Mikhail Bakhtin, discussing Rabelais and the carnivalesque, locates comedy in the ‘material bodily lower stratum’ – the stomach and digestive tract, the genitalia – he might have added that the mouth, the teeth and tongue, are the outermost precincts of this system. The teeth are an emblem of carnality, and to display them a contravention of decorum.

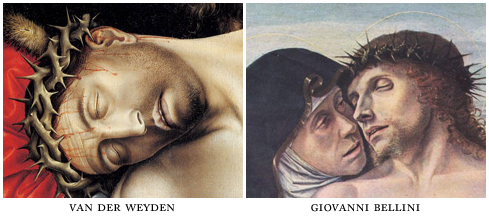

Which brings me to the exceptions. The damned in last judgements, wedded in life to their mortal flesh, have teeth, and they gnash them. So do all manner of animals and devils. So, of course, do skulls, teeth bared in death. And so, not strangely in all these connections, does the dead Christ, in paintings for example by van der Weyden and by Giovanni Bellini.

A dead Christ is an emblem of the fully incarnate god. To look on the face of a dead god is to see him as a man. And if Christ is fully man, then he must have a full set of teeth.

By the sixteenth century the gawping peasants who are finding their way on to panels and canvases also have teeth, plenty of them, wonky and yellow and gapped and hilarious, a trope anticipated by a very few Netherlandish paintings of the fifteenth century, such as the Portinari Altarpiece by Hugo van der Goes which so astonished Florence when it was displayed there in 1483.

And in fact, properly sensitised, if we look back at quattrocento art, we do find examples of painted teeth which do not fit the pattern of rule and exception, as though an arcane painterly language is being spoken which we are only now tuning in to, the subtleties of which we have not yet fully penetrated; as though our thoughts on carnality and death were in fact over-determined, and the concern of painters in fact lay elsewhere.

It comes as something of a shock, then, to switch to something from a more comfortably demotic age and culture, and see teeth painted with unabashed and uncryptic glee, as here by Frans Hals:

But this picture still falls, if my instinct is correct, fully within the accepted visual code of teeth. Bared teeth suggest carnality and death and this piece, like so much Dutch art of the seventeenth century, is about transience considered not as a boon of providence but as a mortal sadness.

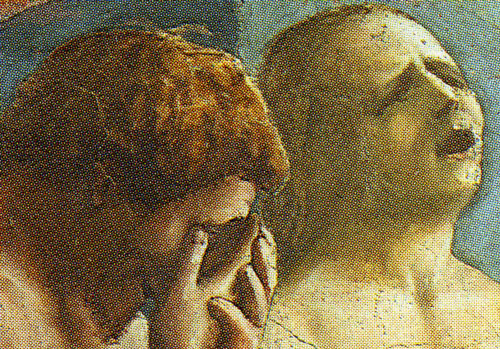

And, to come full circle, it is no more shocking, I think, than this:

This is Masaccio, of course, the great progenitor of the Florentine Renaissance, and these are Adam and Eve expelled from Paradise. In spite of whatever I may have said about the inherited decorum, about the general absence of represented teeth, in this case the absence is almost the focus of the painting; not so much because these individuals are so clearly ill-fitted for the rigours of the world, which is going to demand among other things a strong set of teeth; but rather because the absence of teeth suggests that coming thus abruptly into the mortal state is not a dispossession, but more like the taking possession of a ransacked house; and the only form of protest available is a speechless, voiceless grief.

The boys in the Schildergasse knew a thing or two about gnashers, especially when standing in front of a wooden panel, brush in one hand, yer book of revelations in the other. Where would Weltgericht be without the odd set or two of Hampsteads.