In his early 20s Douglas Dalrymple followed a romantic notion to work in a salmon cannery in Alaska. It turned out to be tough. Here is his story…

It’s a romantic notion. By way of explanation for a summer’s grubby employment on a steamer bound for Alaska in 1923, E.B. White breezily suggested that, after all, “there is a period near the beginning of every man’s life when he has little to cling to except his own unmanageable dream.” In fact, White had just been dismissed from his job at The Seattle Times, had no real prospects, and would otherwise soon be homeless. But romantic notions are often well-timed. In 1996 I was about the same age as White had been, and in similar circumstances, when I made my own trek north for a job at a salmon cannery in Ketchikan, Alaska. No doubt there was something dreamy in the expectation of it. ‘Nightmarish’ might have been a better word for the actual experience. But as dreams go it didn’t seem so unmanageable at the time.

I had originally been scheduled to start later in the season but the fish showed up earlier than expected, so I cut short a visit with family and flew out from San Francisco. Above Vancouver Island and British Columbia the world was a Pollock canvas of lowland clear-cuts, mountain spires and snaking glaciers, the view vast and unencumbered. Then somewhere near the Queen Charlotte Islands the weather blackened below and we began a wet, blind descent to Ketchikan through winds that might have flipped our plane like a paper glider into the sea. The landing was rough, but not so rough as the ferry crossing from Gravina Island, where the airstrip is located, to the larger island of Revillagigedo where Ketchikan squats at the water’s edge. This is the passage which Sarah Palin’s infamous ‘Bridge to Nowhere’ would have spanned, and I can tell you that not a few motion-sick travelers would have been happy to find it there.

Ketchikan occupies a strip of shore at the southwest corner of Revillagigedo, which is otherwise an empty wilderness of rocky little mountains and temperate rain forest. White called Ketchikan a ‘mosquitoey place, smelling of fish,’ which would be accurate except that it rains so much the bugs are often grounded. It does smell of fish – and the stink only gets stronger as you approach the canneries at the south end of town. Once inside the cannery I found the smell so astonishingly pungent I spent the first three days struggling to keep my gag reflex in check.

Just as overwhelming was the sound. The volume inside the cannery was such that if your ear protection was jostled loose your other senses were temporarily disabled by a sort of sympathetic shock: hands would hang limply at your sides or flap about, knees would buckle, eyes blink uncontrollably. As a cannery worker, you learned to do without verbal forms communication. Before and after your shift you were aware of possessing broader powers, but on the job you were a deaf mute and communicated by means of gestures and symbols, notes written on scraps of cardboard, or by alphabetic sign language, which is quickly learned but slow to the purpose of carrying on a conversation.

Most employees lived in the bunkhouse on cannery property and dined (all to often on salmon) at the cafeteria. Many were college students from the ‘Lower 48,’ though there were also a number of Filipinos and Mexicans, whole families in fact, and a handful of aging hippies who returned every summer and spent the rest of the year in Thailand or India, living cheaply off their cannery wages. Alaskan salmon canneries tend to hire non-Alaskans, a fact sometimes resented by the locals, but the two or three Ketchikan residents hired in ‘96 each quit after a week or two. It wasn’t the sort of job you were willing to keep if you had any other options whatsoever. College students and foreign families stayed on because they really needed the money or had nowhere else to go.

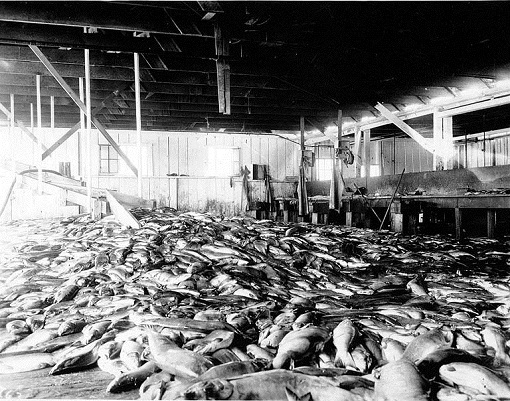

I spent most of the season as an ‘end-feeder’ at the tail of the production line, inspecting can lids and loading them into a machine that clamped them onto tins of raw fish. At the other end of the line the catch was vacuumed from the hulls of docked vessels into giant holding tanks in a section of the cannery called the fish house. There salmon were cleaned by a machine that scooped out their entrails, cut off their heads, and clipped most of their fins. They were then were run through a gauntlet of knife-wielding fish house employees who took care of any loose bits. The cleaned fish were next shuttled down a belt that split into separate lines before being chunked and stuffed by machine into open tins sent down from the can loft. The filled cans were weighed and adjusted as necessary by workers on the ‘patch line’ and then fed down the belt to me and my machine. After passing me, the lidded cans were trundled into giant pressure cookers and prepped for shipment.

The most unpleasant jobs in the cannery were those in the fish house or on the patch line since they required standing hunched over a table all day. In fact, I started out on the patch line. After a week of it my back and neck were painfully seized up, due in part to the nature of the work and in part to an automobile accident I had been in the year before. I chomped down ibuprofen tablets like they were breath mints. Each of my breaks I spent flat on my back on the bunk house floor while the muscles along my lower spine cramped up like bridge cables. One of my coworkers, a forty-something hippie who was always chattering about Krishna, taught me a couple yoga positions, but relief was minimal and brief. Slowly, shamefully, I realized I would have to quit and lope back south with my tail between my legs. But thanks to the influence of a friend who’d built up some seniority over the course of four summers, I was mercifully offered the job of end feeder when it unexpectedly opened.

The end feeder’s job was, in fact, one of the more desirable in the cannery. I had a stool on which to sit, which saved my back. From my post at the end of the line I inspected over 100,000 can lids a day, flipping through them like cards to look for imperfections. After loading the feeder full I had about 45 seconds of free time before I had to load another row to keep the machine running. This allowed me to carry on sign language conversations with end feeders on other lines or with my friend peering down from the can loft. It also gave me mental leisure enough to minutely reconstruct the scripts of dozens of Seinfeld episodes and the lyrics of every Beatles song I’d ever heard. I found that by unhurried concentration I was even able to flesh out the vaguest childhood memories. All the details of one’s life, I realized, were stored somewhere in the brain and could be gently coaxed into the light again if only one wasn’t in much of a hurry. All you needed was time.

And at the cannery we all had plenty of time. A typical shift would start about 7:30am and end about 11:30pm – or as late as 1:00am if you were assigned to the clean-up crew that night. We each worked in excess of 100 hours per week, with no weekends and no days off unless the fish just weren’t there and the boats had come back empty from their three-day openers, which only happened near the end of the season. Overtime was mandatory (to the tune of sixty hours each week). Most days you felt like you’d signed yourself up for a labor camp.

Despite the long hours, or maybe because of them, few of us were ever in the mood for sleep at quitting time. There was a bar (The Potlatch) within walking distance, but it closed early. We occasionally trudged up to the city dump for a bonfire, but the island bears were fond of the spot too. Most nights we simply made a tour of the bunkhouse halls, pressing through clouds of marijuana smoke to joke and jabber with friends over long swigs of Jim Beam while someone played a guitar or banjo. We would compare the growth of our beards, trade reading materials and music, catch up on national politics and family news, and pass around the latest cannery gossip. There were, of course, the standard personality conflicts and romances. There were casualties, too. That summer a couple digits were lost and one poor fellow’s arm was sucked into the big machine in the fish house and shredded below the elbow (he was airlifted 800 miles to Seattle for emergency surgery). When we finally gave in to exhaustion at two or three in the morning, we dreamt only of salmon flesh and the mechanical roar of the cannery. At the alarm next morning my roommate and I would mimic the sounds of bombs whistling and concussing in an attempt to express our dread of what lay before us again.

On the rare occasion that we had a free hour of daylight we would explore Creek Street and downtown and laugh at the tourists pouring off the cruise ships. These kept mainly to a well-groomed three or four block area of kitsch shops and would-be trading posts announcing the frontier spirit in big, loud letters: “FURS! GOLD! IVORY!” In fact, most of these sold sweatshirts and baseball caps printed with totem poles and leaping salmon. The tourists were ignorant, innocent; they never saw the real Alaska – the one that we knew. They didn’t know the Alaska where day-hikers wandered off the trail and were never heard from again and never looked for, where eagles swooped down from the sky and made off with pet cats and family dogs, and where operators of more isolated canneries farther north scoffed at labor laws and threatened sick or injured workers with abandonment in the wilderness to keep them on the production line.

Once I saw an elderly tourist couple who had wandered farther than usual from the shopping district. They’d come to a little bridge over a creek so full of spawning salmon one could almost walk across their red humped backs. The retirees were clearly enchanted, snapping photos and smiling – until they came near a local boy on the bridge who hooked a fish and yanked it onto the narrow walkway in front of them and commenced to violently murder it with a metal bat. Blood spattered all over the walkway, over the boy’s face (he barely noticed), and over the elderly woman’s white clothes. She exploded into tears, shaking and covering her eyes. Her husband quickly turned her around and led her back to their cruise ship. I was asked to repeat this story again and again in the cafeteria for several days. Oh, the schadenfreude!

Toward mid-summer the long mind-numbing hours, excessive living, and lack of sleep began to tell on each of us. We looked and felt – and smelled – like hell. There was a physical toll in lost weight, sluggishness, and persistent chills and cough. There was a psychological toll too. It was two or three weeks before the end of the season when I began to hallucinate. On several occasions I thought I saw a large German shepherd loose on the cannery floor. Several times from the corner of my eyes I saw a dark hooded figure approach, waving his hands, only to vanish when I turned to see who it was. And on the way to my work station one day I froze in amazement when one of our union machinists passed by holding what looked like an enormous white gull or albatross with its wings spread out in front of him. Blinking, I saw that it wasn’t a bird at all but a large glue gun.

I heard voices too. Over the noise of the cannery and through my earplugs and muffs I heard the sound of a woman singing. I had to ask around before I could believe that no one else heard it. She had a low, smoky voice. The songs were familiar, though I could never quite name them. One day I stepped onto the cannery floor and burst out laughing when I heard her scatting. She was actually quite good and I enjoyed it for a while, but after several days of her cool scatting I’d had enough and began to fret for my sanity. I would have been more seriously concerned except that so many of my coworkers were complaining of their own hallucinations. It was sleep deprivation, I told myself, and nothing that wouldn’t come right in the end.

The fish were by now fewer and less healthy, the meat increasingly full of parasites. The salmon life cycle ends after spawning time and those late returning to their native waters tend to show up in poor shape. Accustomed to the clean, supple flesh of the pink and the coho and the incomparable marbled sockeye salmon we’d canned earlier in the season, we were revolted by the yellow, grainy stuff we processed those final days. This, we were told, was sold at discount to the military and to old folks’ homes. Passing through our hands it ceased to be fish at all and in our imaginations became something truly foul, unholy, an unspeakable substance like the half rotten flesh of aliens, or of humans. The job was becoming unbearable. But finally the season was called, all the workers were paid, and we were officially released.

We spent a day exulting in our freedom, slapping each other on the back and drinking toasts. Then we camped out at the Alaska State Ferries terminal to wait for the next boat south. When it docked we ran with our backpacks to a deck near the stern that was partially covered with heat lamps but open to the air on three sides. I took possession of a reclining deck chair, wrapped myself in my goose down sleeping bag and swore not to rise again till docking in Washington State. For us cannery workers the ferry became a floating sanatorium by day, and by night a city of light and laughter passing through the abyssal wilderness dark. The two day cruise down the Inside Passage, through orca highways and forest archipelagoes, was a feast of ocean air, northern summer light, and blessed sleep. The sounds, smells and sights that had infected both dreams and waking hours at the cannery fell away. All our hallucinations, exhaustion and hunger evaporated, and very soon, we knew, we would be well again.

In fact, my own recovery took longer than expected. I rode a hippie bus south from Seattle to San Francisco with my friend from the can loft. We stayed with my family for several days, planning a road-trip that would take us to Denver before returning to Seattle, where we would find an apartment together. While delaying in California, my parents discovered that I had changed. To them I was like someone locked in a dream, a survivor of an ordeal that had rendered him incomprehensible to those he’d left behind. Which is precisely how I felt. At twenty-three, romantic notions are slowly metabolized, and despite all its horror-film details I wasn’t over my unmanageable dream yet. I was still living it. Sometimes, like E.B. White who only committed his summer of 1923 to print decades later, I catch myself living it still.

I am really glad the comments are working again because I wanted to say what a great read this was! I can’t stand the smell of fish, so reading this was akin to reading a horror story – I felt queasy just imagining it.

Douglas, a terrific account. It’s wonderfully written and totally absorbing from beginning to end.