Jonathon Green introduces a 16th century printer and ‘compiler of cant’ who arguably produced the very first dictionary of slang…

Bokes be not set by: there tymes is past, I gesse;

The dyse and cardes, in drynkynge wyne and ale,

Tables, cayles[1], and balles, they be now sette a sale

Men lete theyr chyldren use all such harlotry

That byenge of bokes they utterly deny.Robert Copland, in Prologue to Henry Pepwell Castell of Pleasure (1518)

Nothing new beneath the sun, eh? Printing was barely coming up to speed and one of its leading practitioners, ‘the oldest printer in London’ no less, was holding forth and already towels were hitting the canvas. And forget my plaints as regard dictionaries and their parlous future. For this is Robert Copland whose own work, at least as lexicography’s canon runs, was not just a slang dictionary, but the very first.

Well, perhaps not the first – the concept of the ‘beggar-book’ with its descriptions of criminal vagabonds and an appendant glossary of their jargon, was well entrenched in Europe, and Copland’s brief work was hardly a dictionary, more a long poem into which are interspersed the occasional nuggets of 16th century cant – but absent alternative sources, this is what we have.

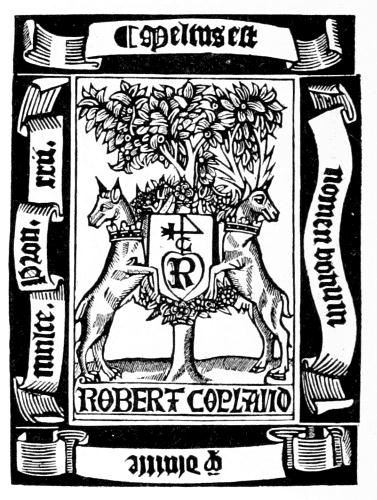

Like the language at which he briefly paused, we know very little of the man. (In this too he presupposes the biographies of all too many of his successors in the field). Even his birth-date remains a mystery, but his known professional career as a printer, bookseller and stationer, as well as a collector of cant, covers the years 1508-47 (when he seems to have died). He worked primarily as an assistant to the printer Wynkyn de Worde (d. 1535) who had in turn been William Caxton’s principle assistant from 1476. Copland claimed to have worked for Caxton too, but given their respective dates, this relationship is more likely figurative than factual.

Nor do we have a precise date for the book: it seems to have been composed at some time between 1529-34 and probably published in 1535. The title we do know: Hye Waye to the Spytell-Hous which can be loosely translated as ‘The Road to the Charity Clinic’; a spytell house, synonymous with a lazar house or poor hospital, was a form of charity foundation, dealing specifically with the poor and indigent and especially with those suffering from a variety of foul diseases.

The Hye Waye is a protracted verse dialogue, supposedly conducted between Copland and the Spytell House Porter. The clinic in question, while un-named by Copland, is generally accepted to have been St Bartholemew’s Hospital, London’s oldest, founded in 1123 near the open space known as Smithfield, once witness to burning martyrs, to the guignol excesses of Bartholomew Fair and latterly London’s central meat market.[2] Trapped in the hospital porch by a snow storm, Copland strikes up a conversation with the Porter, taking as their subject the crowd of beggars who besiege the Spytell House: ‘Scabby and scurvy, pock-eaten flesh and rind / Lousy and scald, and peeléd like an apes / With scantly a rag for to cover their shapes, / Breechless, barefooted, all stinking with dirt.’ The pair then discuss why some are allowed in and others rejected. Copland notes and the Porter describes the various categories of beggars and thieves, as well as the tricks and frauds that are their stock in trade. They further note the way folly and vice lead inevitably to poverty and thence disease and finally, willy-nilly, to the Spytell House.

The Hye Way falls into two halves, the first focussing on beggars, the second on fools. Whatever the source of the ‘criminological’ verses, the second half would appear to have been influenced by Robert de Balzac, one of the minor French writers whose work Copland would have known, and author of Le chemin de l’ospital (The Road to the Hospital, 1502). De Balzac’s catalogue of fools does not deal in crime, but it undoubtedly gave the English author his title.

The Hye Way does not offer a separate ‘canting vocabulary’, but it does provide vivid descriptions of a wide range of what would be known as ‘the canting crew’, ‘diddering and doddering, leaning on their staves, / Saying “Good master, for your mother’s blessing, / Give us a halfpenny’. Some, explains the Porter, are justified in their beggary. Others are not.

By day on stilts or Stooping on crutches

And so dissimule as false loitering flowches,

With bloody clouts all about their leg,

And placers on their skin when they go beg.

Some counterfeit lepry, and other some

Put soap in their mouth to make it scum,

And fall down as Saint Cornelys’ evil.

These deceits they use worse than any devil;

And when they be in their own company,

They be as whole as either you or I.

There are false scholars, and quack doctors, and, inevitably, corrupt clergy, posing as Pardoners. There are those who claim to have escaped French prisons. Once enough money has been earned, explains the Porter, all such ‘nightingales of Newgate’, repair to brothels and taverns, dressing up in far from ragged finery and making ‘gaudy cheer’.

The text includes 51 examples of cant, here, in only its second printed use, called pedlar’s French. Among them are apple squire, a pimp; bouse, alcohol and bousy drunken; callet, a whore; cove, a man; darkmans, the night; dell, a young female tramp, still perhaps a virgin but seen as an embryonic whore; dock, to have sex, especially to deflower; gan, the mouth; instrument, the penis; jere, excrement; lift, to steal; make a halfpenny; nab-cheat, a hat; nase, drunken; nug, to enjoy sexual foreplay; patrico, a priest, or wandering beggar posing as one; peck, to eat; poke, a wallet or purse; poll, to rob by trickery rather than violence; prancer, a horse-thief; ruffler, a villain, of the ‘first rank of canters’, who posed as a discharged soldier though equally likely might have been a former servant; tour, to spy on and win, a penny.

[1] I am defeated by this. The OED has it only as a variant spelling of kale, cabbage. Given its companions a foodstuff seems anomalous here. I grasp at the MED’s calewei, a kind of pear, but remain unconvinced.

[2] but not for long; it is due to close in 2014 and doubtless some architectural Godzilla is even now poring over the plans for its destruction, or worse still, ‘development’. The words ‘piazza’, ‘heritage’ and ‘viable use’ are bruited loud.

Is that the very first complaint of the death of books, do you suppose? Or did Caxton himself despair at the end of his first shift?