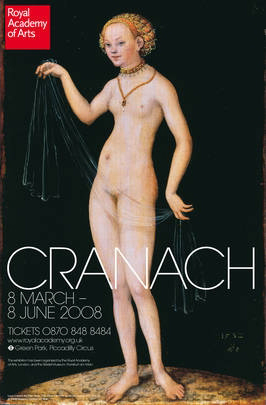

Lost in reproduction: a tiny Venus meets a colossal Samson.

I was recently in Frankfurt for a few hours and visited the Städel gallery, where I reacquainted myself with Lucas Cranach’s Venus (1532), the painting used as the poster image for the Royal Academy Cranach show of 2008.

She is an unforgettable creation, a lightly-modelled snaky gothic lady with a diaphanous and entirely fictitious veil, standing on a heap of lunar rubble.

The poster hangs on a wall in a corner of my house. I have, over the years, spent a lot of time looking at it, thinking about late Northern Gothic, and other things. The poster is, needless to say but also crucially, poster-sized; however, I never thought in all this time to check the dimensions of the painting itself. I was knocked back, therefore, to discover (or rediscover) in the Städel that the panel is only 37.4 by 24.5 cm. Venus is just a few inches high; you are forced to bend in and inspect her, pruriently, as though she were a homunculus summoned in a bottle.

She hangs, moreover, in a corner of a vast room of large compositions – other Cranachs and Dürers and Holbeins, and I don’t recall what else. And through the door at the end, I think I remember, you can see Rembrandt’s Blinding of Samson (1636).

The Rembrandt, in contrast with the Cranach, is a colossal composition, not just in size (206 x 302cm) but in manner – the paint is slapped on in violent gouts and streaks and approximate dollops (in particular on the highlights on the armour and manicles, and on Delilah’s pearls and skirt); both the vividness and vigour of the painting, you begin to understand, and the acuteness of the depicted light penetrating the chamber, do not so much re-enact the violence of the scene, as oppose it: the blinding is realised as a bacchanal of clear and visceral seeing, and the protest would not be so impassioned on a diminished scale.

Size and meaning are intimately linked. Or perhaps meaning is the wrong word. Size is linked to what a painting does. Rothko knew this – he painted radioactive fields of colour big enough to blot out all other visual stimuli, so that you are perceptually aswim in the vast implied non-space – but so did generations of miniaturists and illuminators, who counter-intuitively multiplied detail at the microscopical level at which they worked, so that the eye is anchored to increasingly, insanely, tiny things.

Partly for this reason, none of the Rembrandt’s visceral power is available in reproduction. You have to stand in front of it. But the same is true of the Cranach. Its scale and proportion are a crucial part of what it means – it an intimate, almost devotional object, originally forming a contrastive pendent (probably) with a similar painting of Lucretia; it is a meditative binary system. The manner in which you approach it is very different from the manner in which you approach the Rembrandt.

Reproductions aid memory in many ways, but they do not aid and can in fact confuse memory of scale. We hold our images in a universal card-file index of various standardised sizes – thumbnails, postcards, wallpaper, posters, and so on, and make them available online in high resolutions; but they remain no more than two-dimensional maps of a landscape you once visited, or might one day visit.

Going to see the image doesn’t help much. When you stand in front of a painting, you are unanchored, at large on the ocean of real experience. You move about, you move backwards and forwards, side to side, in and out, from various angles. There is no straightforward procedure for viewing it, as there is with listening to music or reading a book. You are just pitched into the middle of the object and left to paddle or flail about. You will never be able to take a series of calibrated mental snapshots of the object in question; as with most experience in life, you do not really know what it is you are storing up.

In short, presence offers us a certain sort of knowing; memory, quite another. Unfortunately the world -whether of paintings or otherwise – is characterised for us mostly by absence; it is a closed cupboard of concepts and things and people which we can access voluntarily, but never in their entirety, never all at once. And of course, in that cupboard, the objects of memory fade, change, distort, etiolate, as memory plays on one aspect rather than another – we remember the content of a painting, the figures, some anecdote surrounding our visit to it; we recall it to our mind’s eye, but it is hazy, blurry, inaccurate; and one thing we never remember correctly is its size.

Thank you Toby, for helping me, in your penultimate paragraph, to understand that which Rudolph Otto called the ‘mysterium tremendum’ – something, in a way, that can never be understood – the infinity of God on the highest level or, closer to earth, the miracle of a Rembrandt self portrait or just a phrase of Mozart. Books and music are ‘linear’ and have a beginning, middle and end. Paintings are just ‘there’ and I’ve never been quite sure how to deal with a great picture, or even with a bad one. How do I know it’s bad? Oh, I must have read it somewhere. Did somebody once suggest that the ‘best pictures are not always good pictures’?

No, I’m never too sure either. It is complicated of course by the fact that paintings often have a narrative content (would it be odd to begin looking at the Rembrandt by concentrating on the rendering of certain surfaces? Probably, a bit). So I suppose that is where you loosely ‘begin’ – but I often have a sense of needing to settle in front of a painting; and sometimes I realise after five minutes looking at something that I have no idea what the painting is in fact of. I also end up never looking at the things I think I’m going to look at. I was in Vienna not so long ago where the Vermeer Art of Painting is, and I stood in front of it for ages, but spent most of the time wondering about the relative hues of blue, and whether one in particular was in fact green, without reaching any sort of conclusion. I was surprised, incidentally, by how big it was; which means the next time I see it I’ll be surprised by how small it is.

Perhaps its all a bit of misdirection, as you hint – trying to get a sense of the invisible, the unpaintable, out of the corner of your eye, by thinking about some inconsequential detail. There’s a good essay on precisely that by Daniel Arasse – about the snail in an annunciation by Francesco del Cossa:

http://intranslation.brooklynrail.org/french/the-Snail%E2%80%99s-gaze

What a superb and thought-provoking post. Two of my favourite paintings in the National Gallery are surprising in terms of their real-life size – Seurat’s Bathers at Asniers (big) and Van Eyck’s Arnolfini portrait (teeny). Your post casts light on the reasons why.

Thanks Brit – yes, van Eyck is another whose paintings are always smaller than you remember – the Chancellor Rolin in the Louvre is tiny as well, and the Canon van der Paele is always half the size I think it is. Perhaps it’s that childish thing of assigning things size according to their relative importance. Don’t know how it would work the other way around, however, with the Seurat for example.

On a possibly unrelated note, I was staggered to discover (on the BBC4 documentary that was on a day or two ago) that an African elephant is much bigger that a woolly mammoth ever was.

Perhaps its just a general deficiency on my part – all my relative scales are wrong since childhood. I’d probably be disappointed if I saw a blue whale.

Sono impressionato dalla qualita’ delle informazioni su questo sito. Ci sono un sacco di buone risorse qui. Sono sicuro che visitero’ di nuovo il vostro blog molto presto.