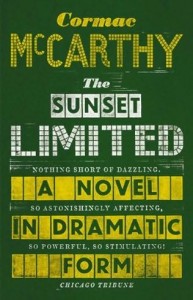

Elberry puzzles over a ‘novel in dramatic form’ from the author of No Country for Old Men and The Road…

Here is a puzzling thing. McCarthy, who is generally known for harrowing tales of bloodshed and mutilation, has written a play starring a ex-crim and a suicidal professor, sitting at a table debating the meaning of life. There are no fireside decapitations. There are no mutilations. There is no genocide. There isn’t even any wounding. There are just two characters, referred to as White and Black throughout, since the professor is white and the ex-crim black.

White has lost faith in everything, including Western civilisation, and therefore tried to jump into the path of a train. Black pulled White back and somehow they end up in Black’s flat. Then they talk. Black talks a lot of Jesus talk and White talks about how Western civilisation went up in the chimneys of Dachau.

Black is on the side of life, brotherhood, and Jesus; White is a nihilist, an educated, middle-aged suicidal nihilist. It’s not as crude as Jesus versus Dachau, though: Black believes in god, and assumes this god is Jesus Christ, but the immediacy of his belief swallows up the particularity of creed; and White doesn’t debate so much as cling stubbornly to his own lack of belief, in anything. Throughout, Black tries to keep White from rushing off to kill himself. He argues, he sympathises, he tells his own jailhouse shiv stories. There isn’t much in the way of argument or debate: it’s rather a meandering conversation, generated by two irreconcilably opposed perspectives.

On a first reading it falls far short of Blood Meridian or even the weaker No Country for Old Men. Yet it is by no means bad. At times it recalls Beckett, especially in the stark close; and the argument follows Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus, up to a point. It is all recast into McCarthy’s particular, grimly humorous manner. So Black relates his first encounter with God, a voice coming to him after he nearly beats a fellow prisoner to death:

Black: If he didnt know I was ready to listen he wouldnt of said a word.

White: He’s an opportunist.

Black: Meanin I guess that he seen somebody in a place low enough to where he ought to be ready to take a pretty big step.

White: Something like that.

Black: And you think that maybe I think that you might be in somethin like that kind of a place you own self.

White: Could be.

Black: Well I can dig that. I can dig it. Of course they is one small problem.

White: And that is.

Black: I aint God .

White: I’m glad to hear you say that.

Black: It come as a relief to me too.

The dialogue is largely plausible though it slips into something more typically apocalyptic at the close, as White thunders:

I dont believe in God. Can you understand that? Look around you man. Cant you see? The clamour and din of those in torment has to be the sound most pleasing to his ear. And I loathe these discussions. The argument of the village atheist whose single passion is to revile endlessly that which he denies the existence of in the first place. Your fellowship is a fellowship of pain and nothing more. And if that pain were actually collective instead of simply reiterative then the sheer weight of it would drag the world from the walls of the universe and send it crashing and burning through whatever night it might yet be capable of engendering until it was not even ash.

Against this, Black has just his basic decency and his stubborn good humour. He seems to be somewhere between Kierkegaard’s Knight of Infinite Resignation, and the Knight of Faith, and so (in Kierkegaard’s terminology) a stage or two beyond White. He tries to persuade White as much by his presence and example as by his words, but to little avail. White’s despair seems fundamentally immovable, and at the end he leaves, to what fate we are not informed.

The play reads like an experiment, a working-out of ideas. It suffers in comparison to the novels: McCarthy is especially good at laconic dialogue, baroquely descriptive prose, and weird situations, and here he relies wholly on extended conversation and philosophical debate. The debate covers no new ground, inevitably. White gets to the point of Camus’ lucid despair but no further; he lacks the cojones for Sisyphean scorn, or pride.

The energy of the play isn’t so much in the debate, as in the characters. Both are driven by an original despair. Black has surpassed this despair, and perhaps to justify his own redemption, he seeks to redeem others. He isn’t entirely at ease with himself, but seems to have found a scarred equanimity, the Knight of Infinite Resignation. White is simply bitter and clever, though I came to feel something of Black’s compassion for him, in his bitterness.

If Black seems atypical of McCarthy – an altruistic, noble character – his failure is true to McCarthy’s fairly bleak view of things. After White leaves, Black appeals to his god:

Black: I dont understand what you sent me down there for. I dont understand it. If you wanted me to help him how come you didnt give me the words? You give em to him. What about me?

Black is, at this point, addressing the only audience left – God. Since this god is invisible, the reader is persuaded into the auditor’s role. We are invited to pass judgement – to decide if Black is crazy, or an inspired man of God. McCarthy won’t push it too far, there is as usual no hint of his preference, just as we don’t know if White will commit suicide after leaving, or if Black’s words and example will have their effect. The duality, of good and evil, or meaning and absurdity, is to be found as far back as Blood Meridian, where the Judge embodies evil, and the Kid is, if not good, then at least human, not wholly given to evil.

McCarthy refuses to rig the game in favour of the good; in this world it is enough that goodness exists, that, to take an example from Shakespeare, a Cordelia could even exist. If goodness usually fails, it seems nonetheless indestructible. In The Sunset Limited I believe McCarthy is suggesting, not that a good man can persuade a man from suicide, but that it is remarkable anyone should try, that Black’s compassion is itself grounds for optimism – totally regardless of the outcome. Failure does not negate the attempt. There are, in any case, no happy endings.

A very well written review! Thanks Elberry – Sounds like this one isn’t for me though – I loved All The Pretty Horses, and The Road was ok if so purposefully miserable that it became sort of grotesquely comic. This one sounds like hipster angst a la Murakami etc, the kind of thing to be seen reading with furrowed brow in your local alternative independent coffee house

i think my copy of All the Pretty Horses was originally a freebie with some men’s magazine, the kind of rag middle managers read so they can feel less like middle managers.

I remember getting a copy of James Ellroy’s The Big Nowhere (which I subsequently loved more than nearly any book I’ve ever read) as a freebie off the front of a GQ.

i’m a big fan of these incongruous favourites, you appreciate them more when you think you probably shouldn’t.