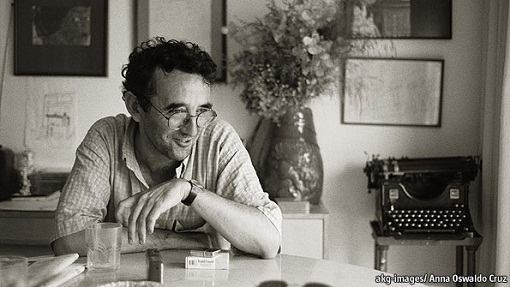

A novel entitled The Third Reich was discovered among Roberto Bolaño’s papers after his death in 2003, and has only recently been published in book form. Elberry tries to get to grips with it…

Bolaño is a vexing writer. He is generally hailed as a great genius, and even in translation he has an unmistakeable authority and poise. However, with The Third Reich as with the enormous 2666 I have the feeling that, to borrow from Bob Dylan, something is happening but I don’t know what it is.

Unlike 2666, which made no sense at all, The Third Reich has a clear, almost allegorical plot. The narrator, Udo, goes on holiday to Spain with his girlfriend. Both are about 25. They stay at a hotel Udo knows from his youth, and there he meets his teenage crush, the now-35 Frau Else, still beautiful. Udo and his girlfriend meet two dissolute Germans and they go to bars and get drunk. They befriend two seedy locals, inexplicably named the Wolf and the Lamb, and a burns-victim and (it seems) ex-soldier called El Quemado. Udo spends most of his time in his hotel room, playing a WW2 board game. He starts playing with El Quemado, who surprisingly quickly becomes adept, playing the Allies against Udo’s Axis forces. Udo is a world-class master but loses to El Quemado. The end.

The novel is written as a journal, allowing Bolaño to slip details in without explanation, as one would for a private record. The result is puzzlingly inconsequential, or apparently so (I always suspect there is some hidden order). It’s a pity the publishers try to deceive the reader, as the blurb declares this to be “Bolaño’s first new novel since the epic 2666” when in fact it was written a good decade earlier – it was merely published later, because Bolaño seems to have rejected it as juvenilia. It is, if anything, more interesting if read as a rejected first novel, especially from before the Berlin Wall came down (details about East Germany make little sense unless you know the date of composition). There is a curious journal entry for September 11, which I took to be an allusion to the attack on the World Trade Centre:

In the sky a Cessna prop plane strove to trace letters that the strong wind erased before I could make out entire words. I was gripped then by a vast melancholy that seized my belly, my spine, my bottom ribs, until I doubled over under the sunshade!

I realised in a vague way, as if I were dreaming, that the morning of September 11 was unfolding above the hotel, at the height of the Cessna’s ailerons, and that those of us who were down below that morning, the retirees leaving the hotel, the waiters sitting on the terrace watching the little plane’s manoeuvres, Frau Else hard at work, and El Quemado loafing on the beach, were in some way condemned to walk in darkness.

Only after finishing the novel, I learnt that September 11 is a Spanish holiday, and Bolaño was writing a good decade before the attack on New York (one could assemble an interesting list of such inadvertent prophecies).

The novel’s closest literary relative, in my reading, is Kazuo Ishiguro’s enormously long The Unconsoled: both are somewhat Kafka-like, in introducing some inexplicable, surreal element into an otherwise conventional narrative; both are, to my mind, not very satisfying. Like dreams, they are interesting at the time, having a sense of purpose and clarity, elusive logic; on waking they are soon forgotten. Bolaño’s book is not as irritating, in that it is much shorter than Ishiguro’s, and has an intriguing formal clarity. The hero is a West German, working for an electricity company such as Alstom; he goes from one of the most orderly countries in the world, to the famously disorganised and haphazard Spain. He recreates, and replays, the actual chaos of the Second World War, as a board game. Even with dice, such a game has structure, rules; war has none: Hitler could have chosen to use women soldiers, a football player cannot choose to openly taser his opponents. Within the framework of a game, Udo tries to understand, and to master, an overwhelming, chaotic energy – as, one might say, a power plant manipulates the energy we call electricity. He plays as the Germans; he is trying to remake history, within the game, though he is if anything an “anti-Nazi”, in his own words. Likewise at the hotel he pursues Frau Else, trying to seduce the woman he desired as a teenager.

He fails in both, here. We expect, because Else appears in the first chapter, that the book will be about a romantic seduction. Instead, she keeps him at a distance, then, inexplicably, kisses him, seeks him out, but then refuses to go beyond kissing, and in the end nothing actually happens. “Nothing actually happens” could be the book’s subtitle. But not for weakness – it seems rather a calculated effect:

As summer fades (or as the visible signs of it fade), noises begin to be heard as the Del Mar that we never suspected before: the pipes now seem empty and bigger. The regular muted sound of the elevator has been replaced by scratching and races behind the plaster of the walls. The wind that every night shakes the window frame and hinges is more powerful. The faucets of the sink squeak and shudder before releasing water. Even the smell of the hallways, perfumed with artificial lavender, breaks down more quickly and turns into a pestilent stink that causes terrible coughing fits late at night.

One can’t help noticing these coughing fits! One can’t help noticing those footsteps in the night that the rugs never manage to muffle!

But if you go out into the hallway overcome by curiosity, what do you see? Nothing.

As in Hamlet, something rotten, a pervasive unease. Even within the game, chaos intervenes, the mysterious and rather allegorical El Quemado somehow becomes an expert, and Udo’s careful planning, his knowledge and expertise, come undone and Berlin falls again. The plot is better than the novel; I was reminded somewhat of Ian McEwan – the same sense of a carefully thought-out plot, conciously-chosen “themes”, a mechanical assemblage like something from a creative writing school, with a little brutality thrown in, as a bad chef might add spices to an insipid meal. It’s not, however, the come-hither-Booker-Prize whorescript of McEwan; it has more the feeling of a genuine talent finding its way, as is proper for a first novel.

Thanks for this interesting and very astute review. Fyi the reference to September 11 in The Third Reich is to September 11 1973, the date of the overthrow of the democratically elected government of Chile by fascist military generals who bombed the La Moneda Palace in Santiago when the president Salvador Allende and members of his government were inside. Bolaño was in Santiago at the time and saw the enormous plumes of smoke that resulted from the attack. He was arrested and briefly imprisoned shortly afterwards. The subsequent horror that engulfed Chile haunted him until his death and impermeates much of his work, including The Third Reich. .

Thanks for the review Elberry, I was curious about this book after having seen it on the publisher’s release, your review has saved me from getting hold of a copy as I’m not a fan of overly ‘literary’ books