If we listen at the tombs of the ancients what can we hear?

In the suburbs of the small town of Tarquinia in Northern Lazio there is a necropolis of the former Etruscan inhabitants. Etruscan necropolises vary in form depending on local custom, rock-type, age and so on. The necropolis at Cerveteri, for instance, is built to the plan of a city, with streets of monumental tombs in the form of round huts and terrace fronts, mirroring the town of the living.

The Necropolis of Tarquinia, by contast, is an inverted city of the dead: single or multiple chambers are cut into the soft volcanic tufo rock and surmounted with tumuli; all that is visible of them so many hummocks on the level hillcrest, with their various concrete entry-ports.

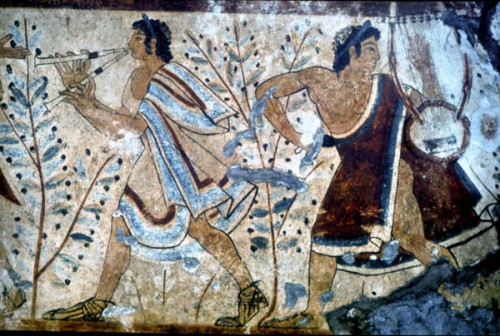

The walls of roughly two hundred of these Tarquinian tombs are painted with scenes of hunting and fishing, banqueting, orgies, games and swimming, dancing, music. According to D.H. Lawrence, who, shortly before his own death, viewed the tombs by acetylene lamp ‘death, to the Etruscans, was a pleasant continuance of life, with jewels and wine and flutes playing for the dance.’

While the painting is both extraordinary and famous, Tarquinia is sufficiently out of the way that, on a weekday morning in February, say, there will be no one but you and a guard or two up there on the windy hill top.

The chambers are approached down steep passages, now cut with steps. You sit on the bottom step of a given tomb, the air heavy and musty and immobile, peering through the toughened glass that seals off the chamber, looking at these vivid scenes, and you rapidly become aware of the peculiar sensory profile of the experience; in particular, the odd acoustical properties of the tombs. The tombs are humid and still, but above all they are silent.

There is, as I recall, a very low hum of electrical circuitry – lights, which come on automatically as you approach, and dehumidifiers. There is the sound of your breathing, disconcertingly loud; and of your booming voice if you happen to speak. Other than that your ear drums are left to grope in the aural darkness.

There is a branch of archaeology called archaeoacoustics, which occupies itself with the aural world of antiquity. It is a minor branch, given that archaeology typically entertains itself with the material culture, but I like to suppose that it is actuated by important questions such as, did the armies of Alexander whistle as they marched? Or indeed, did the ancients whistle tunes at all?

One of the early stimuli in the field of archaeoacoustics was the claim made by Richard G. Woodbridge III in 1969, in an article in Proceedings of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers which referred to some subsequently unverified and unrepeated experimental success, that sounds of ancient life might have been encoded in artefacts such as pottery, through vibrations transmitted by the hands of the potter; or in the plaster of walls by plasterers. We might, with adequate technology, reconstitute the voice of Masaccio’s workmen, or the workshop chatter of Exekias, or, less ambitiously, the sound of a dog barking, or someone whistling.

In truth, it is much more likely that sounds are not accidentally encoded in this way. Recording to a soft medium demands a refinement of the means of inscription, in order both to amplify and clean the input – requires, in other words, proper technology and intent.

This not only makes me a little sad – most of what we do in life is, so to speak, a whistling of the spirit; it is not etched into the world, so much as vaguely doodled with a mental finger in the warm muddy canals of the brain – but also has implications for my magnum opus, the history of whistling, which seeks in part to recover what cannot ordinarily be recovered – the sound of ancient worlds.

In the tomb of the Leopards in Tarquinia, there is a pair of musicians, one playing a lyre and the other a double flute.

‘Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard/ are sweeter’ says Keats, musing on the acoustical properties of a Greek pot. Perhaps only to the more empirical mind, then, does the active, almost aggressive silence of the tombs at Tarquinia, seem disturbing. Tombs are meant to be quiet, of course, but in that silent dance with flute and lyre, in that most aurally undifferentiated of places, we are acutely aware that a whole dataset is now irrecoverable. All the soft matter of life, including, not incidentally, that of the tombs’ former inhabitants, and their whole intricate civilisation, has been entirely erased.

And who can say that this is not how the Etruscans represented death to themselves: as a silent town, as flutes played in a vacuum, as tantalising grapes; an exclusively visual world, then, unsupported by any sense of taste, smell or touch. Or hearing. Perhaps what they painted was not life-in-death, as D.H. Lawrence surmises, but life shorn of complex sensory interaction and dimension. A life, so to speak, unwhistled.

Fascinating Toby! Rather mundane I know but I have seen an episode of Mythbusters on the Discovery Channel where they attempt to transfer sound into a pot as it’s made and then play it back. They tried many different approaches but came to the conclusion that it whilst it is possible to do using modern equipment it wouldn’t have been possible to do way back then! Very interesting though!

Thanks Worm – in my extensive ‘research’ I read something about the mythbusters episode on Wikipedia, but I haven’t seen it. I think the whole idea was more poetic than plausible, although as I say Woodbridge III did say he had experimental proof – he claimed to have encoded the word ‘blue’ in a pot, and one or two other things.

Fascinating indeed. Incidentally, it seems that Sarah Dunant is an Atlas of Norbiton reader as she’s ripped off your last bulletin about teeth and art something rotten for the BBC.

Frankly, I’m shocked and disillusioned. She didn’t even steal the best bits.

I wonder what was the first reference to whistling in literature – does anyone whistle in Homer?

I’ve asked myself the same question, without bothering to check, of course. I think we have to distinguish, very crudely, between palatial whistling (that used by shepherds and marriners) and puckered whistling (for a tune). I wouldn’t be all that surprised to find a shepherd whistling in Gilgamesh or the Bible, but I woud be surprised to find him whistling Colonel Bogey, if you see what I mean.

A dusty street in the land of the Israelites in a galaxy far far away, on an unspecified day between BC and AD…………

If life seems jolly rotten there’s something you’ve forgotten

And that’s to laugh and smile and dance and sing

When you’re feeling in the dumps don’t be silly chumps

Just purse your lips and whistle, that’s the thing

And always look on the bright side of life.

Incorrect answer allowed on programme of Monday 1st October- the last stage in the digestion of food is Egestion, but Excretion was allowed which is a totally different process involving the kidneys and bladder, and Victoria allowed this as the answer! It made no difference to the outcome of the contest, but I do like accuracy, as i think does Victoria.