Toby Ferris considers the significance of the physical act of writing, from scratching with an old nibbed pen to double-thumbing on tiny virtual keypads.

I still occasionally write with a pen – as the draft of this post will bear witness:

Writing with a pen is not just a minor feat of dexterity and an aesthetic pleasure in its own right; it is one of the marks of civility, something that places the literary life of Norbiton in a direct if admittedly distant cultural line with, say, Cicero and Saint Augustine.

But it is many years since I have written by hand extensively or as a matter of course. I now write, like everybody else I know, on a keyboard, an activity not without its own tactile appeal. And, while it might not connect us with Cicero, it does propel our spirits back into those hectic twentieth-century newsrooms, or to the journalist-literati banging out their taut prose, the Hemingways and Orwells. If the fountain pen is a melancholy device, typing is heir to a certain literary energy.

It should nevertheless have died with the typewriter. It is one of the strange emergences of our digital age that manual typing, once an arcane specialism, is now a routine life-skill, even if, unlike the decisive four-squareness of the typewriter proper with its resistance to correction or second thoughts, the keyboard now gives access to limpid surfaces of mobile floating text.

But I suspect that this sudden refluorescence of typing heralds its imminent and final collapse. A friend of mine, a computer scientist of eschatological habits of mind, is worried that a generation is set to grow up without keyboard skills of any sort, accustomed as it is to touchscreen technologies. This generation will necessarily be lost to computer science, which will remain, he argues, a practice founded on solid keyboard inputs. A keyboard, for all that it appears a clattering mechanical relic, is a highly particularised and adapted form of writing technology. You cannot realistically be expected to write code, with its complex litter of punctuation and patterns of indentation and so on, by swiping a smeary, variously responsive slab of glass.

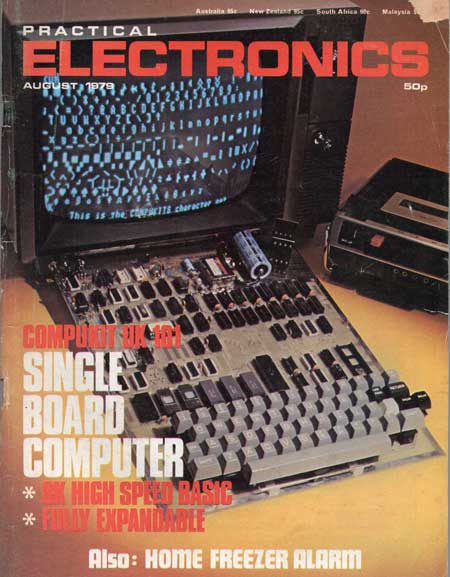

This friend of mine grew up in the early days of personal computing, the days of the ZX80 and BBC Micro. It was a time when using a computer was synonymous with writing code. And, while we should all no doubt be encouraged by the successful debut of the Raspberry Pi (released last week and sold out within an hour) which seeks to recapture some of that pioneering excitement, it remains true that programming a rudimentary personal computer in the early 1980s had a tang of the future about it, something which the Pi will find impossible to replicate.

In the Renaissance it was a commonplace that Creation was a legible form inscribed on the face of the earth, a grammar and syntax of sympathies and analogies and similitudes. To write in those circumstances was to participate at some level in the structuring of the universe. And the scientific revolution only upheld the validity of the metaphor – nature, or the cosmos, is not a random heap of stuff; it can be reduced to a coded form, whether the code is written in proteins or mathematical constants or, more latterly, in C++ and Linux.

Code not only describes the fundamental structure of the world we inhabit: it is now an extensive part of it. At its best (a level which, like all writing, it rarely aspires to, let alone touches) it is a distinct mode of thinking – again, like good writing – which not only reflects The World as found, but subtly and imperceptibly alters the code in which The World is written.

My friend, as I say, has eschatological habits of mind which I do not share. The fact that we cannot imagine a future without keyboards, or indeed writing, does not preclude that future’s arrival, nor our own adaptation to it. Perhaps we will redevelop our oral proficiency, coding by means of rhetorical mnemonics, supported by flawless voice recognition. Perhaps the computers will interface directly with ports in our heads (other than our eyes), flicker along merrily at the speed of thought.

Or perhaps – a stranger thought still – at some future point Writer and Programmer will merge, so that the only writing still done will be done in code, literature ceasing to be a sub-set of the entertainment industry and reasserting its hieratic credentials, its privileged access to the World’s Arcanum. Such a priestly, scribal caste might still then permit itself the use of ancient technologies such as keyboards and pen and ink, accessing the code of the cosmos with dead languages (Fortran, C++, Java) and their pseudo-cuniform scripts.

Well, perhaps not. But such a remote and rarefied literary culture would conform to known paradigms in one important way: it would root literary and aesthetic and spiritual and intellectual attainments in their material base. Tapping on a keyboard, or scratching with an old nibbed pen, is a way of tethering thought to the physical world. And, conversely, our mental agility is a reflection of, indeed an emergence of, our manual and technological dexterity. Watching a teenager double-thumbing on tiny virtual keypads, when it comes down to it, provides both a lesson in humility and a jolt of recognition.

My 3 year old is pointing and dragging on any screen he can reach. Proficiency in this now seems to come before writing, not to mention typing (which I was taught through an optional course when a graduate trainee – one of the most useful things I did during the two years). On the other hand, books are still an essential at bedtime.

Yes, same here – they talk a lot at nursery (my 3-yr old’s, not mine) about mark-making, which they seem to understand as prior to both writing and drawing (not unreasonably). But much of his mark making is smeary fingerprints when he and his older brother get hold of my phone and play Angry Birds. Still, his brother has learnt to write pretty well and it was the same with him.

Interesting to speculate on the future of coding- I suppose it depends on the ascent and hegemony of apps, which are essentially ‘closed’ and unalterable. From this era that is now ending we were given Microsoft powered pc’s that are infinitely adjustable but complicated and confusing, to the apple era where customisation is taken away from the consumer in the name of simplicity (yet actually in order to monetize every aspect of the transaction) Something that we seem happy to stumble towards

The final examination of my degree was the last time I wrote anything longer than a few notes or a greetings card by hand. The annual Christmas card marathon is pure agony on my underworked penmanship muscles.

Precisely Worm – it’s all about apps and devices now, and the comfort of shiny (and admittedly quite good) commercial packages. No more liberating universal platform of stuff. I suppose the ideal of wholescale code literacy was always a chimera, but I cling to the belief that it would have represented an evolutionary leap for the species (albeit in the direction of the Borg)

And Brit – I had to hand-write a three and a half hour exam a few years ago. Extraordinary experience. I’d forgotton how the arm muscles warm up after an hour. Towards the end I was watching the pen like Mickey Mouse watches the brooms in Fantasia. Goes without saying it was totally illegible.