This week Toby Ferris’s mission is to boldly go where a select group of men have gone before: to help patch up the world’s oldest piece of literature, a crumbling, fragmentary poem on the fear of death…

I am struck by the vain but pleasing thought that the Anatomy of Norbiton is (not uniquely, and only temporarily) the newest thing in All World Literature. There it stands in its fragmentary state, a rickety high-rise among the myriad gleaming skyscrapers springing up as ever across the brownfield sites of civilization.

And from its windy heights I can just make out, at the opposite extreme of literary time, a familiar tumbledown clay-brick ziggurat: Gilgamesh – das Epos der Todesfurcht, the epic of the fear of death, as Rainer Maria Rilke called it. The oldest thing in All World Literature.

Here is a version of the story of Gilgamesh as told by Star Trek’s Captain Picard to a dying alien called Dathon. Picard and Dathon – to supply a little context – have no common tongue, Tamarian, Dathon’s language, being composed entirely of references to an unknown body of myth.

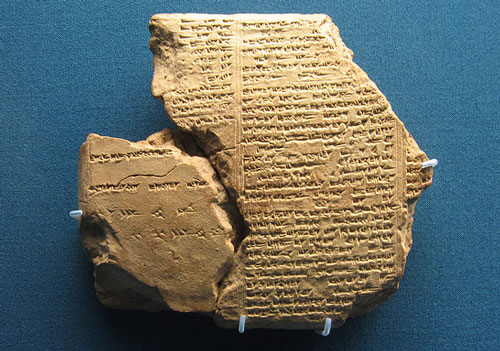

Picard’s gist of the story is necessarily compact; the epic has in fact come down to us as a vast heap of fragments of tales in languages and versions from all over the Near East. It seems to have been written down for the first time around 1800BC in Sumer by trainee scribes; most of the extant versions are in Sumerian (early tales in very fragmentary form, dating probably from the third Sumerian empire of Ur) or Akkadian – the lingua franca of the early Bronze Age in the Ancient Near East.

At some point between 1300 and 1000 BC this jumble – known, from its opening line as ‘Surpassing All Kings’ – was given proper epic shape by a Babylonian bureaucrat or priest or poet called Sîn-liqe-unninni. Under his hand, ‘Surpassing All Kings’ became ‘He who saw the deep’, the threnody of Rilke’s imagination. Enkidu ceases to be a servant of Gilgamesh and is installed instead as his boon-companion. He comes to the relief of Uruk, which had been sweltering under the yoke of its restless king (‘he tormented his subjects, he made them angry’) and his subsequent death becomes the focus for Gilgamesh’s anguished fear of mortality.

For all that it was ubiquitous during the Bronze Age, the poem’s existence was entirely forgotten until vast hoards of fragments of tablets were discovered in 1850 by George Layard and his assistant Hormuzd Rassam at Nineveh, the Assyrian capital. These tablets lay untouched in the British Museum’s archives until a self-taught Assyriologist, George Smith, turned his attention to them in the early 1870s, and the first translations of the epic began to appear.

In spite of many fresh finds in the years since, the text remains largely incomplete. It is characterised as much by lacunae as it is by words. At least 575 lines of the original are entirely missing. Much of the rest is illegible, corrupt. Scraps and versions existing in languages we can barely read – Elamite, Hurrian – are used to patch up the gaps, to support best-guesses.

Rilke considered this to be one of the poems great defining characteristics. A poem of the fear of death which was itself a fissured, crumbling fossil of the literary desert, to be read with gloves and fine brushes and a mortician’s detachment.

But it could be read differently – not as an old poem that had fallen apart, but as an ongoing reconstructive effort of the scholarship and the poetic imagination of the nineteenth and twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Rather than the gaps, we could note the sinews and skeleton of archaeology and Assyriology and philology which bind these friable, barely legible items together; and the flesh and musculature of our own poetic contexts – those supplied, for example, by Rilke and Picard.

Without these contexts, we have nothing but boxes of clay objects – the dusty oblivion which Gilgamesh so feared. There is, for example, a large body of Sumerian literature dating back to the court culture of Ur III (roughly 2100BC), similarly written down by Babylonian scribes in around 1800BC, for which we have no context at all, mythic or otherwise; and of which, therefore, we have no understanding, just some snatched bewildering gulps of Sumerian air (Darmok and Jalad at Tenagra; Shaka, when the walls fell).

Thus while much of what we have of Gilgamesh is [conjecture], much [unknown]; while there are many… … … lacunae; nevertheless there he stands, our resilient patchwork Gilgamesh, part historical, part mythical, part vehicle of our own concerns, peering over the clay brick walls of Uruk, not at us exactly, but in our general direction. Because although he cannot see us we – ghostlike, insubstantial, architects of vain towers – people his afterlife for him.

gilgamesh would be a great name for a godzilla-esque monster, and Nineveh must be one of the most magical placenames. I must get round to reading more about the poem and it’s legacies

Funny you should say that – my brother was so enthusiastic he started teaching himself Akkadian which, if nothing else, cured his enthusiasm – I, meanwhile, have been thinking I should get more organised with my Star Trek.

The Penguin translation by Andrew George is pretty good if you don’t mind the …. … .. [lacunae]

Also, I notice that Biblioklept has an interview today with someone called Stuart Kendall, mostly about Gilgamesh

http://biblioklept.org/2012/02/28/biblioklept-interviews-stuart-kendall-about-his-new-translation-of-gilgamesh-altered-states-of-consciousness-and-terrence-malick/

Astounding.

There was a loopy commenter on Appleyard’s site back in the day who kept bringing up Gilgamesh. She also told me off for spelling Edgar Allan Poe wrong. I’ve probably just done it again.